Ceri Richards’ post-war period was a time of reflection, painting the interior scenes of his London studio and trying his hand at painted ceramics. But the discovery of a major new theme – and a new medium in which to explore it – would produce a flurry of fascinating, mythically charged ceramic works that have never been seen before – until now.

Ceri Richards, Vase with Handles, hand-painted ceramic

In the years immediately after the Second World War, two men – Ceri Richards and Pablo Picasso – turned to ceramics in search of new avenues of form and expression. Richards, whose collection of Picasso material was one of the largest in the country, has often (and sometimes unfairly) been seen as a Picasso follower. But in this one instance perhaps, two fortuitous events separated by mere months, it seemed simultaneous curiosity brought their paths together briefly in convergence.

Ceri Richards, Plate, Coster Woman, hand-painted ceramic

Much is known and has been detailed of Picasso’s discovery of this new medium in the Madoura workshop in Vallauris, in the south of France, where he lived from 1948-1955. How he had arrived in mid-summer of 1946 while holidaying at Golfe Juan, an entourage in tow, ‘having nothing very urgent to do’ as Georges Ramié, co-founder of the pottery with his wife Suzanne, remembered it, and poked his head through the door. He had been inspired to visit by an exhibition of local potters’ wares. Invited to take a workshop bench, he moulded three figures by hand, two bulls and a faun, before leaving. A year later he was back with a box filled with sketches, his imagination fired by the possibilities.

Ceri Richards, Vase, Pearly King, Coster Woman, hand-painted ceramic

In all, Picasso made over 600 ceramic designs in a twenty-year period that stretched into his twilight years, and well beyond his last in Vallauris in 1955. His last terracotta plaques were editioned just months before Ceri Richards’ own death in 1971, bringing a period of typically virile and fruitful exploration to a close. But of Richards’ contemporary pots, virtually nothing is known except their private, investigative nature. Only a single example of his painted ceramics escaped into public hands, apparently through his Marlborough dealers in 1970 to the V&A: an earthenware dish with a portrait of a costerwoman at its centre, thoroughly Picasso in its vigorous rearrangement of form, thoroughly Richards in its florid abundance, where a feathered hat seems to burst into bloom.

Ceri Richards, The Piano Player, gouache, 1948

A similar, smaller dish joins several other pieces at the Goldmark Gallery this summer, direct from Richards’ family. Of John Erland, in whose workshop the pots were made around 1948-9 (when the larger amphora-style vase has been signed), we know very little, other than he produced earthenware vessels for design commissions: some tableware, and vases for wicker lamps. The pots themselves were apparently brought straight into the Richards’ family home in Wandsworth Common, where they had moved in 1945, finding the building in lopsided disarray after the London bombing raids.

Ceri Richards, Coffee Pot, hand-painted ceramic

The war for Richards had been disquieting, if comparatively uneventful. 1939 had entailed a strenuous and unproductive year of labour in the fields, followed by fire-watch for the Home Guard, looking to the skies for incoming aerial assaults and dousing firebombs with buckets of sand. Industrious periods of painting in between his duties built toward the extraordinary, sometimes orgiastic explosions of form and colour that characterise a nature cycle series inspired by Dylan Thomas’ ‘force that through the green fuse drives the flower’. But the end of the conflict called for a return to domestic introspection. In 1945 the V&A jointly exhibited Picasso and Matisse, to national outcries, returning Richards to the two major French painters who influenced his career. As Matisse had done during the war, Ceri Richards looked to the living rooms around him with paintings of piano players, invariably portraits of women, surrounded as he was by his wife and young daughters. At some point, he must have been presented with the opportunity to make the pots that he had painted into many of these pictures, sitting on tabletops and cabinets in ornate Matisse-like interiors. There must have been a draw too to the idea of depicting space he was himself creating, painting the rooms he was filling with his own work: a form of creativity that was both reflective and generative at the same time. A Dragon pot, a recurring character in several interior paintings and sketches from 1949-50, Richards had decorated himself, likely at the same time as these ceramic pieces.

