Looking back towards the end of his long life, the Neo-Romantic artist John Piper (1903–92) shared his memories of the Second World War. At a time when Britain was under attack and travel abroad strictly limited, Piper recalled how ‘roots became something to be nurtured and clung to instead of destroyed.’ These conditions proved productive for Piper, and for many in the loose artistic grouping we now call the Neo-Romantics. This was because, as Piper put it: ‘They led to another exploration: beauty spots, rivers, mountains, waterfalls, gorges, ruins and cliffs’.

John Allen photographed in his London studio by Jay Goldmark

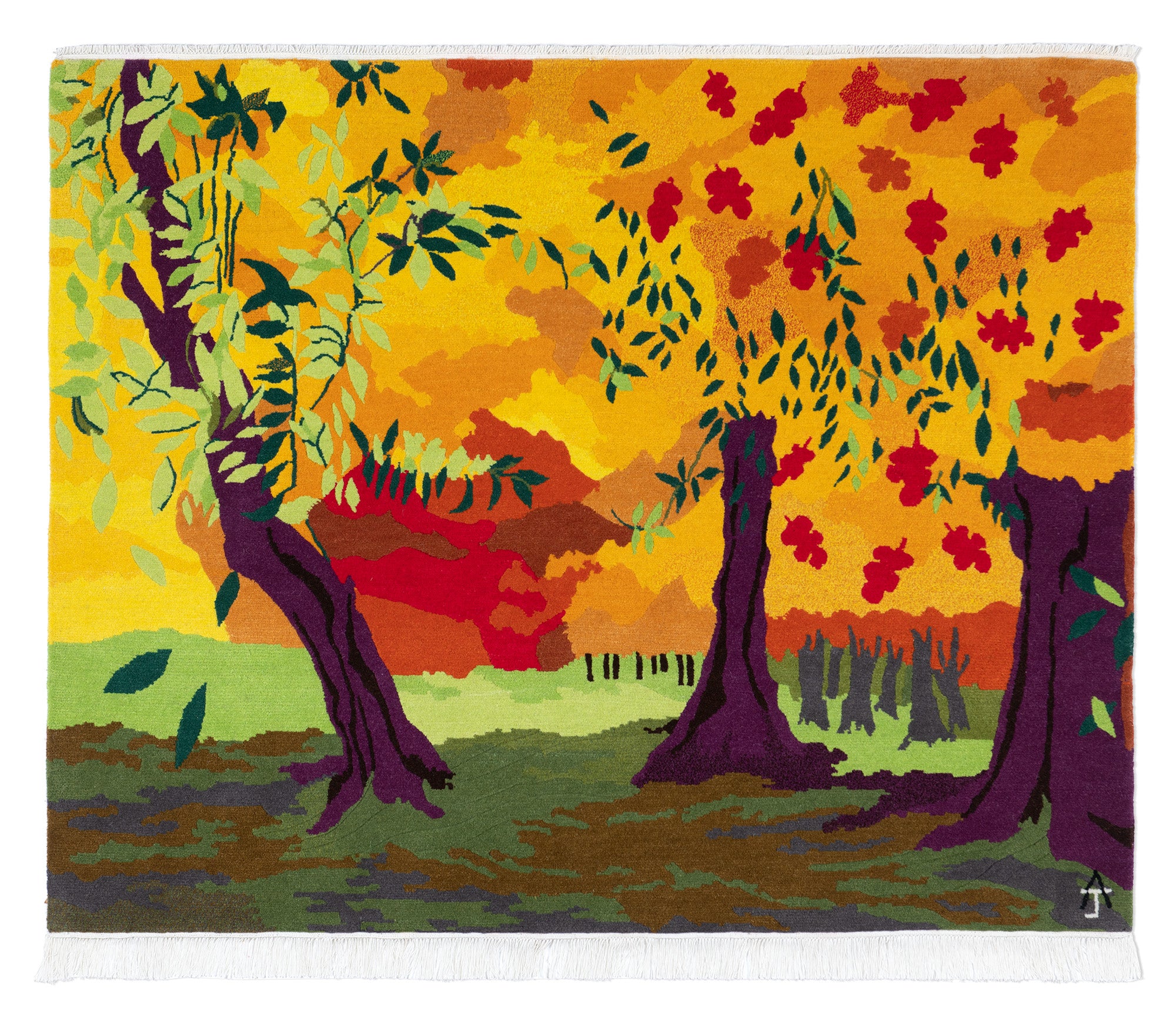

