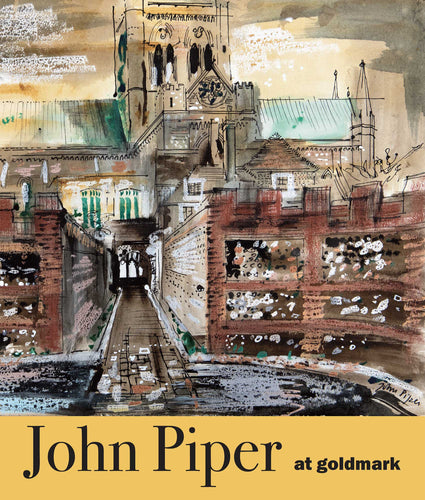

Tradition and modernity converge in mysterious ways in Piper’s greatest work in print.

John Piper’s return to architectural painting after years of abstract flirtation was seen by fellow abstract artists as a kind of apostasy. But in the Retrospect, Piper’s magnum opus in print, he proved that the contemporary and the traditional could go hand in hand, with surprising – and moving – results. n alarmingly stark photograph introduces us to John Piper in his slim 1944 Penguin Modern Painters volume. Though Piper was 40 by the time it was published, in the photograph he must only be in his mid-20s, his hair already greying, his gaunt features so pronounced that his eyes have disappeared in pools of black into a profile sharp as a knife. Piper was photographed many times in the nearly 50 more years he lived and worked, but he always retained that almost archaic, Gothic narrowness. Like the architecture he loved, there was a sense of fixed character about him, that no amount of aging or weathering, of fat or thin, could mask or obliterate.

Piper was fascinated, all his life, by the presence of the past in all things, whether they had been made by man or nature, and by the mechanism of decay. It is perhaps what fascinated him about the camera, and the reason for his own discomfort at being photographed, when his theme came rather close to home. Certainly it is an attitude that lies at the heart of the Retrospect of Churches, his greatest work in print: 24 lithographic portraits of English and Welsh churches, commissioned in the autumn of 1963 and printed a year later.

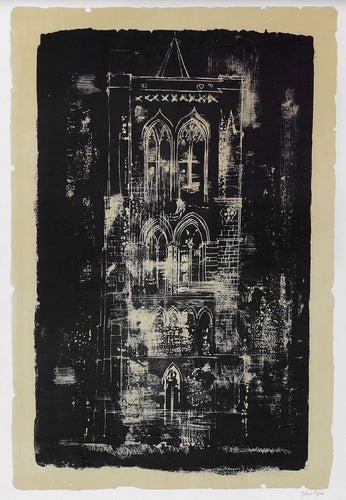

Piper’s title assures us that we are looking back, and though these prints were made nearly 20 years after the war, an eerie wartime smoke is still in the air in Piper’s black wash. The war, of course, had brought Piper’s central theme to prominence: the easy destruction of hundred-year buildings, the collapse, architecturally and spiritually, of European civilisation. St Nicholas’ church in Liverpool had been one such bombing victim: stained by dockland pollutants, it rises here like a vast and charry obelisk into the sky. In this ‘retrospect’ – neither country tour nor greatest hits, but memory consecrated in observation – I’m reminded of Charles Ryder’s return to the Flyte family home in Brideshead Revisited as a wartime captain, the former played by Jeremy Irons, the latter by Castle Howard in the 1981 Granada adaptation of Evelyn Waugh’s novel that has assumed classic status of its own. Brideshead has fallen to the soldiery, but in the chapel, the peculiarly gaudy creation built by Lord Marchmain for his wife, the interior that had once seemed ludicrous to Ryder’s artistic sensibilities shines as bright as ever, the lamp in the sanctuary lit once more in preparation for a midnight mass.

