Rigby Graham retraces John Clare’s ‘Journey out of Essex’.

In Charles Mapleston’s 1992 film, John Clare’s Journey, life is leaving the artist Rigby Graham behind. He stands in the central reservation as drivers whip by at 60mph, sketchbook in hand, lips sealed like a fist. From a metal fold-out chair, parked amid the nettles in the verge, he draws the train passing where foot travellers once paid a toll for safe passage. Excavators at Leppits Hill turn over the psychic ground where stood Dr Matthew Allen’s private asylum, treads grinding the earth where the poet John Clare may once have lain down to listen to the sounds of the surrounding Epping Forest. The camera rolls, and Graham is left simply to record and reflect on it all. ‘Change always saddens me’, he says, painting the distinctly unattractive vista of the petrol station forecourt in front of him, sandwiched between the nose of a sedan and a mechanic’s truck. ‘Part of me doesn’t like it at all. I like things to be exactly as they were. The other part of me likes change. Because it’s stimulating, it’s living, it’s turning over. You can’t have something that’s static. So I’m aware of the two things. When you think about it you do regret change: bypasses and new roads; but on the other hand I find them extremely interesting. The juxtaposition both irritates and stimulates me, and I think maybe many people feel this. They don’t like driving on motorways, but they always use them!’

This late 20th century tarmacadamed scene would seem very alien to Clare, the great recorder of rural life who died in 1864. But just as the Enclosure acts which he railed against had reorganised the patterns of life and field around him in the early 1800s, so the arrival of the A1 engulfed and streamlined the Great North Road with which he became so familiar, bypassing the villages and alehouses that were, on one fateful journey, his own pitstops. He had, in a manner of speaking, seen it all before: had walked, sat, and watched this sliver of middle England moving on around him, leaving him behind.

Clare’s story is a tragic one. Born into awful poverty, his parent’s labour paid for enough education that he could read and write. He discovered first a love and then a talent for poetry and in 1820 published the collection of poems that propelled him to literary fame. High society condescended to his lowly status, dubbing him ‘the Northamptonshire peasant poet’, but he earned a few loyal supporters. When his celebrity faded, the troubled thoughts he had long soothed with poetry he drowned instead with drink. He was committed to a progressive clinic, at the suggestion of friends and his wife, Patty, but he felt abandoned by all. After four years of confinement, his delusions now all-consuming, he plotted his escape.

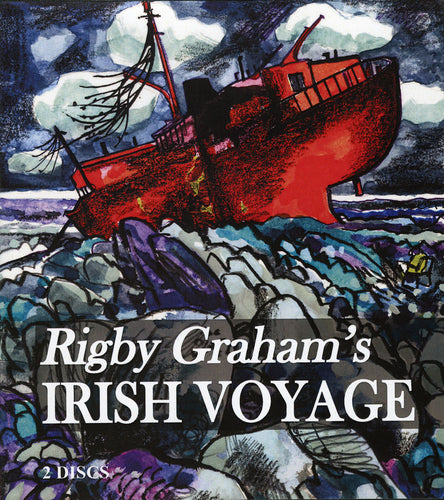

On July 20th, 1841, Clare absconded from High Beech Asylum in Epping Forest, Essex, a gypsy’s hat in his pocket, and set off along the Great North Road on a four-day, 80-mile return to his home in Northborough. On the way he made notes, compiling them in an account of his homecoming titled Journey Out of Essex. 150 years later to the day, Rigby Graham repeated this journey, and where Clare stopped to rest, to write, or to dream, Graham painted.