The Rape of the Sabine Women (detail), Peter Paul Rubens, oil on oak, c.1635, The National Gallery

Richards liked a theme, a subject: something to work his way into, like a worm into wood, until he found a common core. These pots are no different. Returning are the wartime costers and flower women in ornate dress, as if their wares were actually blossoming on their bonnets, and the Pearly Cockney Kings and Queens of the East End, mother-of-pearl buttons and sequins sewn into the seams of trousers and dresses. Like his later drawings of beekeepers, what might have begun as an exercise in pure decorative design, moulding a matrix of intersecting patterns into looping forms, ended up producing portraits that were strangely poetic, almost Shakespearean. He had first noticed them at the Hampstead Heath fairground, where their extravagant outfits and mannerisms had caught his eye, seeming to him faintly primitive and magical.

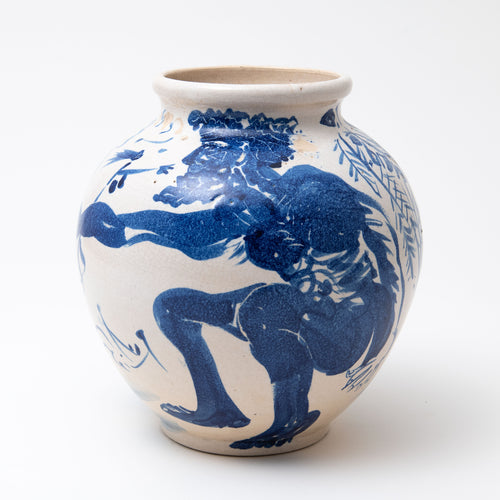

Ceri Richards, Greek Vase (detail), hand-painted ceramic

A more prominent new theme adorns two of the larger vases in this collection, one that was to become the defining theme of this post-war period: the legend of the Rape of the Sabines. This classical episode, revisited in the ancient literature by Plutarch, Livy and Ovid and long the subject of Western painting, produced a prolific outpouring of paintings that quickly culminated in an exhibition at the Redfern gallery in 1948. Like his contemporary paintings on the theme of the Lion Hunt, via Rubens and Delacroix, it presented a subject that allowed deep engagement with his preferred themes: of glory and sorrow, splendour and violence, life and death in a rapturous cycle of change.

Ceri Richards, Greek Vase (detail), hand-painted ceramic

The story itself is of course one of great violence, made respectable by Renaissance adaptation: not ‘rape’ in the explicit modern meaning of the word (though the episode was certainly eroticised by some), but in the archaic sense of a ferocious abduction en masse as often happened in times of war and siege. Romulus, founder of Rome, sees the future of his new city in jeopardy: there are not enough Roman women to sustain and grow his population. He announces a grand festival of games and invites guests from the nearby native tribes to the east. As the festival commences, he gives a signal to his men to seize the attending wives of his guests. In the inevitable warring that breaks out, the Sabine women eventually hurl themselves between the Roman and Italic lines, declaring they would rather die than be widowed or orphaned. The two sides are reconciled, and the Sabine peoples settled on the Capitoline Hill.

Ceri Richards, Greek Vase (detail), hand-painted ceramic

Rubens’ 1635 rendition of the story remains the most famous example of the myth in painting. Hanging in the National Gallery collection, it was certainly known to Richards – though as Mel Gooding has pointed out, reproductions of the painting, of Rubens’ drawings, and of Delacroix’s paintings too, all of which Richards had been reading and engaging around this time, would all have been monochrome. The effect was that the graphic element of the original is heightened, and its lurching internal directions. There are hands and arms everywhere, clasping, pulling, gripping, tugging, praying. This churning sea of movement which fixated Richards, between individual figures and the broader composition, he now had the chance to reproduce in a three dimensional form. The rotation of the wheel presented him with a canvas in the round: the image must cross its surface. Either you or it have to move round its axis to see the action, man and woman frozen in a moment of fierce embrace.

Like Rubens, who plays with historicity, dressing his women in contemporary garb and his men in ancient costume, Richards toys with historic modes too. His cobalt blue and white design mimics Chinese ceramics, but the iconography of flattened figures moving round the pot is far closer to Grecian pottery. Imitation, genre and style are all being played with here.