When Waugh was petitioned by Hollywood execs at MGM for permission to produce a film of the book, he replied stressing the importance of Brideshead’s symbolic architecture, and its importance to Ryder’s unspoken conversion at the story’s end, his affair with Lord Marchmain’s daughter, Julia, dissolved at her request. ‘He has realised that the way they were going was not the way ordained for them,’ Waugh writes, ‘and that the physical dissolution of the house of Brideshead has in fact been a spiritual regeneration.’ Physical dissolution as spiritual regeneration: that sounds like Piper to me.

John Piper and Charles Ryder are of course starkly contrasting characters, exact contemporaries yet two sides almost of the same coin. Charles, a stand in for Waugh who began his own career as an art critic, relents to Catholicism after a life of agnostic cynicism. Piper, it seemed, experienced the opposite, and by the end of his life had virtually renounced the Anglican Church, if not his private faith. ‘I know nothing will redeem me’, he said, ambiguously, to the critic Peter Fuller in his last years: redemption from believing, or from abandoning, we’re left unsure.

Ryder’s description of his student rooms at Oxford covers the sort of influences an aspiring artist of the 1920s might have been nourished by: an Omega Workshops screen by Roger Fry, purchased after the Bloomsbury outfit had closed down in 1919; a McKnight- Kauffer poster; Rhyme Sheets from the Poetry Bookshop; and a reproduction of Van Gogh’s tortured sunflowers. But it's not long before Charles denounces modern art as ‘Great Bosh’, his changing tastes symbolising a spiritual awakening that will eventually eclipse aesthetic concerns. The Omega screen is soon consigned to the cupboard under the stairs.

Volumes of Highway and Byways, with architectural illustrations by F.L Griggs, were for Piper what Georgian poetry and Bloomsbury thoery were for Ryder, before Piper’s own embrace of ‘Great Bosh’ in the 1930s when he turned to tempered European abstraction. Unlike Ryder, he never abandoned his student enthusiasms, nor regretted his flirtations with modernism. But the urgency of Picasso’s Guernica, as Piper’s wife Myfanwy recalled, ‘acted upon us like rape just when we had settled for the Mondrian cloister’. Piper was soon looking for a way that might bridge the two worlds of tradition and modernity he now fell between. ‘It will be a good thing’ he wrote, ‘to get back to the tree in the field that everybody is working for.’

There is an echo here of Ryder, his room drowning in a jungle of daffodils, Sebastian’s apology for drunkenly spoiling his room, finding even the Van Gogh on the wall paling in comparison to the real thing. But as far as Ben Nicholson and other fellow abstract artists were concerned, Piper’s return to tradition, to musty architecture and ‘the tree in the field’, was a kind of apostasy.

Ryder too turns to painting buildings. His search for something more profound, spiritual, earnest in abandoned and decaying Christian missionary outposts in Latin America remarkably parallels this suite of prints. Ryder’s muscly new pictures shock his public, but the perceptive Anthony Blanche knows his heart is not in it: he sees only ‘charm again, my dear, simple, creamy English charm, playing tigers.’

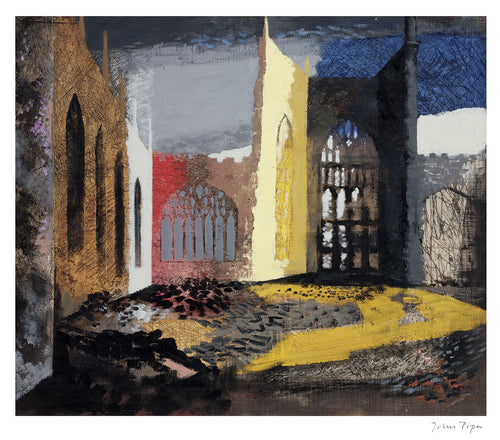

John Piper would receive similar criticism as he turned his attentions to the crumbling faces of English churches and stately homes. But in the Retrospect, he would prove that a contemporary sensibility and vivid sense of form and colour could reveal life at the heart of the must unlikely of relics.