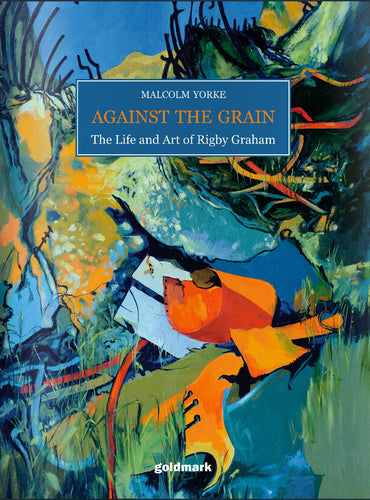

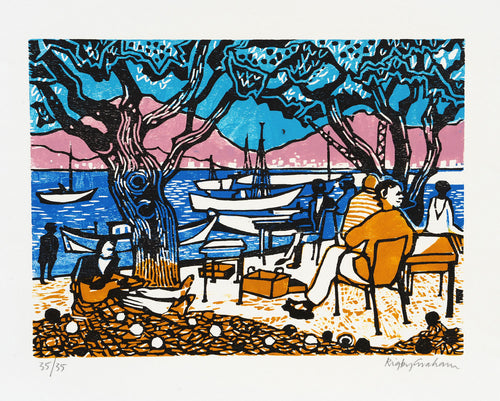

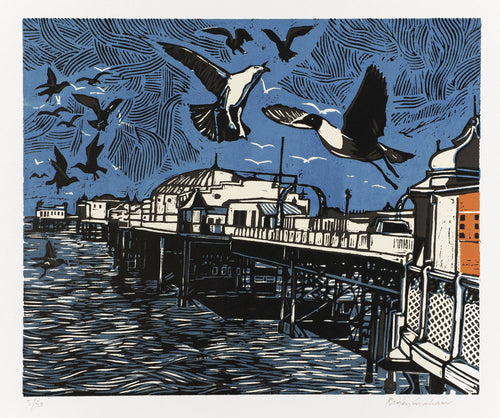

It is now 230 years since Clare’s birth, and a little over 30 since the products of Graham’s homage were first exhibited. The drawings and paintings are all gone, sold: only a pencil portrait of Clare remains, the same sketch over which Mapleston’s credits play (reproduced here on page 33) and which Graham had kept in his own collection. But in the lucid weeks after his pilgrimage Graham found that Clare’s inspiration grew beyond him. He made woodcuts, lithographs and, years later, stained glass on this enduring theme, many of them illustrated here.

Rigby Graham (front left) with Murray Staplehurst in costume as Clare (front right); from behind, Mike and Kate Westbrook, Dave Powell and Liz Cowdrey supply music.

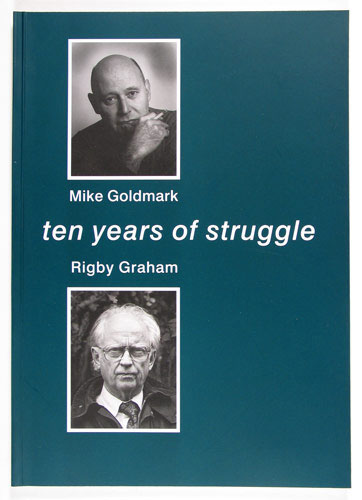

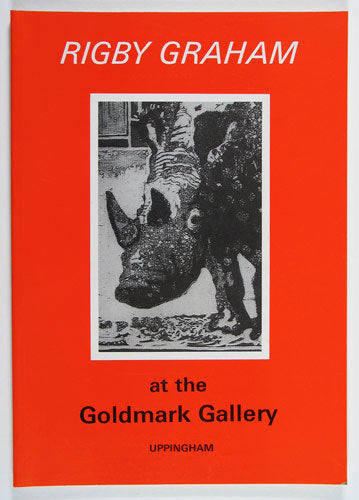

John Clare’s Journey, produced by Charles Mapleston’s independent Malachite Films, screened in September of 1992. Mapleston had previously worked freelance making art films for the BBC and ITV, but it was another of Britain’s great topographical artists that had brought him and Graham together. Charles had filmed Dennis Creffield working on his exhaustive series of drawings depicting the cathedrals of England, for which Mike Goldmark had been the sponsor, providing Creffield with the camper van that facilitated his own cross-country voyage. As Graham’s new representative, ‘now Goldmark was selling me someone new’, Charles remembers. Luckily Anglia Television, with Mapleston’s proposal before them, happily bought the idea of recreating Clare’s odyssey on 16mm film.