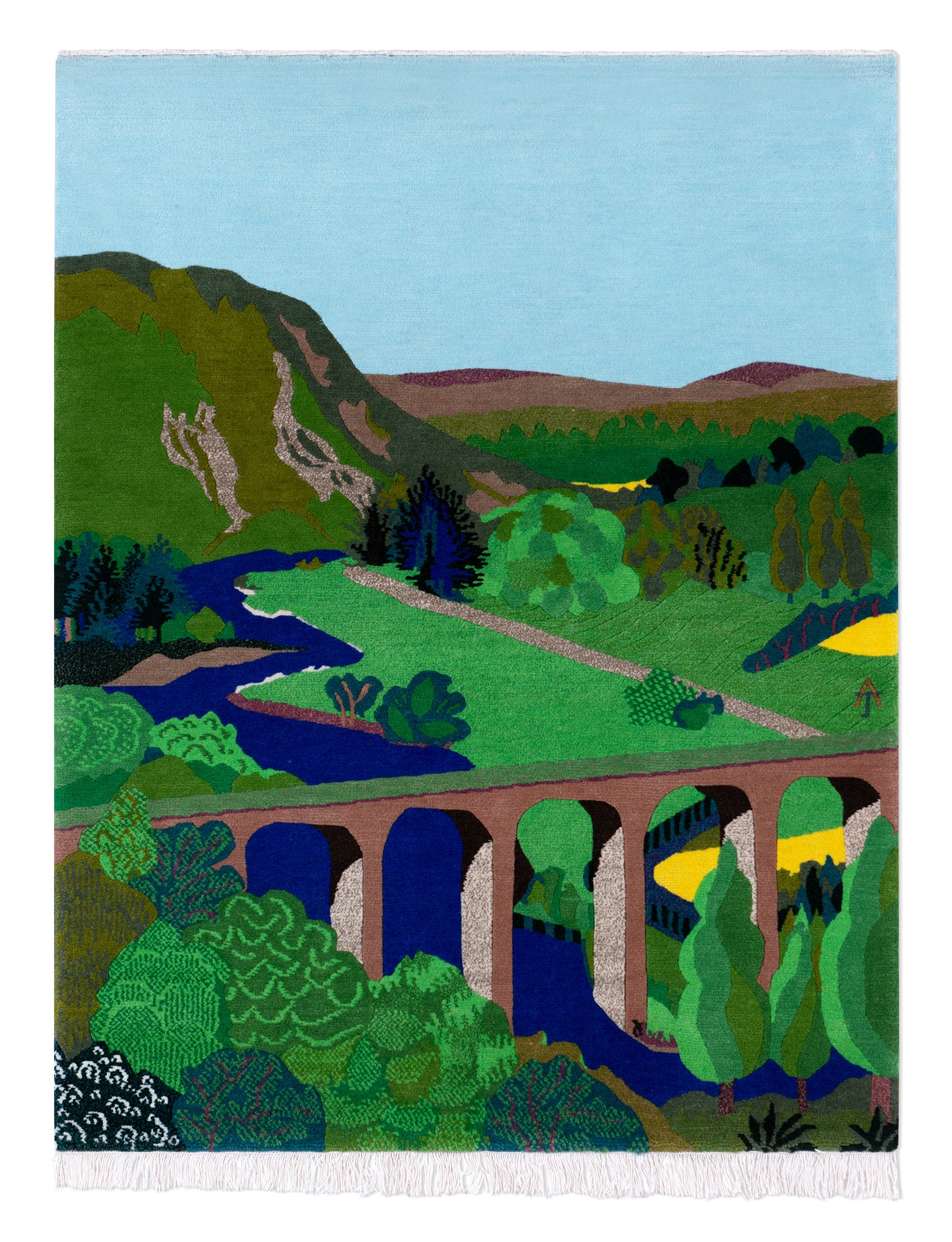

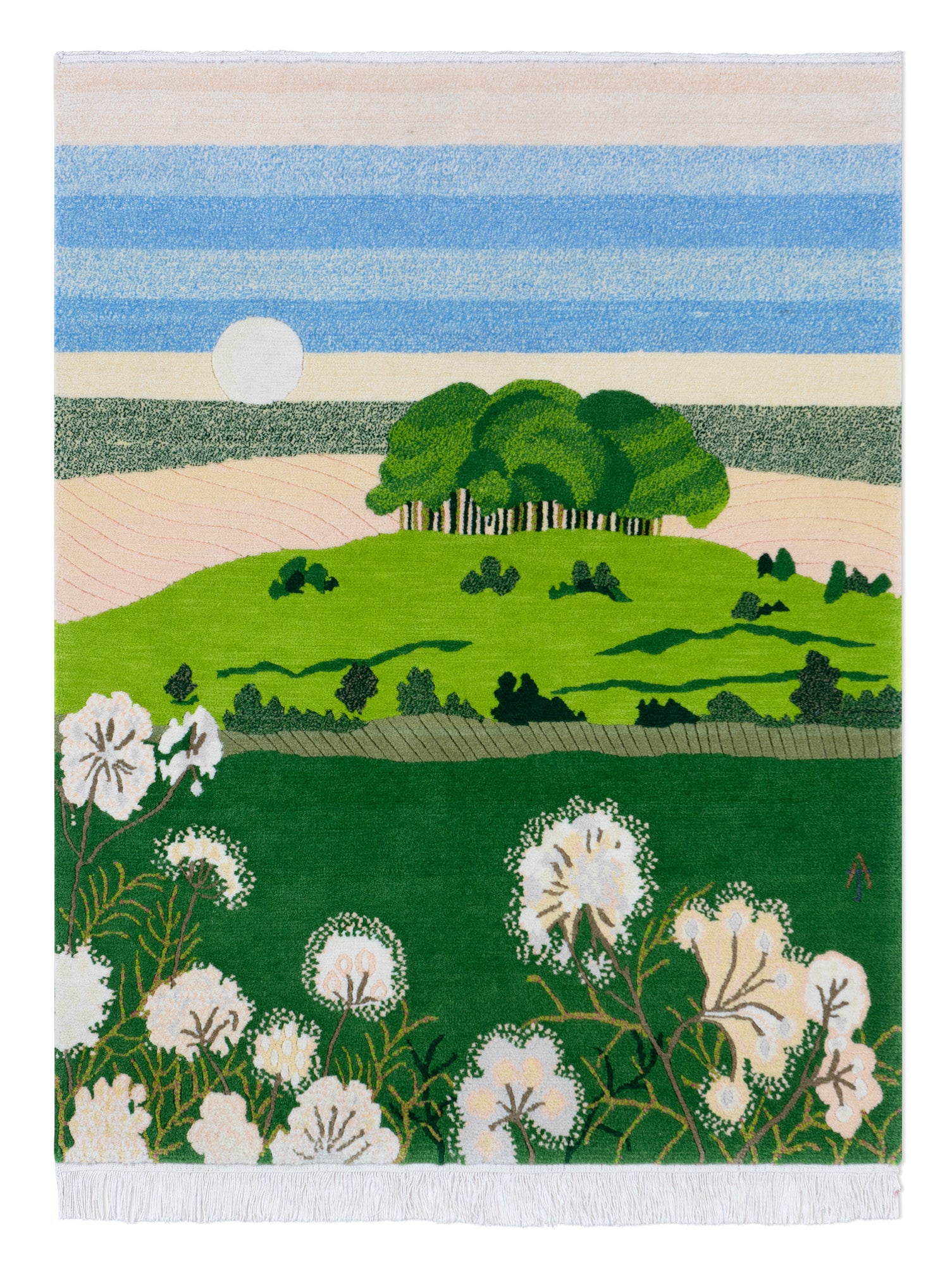

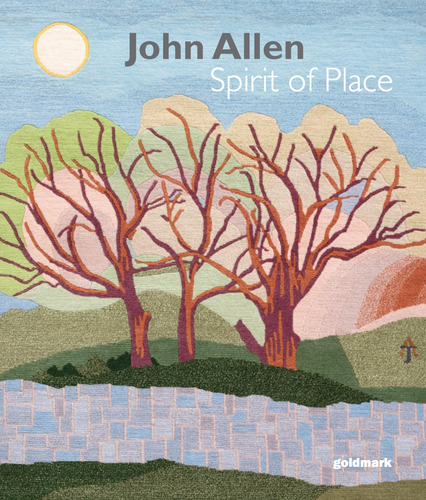

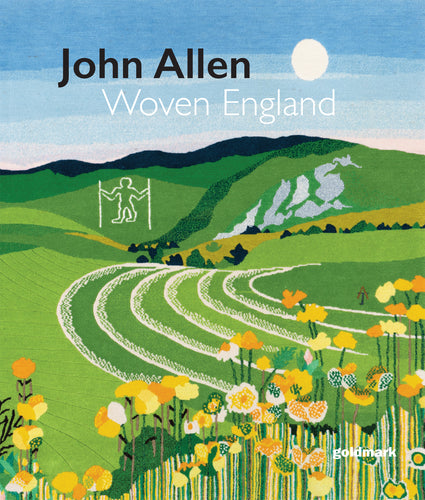

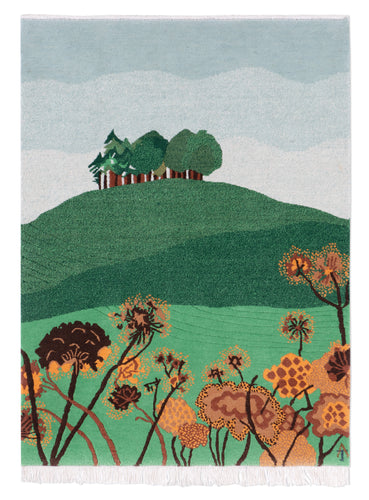

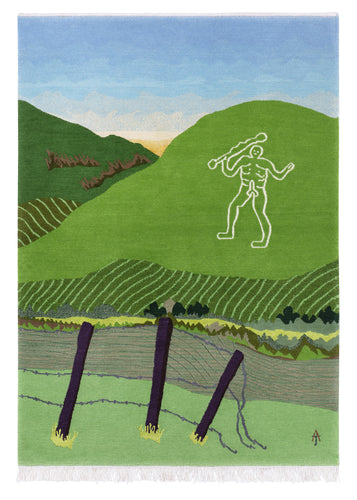

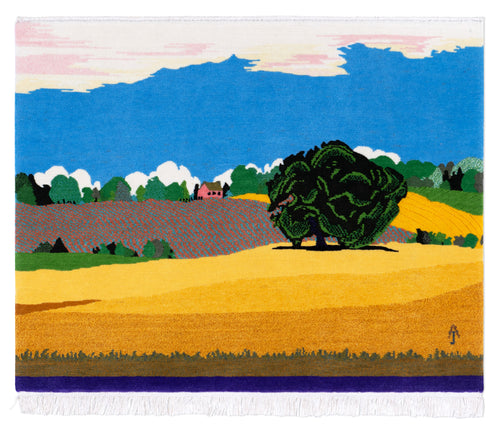

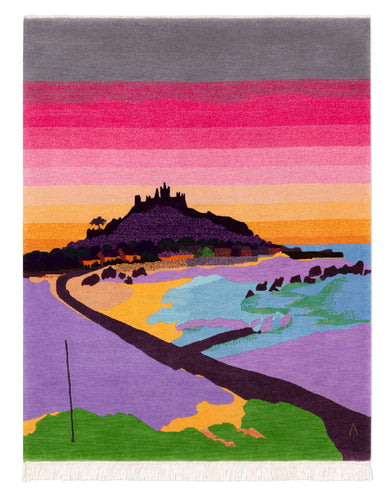

Our nation is, of course, less embattled than it was in those dark days. Yet at a time when Britain’s countryside and coastlines are seldom far from the headlines due to pollution, biodiversity loss and sewage spills, the artist John Allen’s visions of Britain are a balm. Allen (1934–) is, it’s fair to say, a neo-Neo-Romantic. His hand-woven carpets are dense with a sense of wonder at the natural world. Most show rural settings, though urban life does occasionally make an appearance; Big Ben seen semi-obscured by scaffolding, for instance, the artist clearly enjoying the interplay of vertical lines between the poles and the clocktower. But for the most part, the countryside is Allen’s subject. His artworks feature ancient landmarks redolent of the pagan past – Stonehenge, or the giant chalk figures of the Long Man of Wilmington and the Cerne Giant – but never seen as if suspended in some pre-industrial idyll. Through Allen’s eyes, three crooked fence posts with drooping barbed wire are worth as much attention as the Cerne Giant; the shocking strangeness of the club-wielding figure, his penis erect, is placed firmly within the everyday life of the Dorset countryside. This is true for the Long Man, too, as Allen’s eye traces the parallel lines created by farming machinery working a field with as much care as the form of the ancient figure. We are grounded in reality, though that reality is one made gently strange – its colours inverted or displaced, its perspective subtly askew. Baleful moons or pale suns hang heavy in many of his works, lending these vistas the quality of a dream.