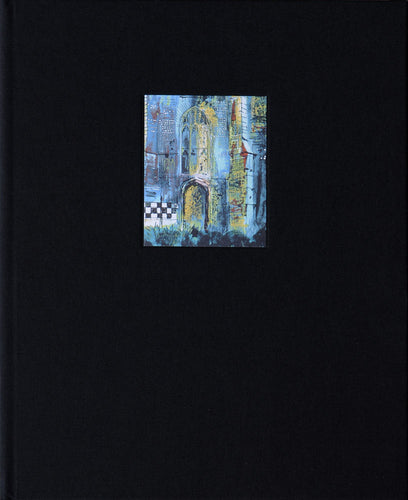

Printmaking, John Piper often said, should look easy, but it rarely is. The studio quickly accumulates detritus as iterations of prints are worked and reworked and the process threatens to take over itself, becoming almost self-generating. The feathered, deckled edges of the finished product, on thick, clean paper, gives little hint of the ink, sweat and toil that produced it. So we are fortunate that two archives – one of Piper’s home photographs, close on 6,000 of them held at the Tate, and the other comprising original studies Piper brought to his lithographer Stanley Jones, now at the Goldmark Gallery – let us go beyond those margins to see how many of these prints were made.

‘My ambition’, Piper said of the Retrospect, ‘was to make the prints look frightfully casual...This is very difficult, as printing is a very deliberate and calculated thing and you have to wait days or even weeks and be very ingenious to appear spontaneous.’ It’s an odd phrase, because in spite of the bravura of brushed, scratched and mottled ink on these plates, there is a precise, haunting spareness to the series that seems anything but casual. You feel it in the ghostly elevation of the church at Redenhall or St Anne’s in Limehouse, in Lewknor in Oxfordshire, pieced out in a slim black line and cool blue mantle, with textures from rubbed wood and stone, grasses and brickwork picked out in white with gum arabic. The series represents an unusual choice of churches, as David Fraser Jenkins points out: not Piper’s favourites, but a selection from Norman to Victorian marking a geographical shift to the midlands and the fens, to Northamptonshire, Lincolnshire, and our own Rutland, all newly accessible via the M1 motorway that had opened in 1959.

Piper’s perspectives vary too from external views to interior oddities, sometimes so particular that their surroundings have shimmered and dissolved away, or are cloaked in darkness. Vangelder’s monument to Mary, Duchess of Montagu, in Warkton, Northamptonshire is virtually illegible compared to the 1775 white marble carving, cast here by Piper in a strange, piercing jigsaw of shadow and light. St Kew, in Cornwall, is lost amid a fiery orange flourish of overgrowth. And with Piper’s original beside it, the beakhead carvings on the extraordinary Norman archway in Tickencote that were ornamented in pale grey and delicate peach in the gouache have been literally electrified by a suspended lamp, illuminating the lemon-yellow background of the lithograph. Few of the churches and their features are shown in context, but are self-contained, falling somewhere between enigmatic portraits and characterless set designs. Exceptions include the city churches – Nicholas Hawksmoor’s spire in Spitalfields, G.E. Street’s churches at Paddington and Westminster, and the 18th-century church in Easton, on the Dorset peninsula of Portland. The area was a favourite of Thomas Hardy’s, carved, as he described it, ‘by Time out of a single stone’. Piper’s research photographs show the church and the ornate gravestones in the cemetery drowning in a sea of cow parsley and errant grasses, like abandoned boulders in the nearby quarry.

The overwhelming effect of turning from one print to another is of abiding impressions that have survived the forgetting fog of a dream: memories of the past, as Piper’s wife Myfanwy beautifully put it, that ‘like wasp stings accumulating in the blood, accumulate in the mind and the imagination.’