Graham’s relationship with Clare predated the film and provided its initial catalyst. He had illustrated Clare’s poems for private press publications from as early as 1959, including the brightly adorned The Toper’s Rant (1974). This vignette of sodden drunkards roused to song at the village pub, ‘stingo’ warm on the breath (a strong local draught), shows Clare’s humorous side, not often appreciated by his literary patrons. But it’s also a portrait of rustic fraternity; of working class pride triumphing over pretentions, penury and miserliness:

‘For our bottle kind fate shall be thanked,

And line but our pockets with brass,

We'll sooner suck ale through a blanket

Than thimbles of wine from a glass.’

London unsettled Clare on his first visit, summoned after the successful reception of his first publication. He knew that writers – especially those living as precariously as he – could be discarded, and when inevitably he was by a fickle readership, he mused on his fate with the knowing melancholy that was a hallmark of his nature writing too: ‘Fame blazed on me like a comet’s glare,’ he lamented, ‘Fame waned and left me like a fallen star’.

Among the promotional materials produced for Mapleston’s film and the attending Goldmark exhibition, Rigby Graham made illustrated broadsheets with typeset reproductions of Clare’s poems. One features the first eight lines of ‘Idle Fame’, which Clare wrote from Northborough in the long wake of his earlier successes, and at a time when ogling visitors would travel to watch the penniless ‘peasant poet’ bend to work in the fields. Evidently it spoke to Graham, who considered himself an acquired taste, and to Mike Goldmark, who delightedly marketed Graham’s work with the tagline ‘specialists in the unsaleable’:

‘I would not wish the burning blaze

Of fame around a restless world,

The thunder and the storm of praise

In crowded tumults heard and hurled.

I would not be a flower to stand

The stare of every passer-bye;

But in some nook of fairyland,

Seen in the praise of beauty’s eye.’

Though the available details of Clare’s early years are scant, the times in which he grew up, and the area he called home, paint a vivid picture reflected in his later poetry.

He was born in Helpston in 1793, halfway between Stamford and Peterborough and on the watery edge of the great Fens, England’s churchly cradle. His parents, literate only in folksong, worked the land to provide him the learning they lacked, but their labour was seasonal and cruelly variable. ‘When times were hard,’ Clare’s biographer Johnathan Bate writes, ‘his father withdrew him in order to save on the fees. When they were very hard, he took his son to work with him in the fields and barns.’ From his father, who was a fiddler, he learnt music and became friendly with the local gypsies. He was perhaps only 8 years old when he was first put to work, threshing with a light flail of his father’s invention. Like them he saved his money for school but left at around 11 or 12 years old, no longer able to afford it, and found teaching instead in rural vocations and his own curious rambling.

It was an inauspicious start to a life of near uninterrupted labouring. Even at the height of his publishing fame, Clare could be found at work in the local countryside. Farming then operated under the old ‘Open Field’ system, a contract of usufruct virtually unchanged since the middle ages. Peasants worked strips of land rented from the local manor, and grazed cows and horses on village commons. As a writer, he considered his craft no different from his work as a farmhand or lime burner, and sometimes despaired that the informal, sing-song style he had worked diligently to shape from boyhood, when he was first introduced to poetry through a volume of seasonal verse, was sometimes taken for bumpkin simplicity or laziness. A local publisher, John Drury, who first discovered his talents wrote excitedly to a cousin in London about his new prospect:

‘Your hopes of good grammar and correct verse depend on the inspiration of the mind; for Clare cannot reason; he writes and can give no reason for his using a fine expression, or a beautiful idea: if you read Poetry to him, he’ll exclaim at each delicate expression ‘beautiful! fine!’ but can give you no reason: yet is always correct and just in his remarks. He is low in stature – long visage – light hair – coarse features – ungainly – awkward – is a fiddler – loves ale –likes the girls – somewhat idle – hates work.’