The Sabine myth is not unusual in Roman literature for its combination of festivity and violence, destruction and procreation, but it’s not hard to see why the story would have resonated with Richards. Ultimately it was what we would call a foundation myth: a story tied directly to the identity of a people or nation, centred on the concept of lineage and miraculous survival. Its purpose may have been to provide a retroactive model for more recent assimilations of peoples into Rome’s orbit as it expanded its boundaries. But it gains in poignancy in Richards’ hands with the proximity of the recent war: the very establishment of Vallauris as an area of renowned pottery, Georges Ramié reminds us, was due to the displacement of artisans in France and across Europe and their collective return in its aftermath.

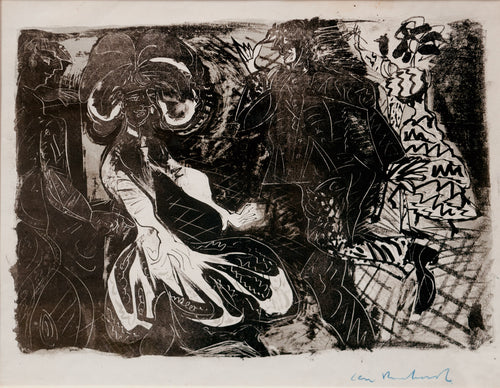

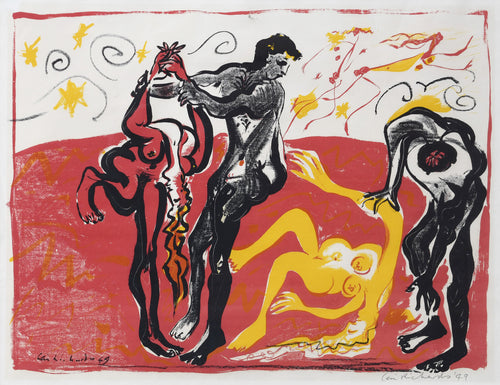

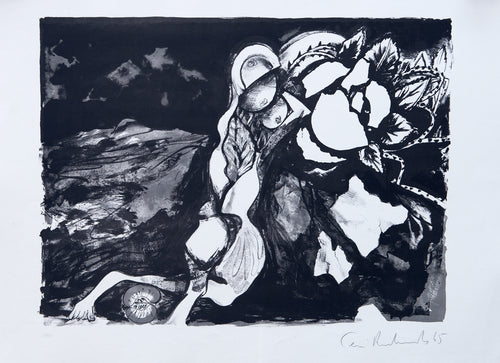

Ceri Richards, The Sabine Theme, lithograph, ed 50, 1949

For years a 1949 lithograph of the Rape of the Sabines theme hung in our family bathroom. Ignorant of the subject matter, I had always naively assumed it was a picture of dancers or acrobats practising: the men seemed to me to be holding the women steady as they extended, lengthened and seems to somersault their bodies. In my head, their agency had been reversed: this was an image about the movement and form of the female body; the men were simply stabilising pillars. I’m sure this is no accident on Richards’ behalf. Here he innovatively turns the motif of the lamenting women and their perspective quite literally on their heads. But then, how typical of Richards to have fused the old world with the Baroque, and then with the modern, inviting in the Modernist fascination with the circus, the fairground, the dangerous, primitive ecstasy of the dance – as of course the original story does, when celebratory games descend into war.

Ceri Richards, Vase with Handles, hand-painted ceramic

Richards was essentially no less interested in the erotic than Picasso. Sex, often in the transformative symbol of the female figure flowering open, like an O’Keefe painting, is a constant in Richards’ pictorial mythology, whose central story is one of cycles of love and death. But as keenly as he saw the thematic balance of creation and destruction, sex and violence, tragedy and ecstasy, and painted it all in even these most domestic pieces, rarely is there the hoarse and hairy lustiness of Picasso in his work. Where Picasso could not help but fit the hugging curves of the female body to the swell, narrow, and swell of a jug form, so that your hand clasps round her neck and breasts, Richards has his (no less busty) figure float around it, as if swimming in lilac ornamentation. His was always a gentler order of feeling.