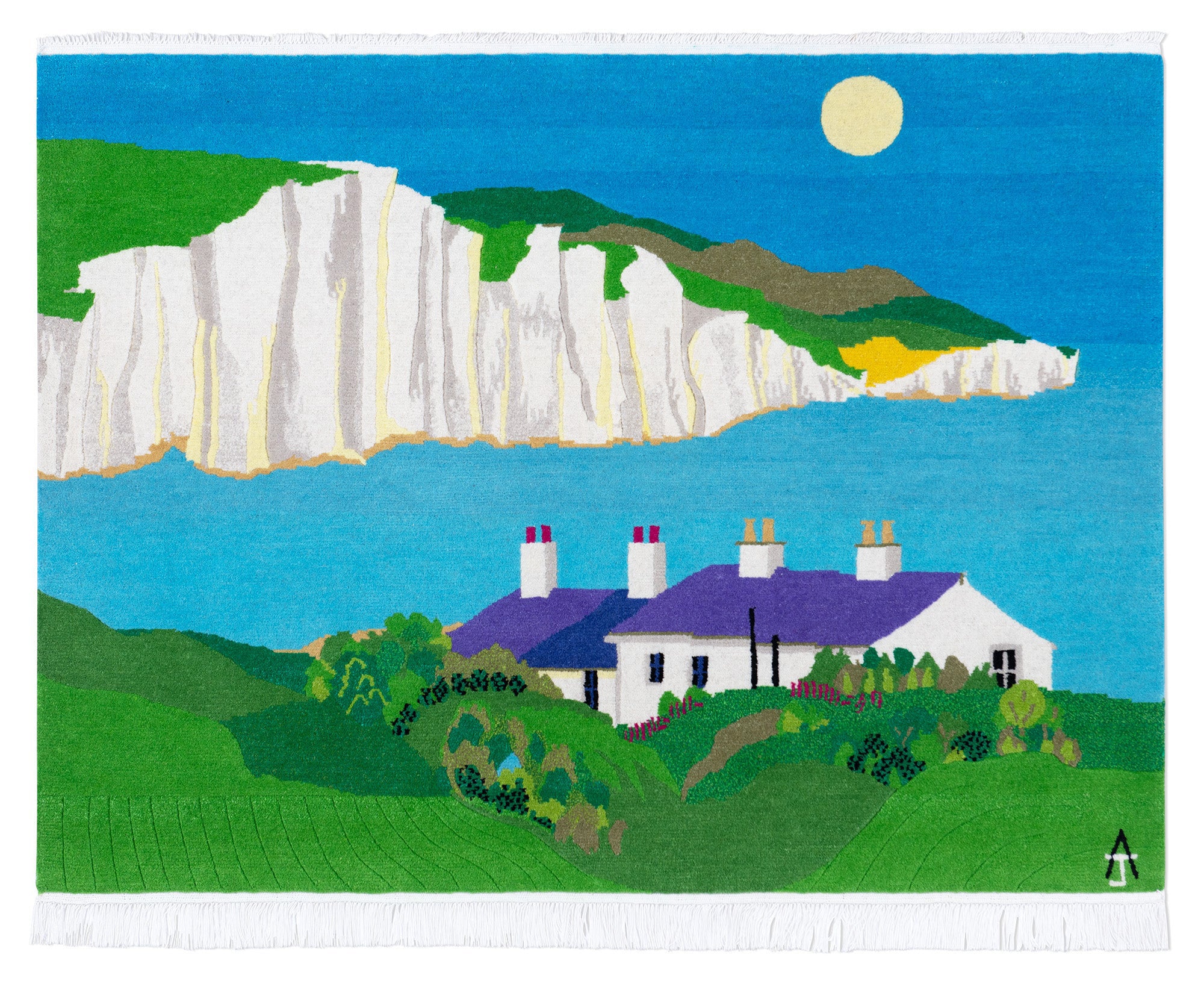

Allen was brought up in Matlock, Derbyshire, on the doorstep of a national park, so his affinity for the British landscape is perhaps unsurprising. What is unusual, however, is the question of degree. Allen describes sitting for hours in beauty spots such as Birling Gap, a beach on a stretch of undeveloped coastline in East Sussex, simply absorbing his environment. What emerged from that particular experience was a new work, in which the white swells of the neighbouring Seven Sisters cliffs and the picturesque Coastguard Cottages are seen from an angle that is, in fact, not quite possible. Rather than a straight recording of the outside world, these are works that depict Allen’s inner landscape. In all his years of work, he has never depicted a person. This has changed in his latest body of work: for the first time, he has included a human figure for the very first time. The inclusion of this figure, a boy flying a kite in Herne Bay, is clearly formal – a compositional inflection point – rather than personal. It’s places, not people, that preoccupy his art.

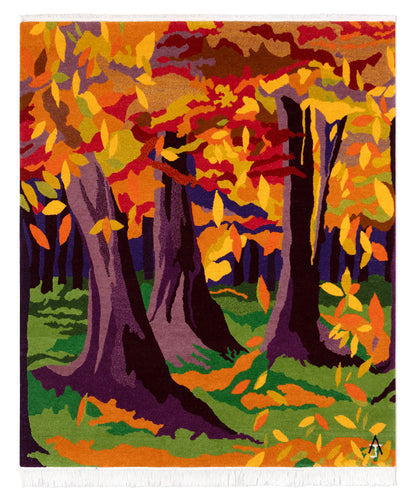

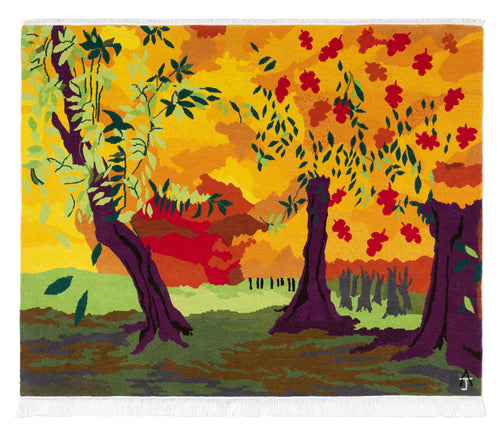

Unsurprisingly, Allen feels a kinship with artists such as Eric Ravilious, Edward Bawden and Cedric Morris, those fellow chroniclers of the English countryside. An impressive crowd of Neo-Romantic works by the likes of David Jones and Tony Giles are clustered in the upstairs hallway of his house, which must be passed through in order to reach his home