That cousin was John Taylor, a London publisher who laid claim to having discovered and made Keats’ name too. In 1820, Taylor and Drury became joint publishers of Clare’s first volume of Poems Descriptive of Rural Life and Scenery. They would emphasise and market Clare’s working class credentials as Robert Burns’ promoters had done his. Clare was brought to London to have his portrait painted and to be showed off to literary patrons, like a prize fatstock pig.

Half Clare and the Heron, woodcut, ed 50

Already there were worries for Clare’s state of mind. Drury fretted that his already enthusiastic drinking would soon escalate if he continued to write as frequently and energetically as he did. And his new social status as published poet of note placed him in an uncomfortable limbo state of non-acceptance for which he was ill prepared: neither polished enough for pompous middle class readers, nor downtrodden enough to feel authentically one of his own. Underlying all Clare’s writing were these threats to his identity, reflected in the erosion of the wilder countryside around him, and a sense always of the wolf at the door. The poor house was never far away. And the death of a younger sister at just a year old should remind us that loss was a grim matter of fact for people of his time and ilk.

There is a certain kind of workmanship to Clare’s prideful observation of rural ways of life: the same workmanship Rigby Graham showed when he dressed in suit and tie, even as he battled woodland tangles and stormy elements in search of the right viewpoint for his pictures. He paid respect to the visible furniture of the countryside: ancient oaks, brooks, the old wooden dyke and the passing gate where the milk-maid casts her blushing glances. And in the monotony of the surrounding landscape, which remained Clare’s home his entire life, he found revealed to him hidden riches in its undergrowth. Like Graham, he had keen eyes for little things: the ‘pissmires’ (ants) and the ‘clock-o’-clay’ (ladybird), hiding in cowslips as an oncoming deluge passes, ‘While green grass beneath me lies, / Pearled with dew like fishes’ eyes.’

His impulse to write, to catch at curiosities, was compulsive: he would write on letters, bills, the trim of his hat, or a scrap of bark, to get the idea out and into words. To say that someone has truly ‘lived in the landscape’ is something of a self-obvious cliché, but for Clare (and for Graham, a Leicestershire lad) it becomes a truism. Though he was not strictly a ‘dialect poet’, the regional midlands vernacular creeps sparingly into Clare’s verse like a persistent bramble, clutching with thorns at its neighbours. Many of his heroes were despised by the farmers – yellow ragwort and celandine, both poisonous to grazing cattle. But the great theme of his work, the cycle by which all 28 his subjects lived, was one of tandem predictability and chance. Country life depended on predictions, and was undone by vagaries of weather, or of authorities above and beyond one’s control – as when Graham sits down in Mapleston’s film to sketch with pen and ink and the persistent rain washes his drawing off the page as fast as he can put it down.

Clare once said of Keats that he saw things ‘as according to his fancies’, not as they appeared to himself; for Keats, Clare was too literal. To get a feeling for how the two compare you have only to contrast their two famous nightingale poems. Keats only hears and never sees the ‘immortal Bird’ from his seat beneath the bough of a tree: the voice of the ‘light-winged Dryad of the trees’ transports him with the beauty of its song. Clare by contrast gets his hands dirty, his face low to the ground. ‘Like a very boy’ he creeps on hands and knees ‘through matted thorn’ to see the nightingale’s nest for himself:

‘...I’ve nestled down

And watched her while she sung; and her renown

Hath made me marvel that so famed a bird

Should have no better dress than russet brown.’

Tellingly, it is the birds of the Fens – Clare’s owls, his loping heron – that for Graham became his avatars.

Like the ‘literal’ Clare, scrabbling on hands and knees only to be startled by a scurrying field mouse, young babies hanging from her teats, Graham fastidiously refused to eliminate the sometimes grotesque truth of what was in front of him. ‘I like the vibrancy that uncomfortable things set up. I like the way in which things jar or are awkward, the unexpected colours that you notice, the changing light as clouds go past, or the sun comes out from behind a cloud and you suddenly see light changing on a building. And you see a visible passing of time. It’s like a clock that’s always there, telling you to work harder, because time’s passing, the sands are running away.’

