Prints generally offer incredible value for money, allowing many of us to own original works by famed artists like Picasso or Rembrandt for mere fractions of the price of their oil paintings and drawings.

But they can also be confusing for prospective buyers: they come in different editions, can be signed on the page, in the plate, or not at all, were sometimes printed by the artist and at other times by their preferred printer. It's difficult to keep track of exactly what it is you're looking at and how many others like it are out there.

Here are 3 of our most frequently asked questions from our customers when it comes to prints.

1. How can you have an ‘original’ print? Aren’t prints just copies?

Surprisingly this is perhaps the single most common question we get asked at the Goldmark Gallery, and it’s a really tricky one to answer clearly and succinctly.

The term ‘original print’ can be confusing to those who haven’t come across it before. The word ‘print’ to most people means a ‘copy’, like copies of a newspaper or reproductions of an oil painting.

An original print is called ‘original’ because it isn’t reproducing an image which already exists. The artist has intended from the very start to create their artwork using a graphic medium – a suite of etchings, say, or a one-off screenprint – and designs the image with that medium in mind.

Once the design is finalised and the plate, block or screen from which the print will be made is complete, multiple runs of each image are produced, making an ‘edition’.

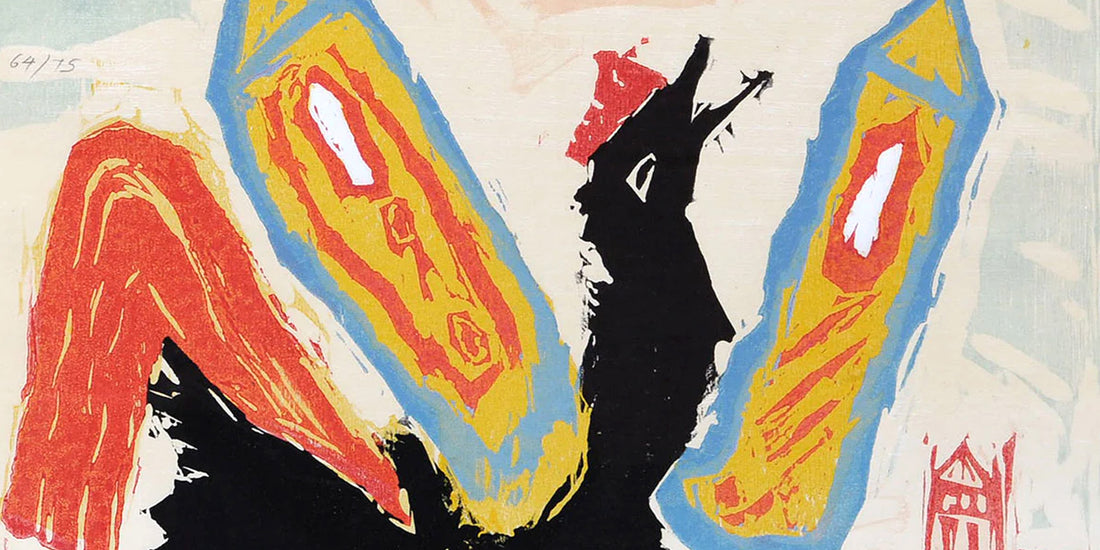

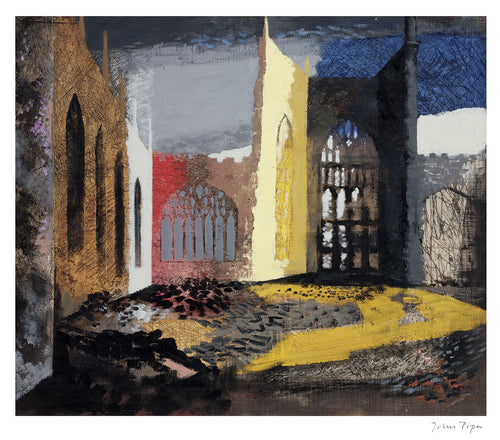

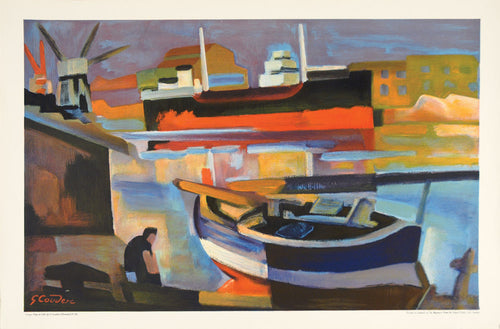

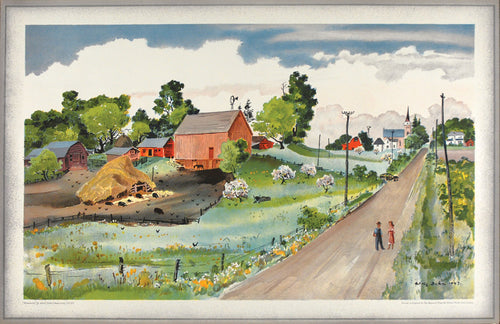

a reproductive screenprint of a John Piper oil painting (left); an original screenprint by Piper (right)

a reproductive screenprint of a John Piper oil painting (left); an original screenprint by Piper (right)

An original print itself won’t be unique – it may be one of an edition of 20, or it may be one of 1000, depending on how many runs the artist decided to make.