studio. Though Allen himself now lives in a quiet corner of northeast London, the sky seen through the studio window looks big; as we speak, the setting sun touches the clouds with salmon-pink. The timing could not be better: we are discussing colour, which is a cornerstone of his work. There are the saturated tones of Pop artist Patrick Caulfield, or Op artist Bridget Riley, every bit as bright as those in David Hockney’s work; in another mood, scenes are all but monochromatic.

John Allen photographed in his London studio by Jay Goldmark

Hockney is, famously, a synesthete who sees colour in response to hearing music. Allen experiences a different phenomenon – an emotional synesthesia, whereby his feelings find expression through colour. His landscapes are emotional self-portraits as much as anything else. As he tells it: ‘I'm not interested in either the realism or the abstraction. What I'm really interested in is portraying what I feel when I stand there.’ As a result, unexpected oddities appear within a framework of broadly naturalistic colour. The rocks of Stonehenge are grey, the grass green, but the field behind is bright red; a coastal vista has a blue sea, but the sky is a mustard yellow. His chromatic choices may sometimes be surprising, but they are always precisely judged. Allen agonises over individual shades, often creating dozens of paint swatches before he mixes exactly the right hue. Then, of course, there is the challenge of replicating that same colour, with all the same depth and complexity, into wool or silk yarn.