Graham might have called his pictures ‘Remembrances’ after Clare’s poem: a portrait of the old ways, the celebratory rituals and customs of the village parliament disappearing before the imposition of the Enclosure acts. With the privatisation of public land, streams were diverted, woodlands felled, and cross- country paths barred with threat of prosecution. The first acts were introduced in 1809; Clare was just 16, but his economic status required that he work on the enclosure frontline, hammering in the fence posts himself, hacking down local ancient trees:

‘To the axe of the spoiler and self interest fell a prey

And cross berry way and old round oaks narrow lane

With its hollow trees like pulpits I shall never see again

Inclosure like a Buonaparte let not a thing remain

It levelled every bush and tree and levelled every hill

And hung the moles for traitors; ...’

Like the land around him, his poetry resisted this organisation for as long as it could: the words ramble, list, describe, without bending to a narrative, to a principle, to a greater purpose. He published three more volumes, each perhaps better than the last, each to a depreciating audience, until his fears of being forgotten had been realised. Though he had some support through a pension from the Marquess of Exeter, whose gardens at Burghley he had once tended, he worried for his predicament: he had a wife and seven children to provide for. He would eventually pen over 3,500 poems, outliving his publishers who were lost to financial recession, but his health continued to deteriorate. Though his friends intervened and found him a cottage in a nearby village, he finally relented and submitted himself to an Essex lunatic asylum on the advice of his publisher – a progressive institution for its time, where most patients had their run of the grounds. Removed from the way of life he had lived for over 40 years, he soon lost his grip on reality. He thought he might be Lord Byron, one of his favourite poets, or a prize-winning fighter. And he began to dream again of Mary Joyce, his lifelong muse, the daughter of a ‘slightly better class of farmer’ whose father had forbidden their adolescent relationship.

It is here that Mapleston’s film picks up the story, when Clare undertook his ‘Escape from Essex’, diarising as he walked with thoughts of returning to an hallucinated bliss with Mary; in fact she had died some years ago. The trek was long, his diet limited to roadside weeds and the occasional bread and ale, paid for with the pennies of charitable passers-by. Only as he neared Glinton did he learn of Mary’s fate, when a woman jumped from a cart in the road ‘and caught fast hold of my hands, and wished me to get into the cart. But I refused; I thought her either drunk or mad. But when I was told it was my second wife, Patty, I got in, and was soon at Northborough. But Mary was not there; neither could I get any information about her further than the old story of her having died six years ago. But I took no notice of the lie, having seen her myself twelve months ago, alive and well, and as young as ever. So here I am hopeless at home.’

With a modest budget for just six days shooting and a cutting room limit of 25 minutes, Mapleston’s planning as they came to recreate Clare’s journey was meticulous. Key research involved purchasing original sheets of the first series Ordnance Survey maps, published at the same time as Clare’s poetry, on which to trace Clare’s route from facsimile reproductions of his notes.

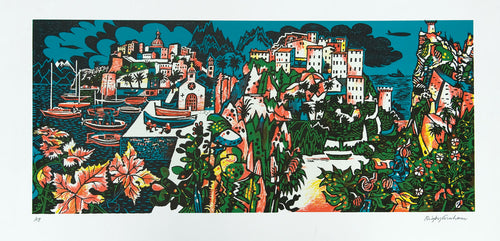

‘Although it is still possible to find many of the places Clare wrote about in his journal’, Michael Jayston’s voiceover tells us, ‘Rigby Graham, perversely, is looking for contrasts’; in fact contrasts and coincidences had been at the forefront of Mapleston’s mind as he drafted their approach. He had been delighted to find that on a site near Astwick where Clare had sat on a small pile of flint ‘and made a good many wishes for breakfast’ there now stood a Little Chef. The red brick facade of Buckden presented its own chance eccentricity when, as Graham sketched, a man road by on a bicycle with an old cast- iron lawnmower on his shoulder – ‘perhaps a gardener, on his way to lunch.’ He was soon immortalised in Graham’s lithograph of the Bishop’s palace; above the slate roof the typical Graham inclusion of a tiny television aerial peers into view. And it seemed only right, given that Clare was among the first proper chroniclers of local folksong and his ‘brother bards’, that the merry dancers of Peterborough Morris should feature, with their resplendent attendant cockerel.