But the image will be unique – it will always have been intended as an etching, or a screenprint, or whichever print-type the artist originally chose to work in, and not a copy of a previous work.

2. How can I tell if a print is the real deal?

A good first port of call when trying to tell if a print is authentic or not can be a simple google of the title and the artist. While it sounds obvious, searching online to see if the print has been sold elsewhere through a reputable dealer or auction house can quickly eliminate any initial doubts about the print's existence.

Whenever we are offered a print to buy at the gallery, the very first place we look after an online search is in that artist’s catalogue raisonné. These are comprehensive books that list all the works by an artist and provide the essential information by which those works can be identified.

a catalogue raisonné of John Piper's prints by Orde Levinson

a catalogue raisonné of John Piper's prints by Orde Levinson

Often artists will have specific print catalogues raisonnés produced about them, listing all the graphic work they have undertaken. Here you can find more particular details about the print you are interested in, such as the date it was printed, its publication format, and the size of the edition.

If you can’t find the print in a catalogue raisonné, then you might have some cause for concern, though there can often be good reasons for an omission; sometimes scarce prints are discovered after the catalogue has been published and publicised. This is why there are often multiple catalogue raisonnés on the same artist, each new edition updating the information of its predecessor.

a Picasso faun with the accompanying justification page for its suite

a Picasso faun with the accompanying justification page for its suite

Galleries will also be able to offer you information about a print’s provenance. Since the post-war period limited edition prints have occasionally been produced with accompanying ‘certificates of authenticity’ or ‘justification pages’, documents that verify a work’s title, edition size, and date of publication.

In the circumstances where an earlier print has been produced without an authenticating document, you can ask about its previous ownership: has it passed through any major auction houses, or was it sold from the artist’s estate or by a friend or relative?

3. These two prints seem identical but they have different prices - why?

There can be many reasons for price variations between seemingly identical prints, some less obvious than others.

The most obvious difference may be that one print has been signed by the artist. An artist’s signature can add to the price of a print for the kudos it provides, the knowledge that the artist’s hand has been involved in its production; it can also lend an authenticity to the print, confirming that it isn’t a copy or a later reprint.

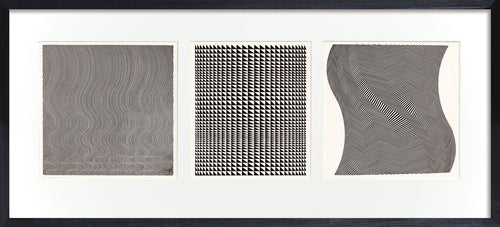

a signed etching from David Hockney's Grimm's Fairytales suite, numbered '52/100'

In other cases a price difference may be due to subtle differences in the details or the quality of a print. Is one, for example, hand-coloured in places? Perhaps one is slightly faded, or features foxing – brown or grey discolouration caused by humidity – around the edges of the paper.

Less obvious may be differences in the editioning of each print. Prints produced ‘aside’ from the edition, such as Artist Proofs, are often more expensive for their scarcity, despite appearing identical to the normal editions.

Certain editions of prints will also be regarded as ‘specials’. While there may be 200 prints in a regular numbered edition, the artist may produce 50 specials that are marked differently (with Roman Numerals, for example) or are printed on higher quality sheets of paper.

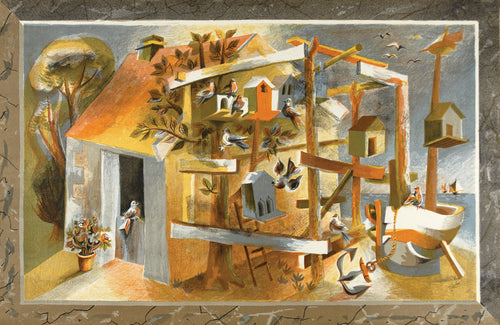

a Goya etching from the 6th edition of Los Caprichos (left) vs. one of the earliest impressions from the 1st edition (right)

Where there are multiple editions of a print produced over several years (and even decades or centuries), there can also be discrepancies between each edition that will affect a print’s price. The more editions that are produced, the more likely the blocks or plates used to print from will be damaged, meaning earlier editions are often more sought after for the quality of their image.