To achieve all this requires a great deal of communication across cultures. Allen works with weavers in the Kathmandu Valley in rural Nepal, who translate his meticulously gridded designs on paper into three-dimensional works. Himalayan wool is spun, dyed and woven by the artisans according to Allen’s meticulous brief: precisely calibrated colour swatches are posted across more than 4,000 miles in order to ensure that there are no unwelcome surprises when the artist first sees the finished carpets. There is no common language between the artist and the largely illiterate craftspeople – Allen relies on a translator – other than that of their shared knowledge and skill. This allows a kind of communication based on craft: one that sees each learn from the expertise from the other. He cites, for example, the practise of trimming a carpet’s pile to varying depths of relief, adding subtle sculptural interest: a technique the artisans hadn’t yet encountered, but one they soon mastered.

The arrangement is not perfect – newly-paid workers often get drunk and disappear for days on end, deadlines are all-but meaningless, and mistakes can happen that, with his artist’s perfectionism, Allen finds hard to accept – but he is unwilling to change this longstanding relationship. Such an arrangement is too fragile and precious, and the work of establishing mutual trust too onerous, for him to wish to work in any other way. The success of this approach relies on Allen’s depth of expertise: the capacity to know precisely what is possible for a weaver to do, and the knowledge of how to do it.

Across a long life, Allen has travelled a long way from his roots. After training as a dental technician and a few years spent driving a lorry for the family coal business, taking evening classes at a local art college inspired him to make a radical change. He moved to London to attend Camberwell School of Arts, where he studied printed and woven textiles, and then went on to the Royal College of Art to study knitting and weaving. This wide base of knowledge enabled a successful career in fashion textiles, working with couturiers and designers from a studio in Soho, surrounded by yarn, looms and knitting machines. It led, too, to an invitation to set up and teach on a new knitting course at the prestigious Royal College. It was only on retirement in 1995, at 65 years old, that Allen began to make more personal work and to outsource its creation. As he describes it: ‘I travelled to Nepal and saw all this wonderful weaving and thought, oh, that's my real love. I don't want to do any more knitting as long as I live.’

Today, he is uncomfortable with describing himself as an artist, so accustomed is he to the framing of ‘designer’ – but an artist is undoubtedly what he is. ‘I'm an artist, a technician, and a designer,’ says Allen. ‘But I just call myself a designer, because people understand it and I don't feel pretentious saying it.’ This desire to avoid pretentiousness speaks, perhaps, to his working-class background – a background that is increasingly rare in the art world of today. Working-class artists of Allen’s generation benefitted from a system that didn’t exclude those without money for tuition fees; university courses are a sadly different proposition today.

Now, at the age of 89, Allen’s focus is firmly on the future. Although I am visiting in order to discuss the 20 carpets destined for an upcoming exhibition at Goldmark, I find he has little interest in discussing the works he has been meticulously making over the last two years: his mind has already moved on to the next project. This will be a series in which every design features a lane or a road, provisionally titled The Road Goes Everywhere. This idea came from his recent travels around Wiltshire, Dorset, Hampshire and Sussex, while studying works by Ravilious has spurred Allen on – roads appear in many of his pieces – and he is now raring to get started. Another goal: to try and master the rainbow. No small ambition; no artist has ever depicted the phenomenon to Allen’s satisfaction. Nevertheless, he is determined to try. How does he achieve so much at a time of life when most others are winding down? ‘It’s loving life, really,’ he tells me. ‘It’s just all so stimulating.’ It’s precisely this joie-de-vivre that makes his work a joy to behold.

Isabella Smith is senior editor at Apollo magazine and the author of Lucie Rie (Eiderdown Books, 2023). A former deputy editor of Crafts Council-published magazine Crafts, she has written about artists and craftspeople for publications including Frieze, The Guardian, the TLS, and World of Interiors.