John Clare by W. W. Law, albumen print, 1862

As is to be expected, much has changed yet again in the 30 years since John Clare’s Journey was made. Little Chef, once a staple of ‘90s roadside cuisine, is now gone the way of the flint pile. The Alconbury milestone where Graham stood and drew in the central reservation has been since craned to a new (and presumably now inaccurate) location. And the pebble- dash graffiti adorning a Peterborough waterside home – ‘NO TO THE POLL TAX’, a communal burden for the 20th century, implemented from on high – has been scrubbed and painted over, lost to sanitising time.

‘A road comes from the past, and goes into the future,’ Graham says. The past soon caught up with Clare. Before long he was captured again, and secluded at Northampton General Lunatic Asylum, where he was to stay another 20 years, dying in 1864 aged 71. His wife did not visit. As his mind slipped further into quiet despair, an enlightened superintendent helped record his last poems, published posthumously. But for a man born and bred in the fields, institutionalisation came as yet another form of enclosure. He described how the letters, the vowels, had been squeezed from his head by his captivity. His last letter to an enquirer is deeply sad, ending poignantly in a vow of helpless silence:

Dear Sir

I am in a Madhouse & quite forget your Name or who you are you must excuse me for I have nothing to commu[n]icate or tell of & why I am shut up I don’t know

I have nothing to say so I conclude

Yours respectfully

John Clare

But a strange circularity surrounds Clare’s tale: this story within a story, an episode beginning and ending with captivity but seems to breed poppy-like perennial repetitions. Thanks again to a chance remark by Mike Goldmark, Mapleston’s film provoked another project: Iain Sinclair’s Edge of Orison (the title is Clare’s from Journey Out of Essex), another retreading of Clare’s path, by foot and not car, in search of connection: Sinclair’s wife’s family claimed longlost links with Clare. Fellow second-hand book dealers, Mike had published Sinclair’s very first novel, White Chappell Scarlet Tracings, sight unseen, in 1987. The handwritten dedication in Mike’s own copy of Orison reads: ‘Another one to unread.’ Reproduced opposite is the only photograph we have of Clare, long in the asylum, all identifiable youth and vigour burnished out of him, his signature arthritic and unsure.

Edge of the Orison has since prompted another film – By Our Selves (2015) from Andrew Kötting, a director with whom Sinclair had worked before. In it the actor Toby Jones walks Clare’s journey once more, and in doing so recreates the performance of his own father, Freddie Jones, who walked and talked as Clare in a 1970 BBC Omnibus documentary. Kötting cameos as the giant straw bear, straight out of The Wicker Man (and not unlike the Peterborough cock) whose presence suggests Clares’ disintegrating sense of the world around him.

Portrait of John Clare, pencil, 1991

If Mapleston’s film, Graham’s pictures, Sinclair’s book or Kötting’s fever-dream tell us anything, it is that rites of passage recorded in memory will always demand recreation, like a holy pilgrimage, and with each retreading be transformed again. The words have put down roots, and no amount of change – superficial or catastrophic – can drag them from the ground. ‘The track we travelled, coming from London, is no longer Clare’s Great North Road’ Sinclair writes. ‘Through error, perhaps, we arrive at a richer truth: in the telling is the tale. The trance of writing is the author’s only defence against the world. He sleepwalks between assignments, between welcoming ghosts, looking out for the next prompt, the next milestone hidden in the grass.’

Clare’s body now lies in Helpston, his final homecoming. And one day of every year, in honour of the ‘peasant poet’, school children lay flower cushions round his grave. As he slept on his flight from Essex, buttressed against a clover bed, Clare now sleeps on a bed of flowers, Mary not so very far from his side.