‘He came like he was going to battle,’ Fernand Mourlot remembered of Picasso, arriving at his Paris workshop to make prints. Though less commandeering, John Piper came prepared to the process of lithography when he began working with Stanley Jones. He had already seen and worked on the other side of the business with the traditional Curwen Press, who had editioned the collaborative series of Contemporary Lithographs Ltd in the late 1930s. The print market was then in a catastrophic slump, with a collapsed American market and war looming on the horizon. By the time of the Retrospect, 30 years later and half a lifetime on for Piper, everything had changed. The gallerist Robert Erskine had helped reignite interest in original artists’ prints with his publishing venture at St George’s gallery in the second half of the 1950s. It was Erskine who had found Stanley Jones and proffered his services to Curwen, keen on establishing their own dedicated lithography studio. Piper and Stanley had even already met, as respective tutor and star student at the Slade.

In our age of creative liberation and multidisciplinary art, it is almost impossible to imagine the landscape for printmaking back then, when age-old assumptions and rules still remained stiffly in place. Only a year after the Retrospect was printed these would come to a head, with the brouhaha that followed the exhibition of screenprints printed by Chris and Rose Prater at Kelpra Studio at the Paris Biennale. The French officials bluntly refused to catalogue any print incorporating photographic materials or processes as ‘original’ – even when that material was the artist’s own. Kelpra had the last laugh in the end, when, in spite of the controversy caused by the upstart Brits, Patrick Caulfield’s Ruins, printed by Kelpra, won the unofficial Prix des Jeunes Artistes. Piper might have smiled to see that he was not the only artist combining contemporary technique with antiquated subject matter.

Far from being mired in the past, Piper’s Retrospect represented an early attempt at weaponizing modern methods. Though it seems rather quaint today, his use of photography in the façade-like portrait of the church at Llangloffan was particularly daring at the time, and raised eyebrows even at Curwen, then still firmly divided between the established church of the Press and Stanley’s nascent, nonconforming Studio. But the layering of photography, stone rubbings and subtle colour, and the collaged relocation of the tree in the upper righthand corner, seemed quite appropriate for this Victorian Baptist chapel, set in the spartan North Welsh countryside and inscribed with dates alerting us to its own history of architectural amendments: 1706, 1749, 1791, 1862. The chapel lay not far from the remote coastal stretch at Garn Fawr where, in the autumn of 1962, the Pipers had purchased a small cottage of the same name. The combined severity and majesty of the place, its isolation, its bleakness and its colour in the margins – wild flowers, pebbles and coastal scree – were surely a direct influence on the Retrospect, where churches loom like rocky peaks, or like spiritual lighthouses in rough seas.

Across its 24 images, Piper’s Retrospect became almost an alphabet of techniques and approaches, with Mourlot’s recent book reproducing Picasso’s lithographs his guide. Together with Stanley Jones, they would pore over the Mourlot illustrations and try to reverse engineer the Spaniard’s virtuoso methods. More than just a challenge of matching all that Picasso could do, however, there was an opportunity also to find an equivalent use for the substantial arsenal of techniques Piper himself had developed and leant on in his abstract paintings, and the ephemeral material he gathered about him: collage, wax-resist washes, incising through gouache; photographs, sketches, endpapers.

Failures – marbling transfer paper in the bath produced only slop – were outnumbered by often unexpected successes. Some of the very first prints Piper trialled with Jones at Curwen were interpretations of abstract seascape collages, the normal process reversed by the backwards logic of printmaking. Instead of laying down his wash first, and moving gouached discs around the page, this time shapes were glued to the stone with gum Arabic and lithographic washes laid on top, leaving the collaged patches unscathed. Similar approaches produced the highly abstracted vision of S.S. Teulon’s unusually patterned brick columns in Leckhampstead, a study in black and white contrasts fortified with stripes of blood red.

The revisionary nature of printmaking, in which prints are made by an accumulation of errors, edits and ‘happy accidents’, suited the character of the churches themselves, many of which had suffered damage through the years and been rebuilt in part, so that Norman and Early English carvings often shouldered 17th and 18th century additions. In the medium of lithography, Piper even had at hand the materials that church masons had worked with themselves: stone blocks and metal plates on which he could enact a kind of weathering such as the churches had survived over centuries of abuse, scraping through the thick, oily ‘tusche’ with which a lithographer draws or paints and occasionally deliberately ‘mishandling’ colour blocks and their registery. Reproducing the intricate Norman carvings at the south porch of Malmesbury, Piper scored through thick gouache studies with a biro before taking rubbings from this first study and repeating the process, like a medieval sculptor chipping away at the stone. At least four original sketches exist for this image, each in the sumptuously alive terracotta red in which the print was finally printed.

Piper’s camera, held low and pointed high, remains the unsung collaborator of this series. Piper was a practiced photographer, from his days illustrating Shell Guides and working for the Architect’s Journal. There is something Hitchcockian in the way he has isolated these buildings, and made them stick up from the landscape like overlarge headstones, as if marking their own demise. You only have to imagine Piper in a dark room, handling negatives, to see how the tenebrous quality of photographic film might have affected his art, especially the reversed, spectral white on black of Gedney in Lincolnshire or Christ Church in Spitalfields. Photography, Piper told the art historian Pat Gilmour, ‘allows the gloom of the atmosphere’: ‘I photograph from paintings’, he said, meaning that he would photograph from trialled ideas or from something he had already discovered in the place, hoping that the camera might return a ‘back reading’ which he could develop.

But the real fascination of seeing Piper’s photographs next to his prints is in seeing how he capitalised on what must have been the fortuitous effects of photography, as well as those he had intended. In views of Norman archways, shadows in doorways that would otherwise have been easily penetrable are turned, through overexposure, to blackened maws. The deep porches at Gaddesby, Kilpeck, and Malmesbury at first seem an artistic decision to enforce the draw of the entrance way; but when you see Piper’s photographs, the parallels are unmistakable. In his photographs of the church interior at Inglesham (built in the 13th century, and long a favourite of John Betjeman), white lines and light leaks have added to the material contrasts of wood and stone, suggestions of pattern that Piper might have adopted when he chose to use rubbings of wood grain in the print. The camera seems always to be anticipating, suggesting, inventing details and motivating decisions: the deliberate underexposure at St Mary and All Saints in Fotheringhay, for example, that has turned it into Hammer Horror nightmare backdrop. And in Piper’s portrait of Grinling Gibbon’s monument at Exton, just a few miles from the Goldmark Gallery, the otherwise milkwhite marble of Gibbon’s 1683 carving is suffocated in shadow. Visiting the church, you find it so chock full of stone carvings dating back some 700 years to the parish’s foundation that it appears rather like a sculptor’s garret. But Piper’s photography, and the Retrospect print, swaddled in black and cooled with blue overprinting, remind us of the intimacy of the monument, designed for the Viscount Campden who tragically outlived three of his four wives and several of his nineteen children.

Retrospection and revisitation: both Waugh’s book and Piper’s portfolio deal with our two-way relationship with time, forever journeying back into history and memory and finding ourselves shaped by what has been. Piper’s Retrospect is not just a trip down memory lane, ‘the distillation of half a century’s looking at churches’, as John Betjeman’s foreword described it, nor a memoir of techniques, processes, methods, moods. Like the photographs he took, with their illusion of timelessness, Piper knew that he was making objects that, from the moment of their creation, were cemented in the past. That the churches he had chosen to memorialise would change again, and these images, years from now, might become unintelligible as land and ivy reclaimed stonework, or as human idiocy blew it to bits. It is the past’s capacity to reach into the present and touch, move us, that Piper gives us in these prints; the same capacity that stands at the heart of the Christian faith, the Catholic sense that Charles Ryder experiences of Christ’s sacrifice as both a historical event and moment out of time, eternally felt. Piper’s faith was of another denomination, and another kind of ambiguity. But his trust in that essential truth, and the beauty it had motivated, remains in his work. In the corner of the preliminary collage study of Llan-y-Blodwell’s interior, an eccentric patchwork of floral ornament and geometric celebration, Piper pencilled three lines from the litany of the Common Book of Prayer: ‘From lightning and tempest From earthquake and fire Good Lord deliver us’