When Augustus John arrived at the Slade School in 1894, he was a Welshman in London; an unkempt country lad transposed to urban Bloomsbury. From his buccaneering dress sense to his outrageously prodigious drawing talents, he stuck out among his Gower Street peers like a sore thumb.

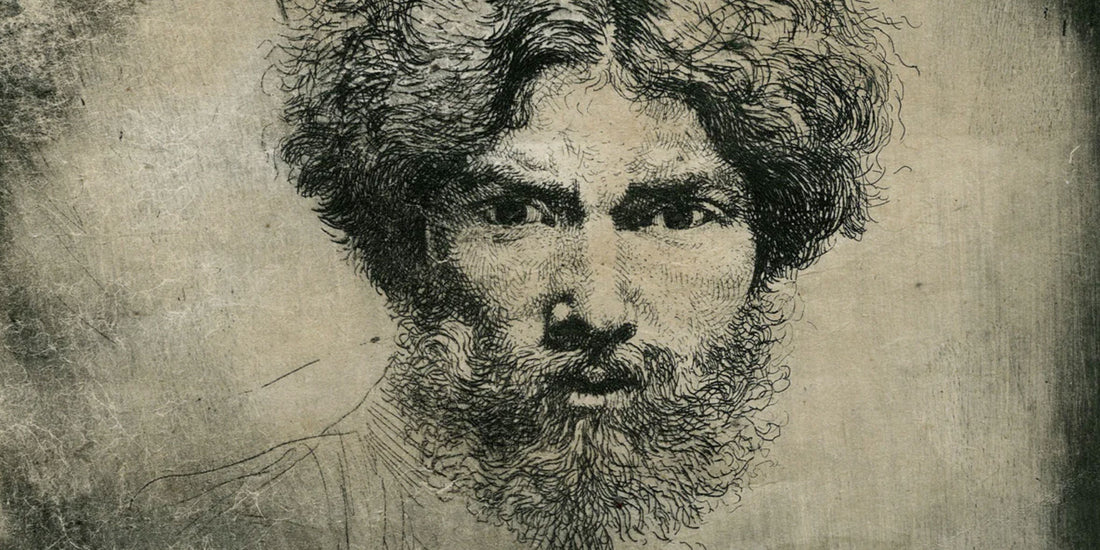

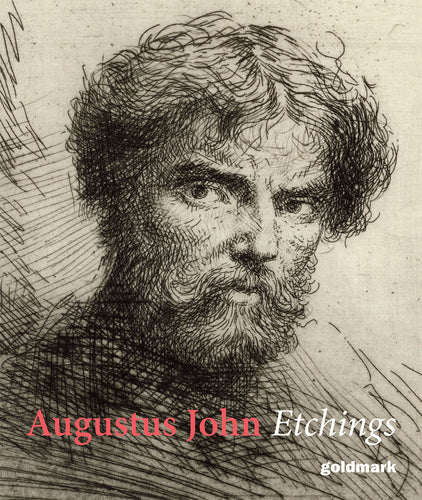

self-portrait

self-portrait

Individualism – or rather Outsider-ness – was to define and dominate his life. He was outwardly brash, self-confident and cavalier, while nursing inward doubts. To escape the isolation of his own uncertain company, he surrounded himself with a – sometimes literal – caravan of progeny and paramours: Ida Nettleship, the artist wife to whom he ‘conceded’ marriage (though the institution suited neither of them) and who, self-dubbed ‘the Belly’, would bear him five sons in as many years; and Dorelia (née Dorothy) McNeill, the enigmatic young courtesan who gave birth to their first son together in a gypsy wagon parked in the hills of Dartmoor.

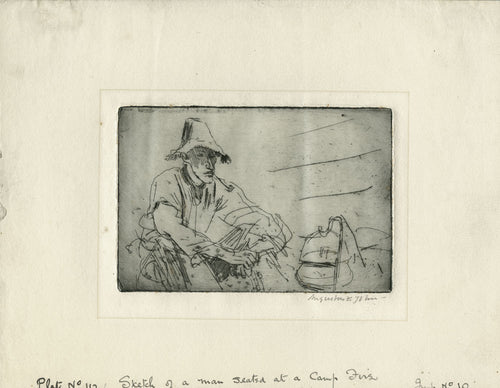

view of John's legendary gypsy caravan

view of John's legendary gypsy caravan

John himself was born in Tenby, Pembrokeshire in 1878. At the age of six he suffered the loss of his mother. It was she, an amateur artist (and the more sympathetic of his parents) who first encouraged the young Augustus and his elder sister Gwen in their discovery of ‘the mystery of painting’. Their careers would develop in parallel: Gwen, the more softly self-possessed, demure - dressed all in black - but determined, intractable; and ‘Gus’, the extrovert who craved companionship and reassurance.

portrait of Gwen John

portrait of Gwen John

Both would be established through portraiture, though she was, by historic consensus, the more consistent painter. While Gwen’s austere female portraits went from strength to strength under the influence of Whistler, John was plagued by flashes of brilliance amid furious self-aborted efforts - a qualitative seismograph to Gwen’s steady upward curve. Though he sustained a celebrated career as Britain’s preeminent high society painter, his best portraits were less frequently commissions and more often, tellingly, paintings of like souls: family, artist friends, writers and patrons, fellow pupils, and the vagabond strangers who had so fascinated him as a child. These he would portray not just in paint, but most emphatically in the etching plate. Printmaking marked a definitive point of divergence in his and Gwen’s careers; it was also where John’s true brilliance lay. Comparatively little has been made of his graphic work - perhaps because it seemed so much less important to himself - yet in etching, he achieved a level of expression to match the Old Masters. What they lack in colour and expansive size, in the impatient gestural slashes of paint that typify his oils, they make up for with exquisite emotional confession.

portrait of Ida Nettleship, John's first wife

portrait of Ida Nettleship, John's first wife

After their mother’s death, care of John and his siblings fell to their father. He was a solicitor – colder, and hopelessly detached – who, despite public fastidiousness, in private left the four children to their own devices. For John, who would build a lifestyle on non-conformity, his father’s dry insistence that the family derived from ‘a line of professional people’ kindled a catalytic distrust of orthodoxy: ‘I wanted to be my own unadulterated self, and no one else. And so taking my father as a model, I watched him carefully, imitating his tricks as closely as I could, but in reverse. By this method I sought to protect myself from the intrusion of the uninvited dead.’

study of a nude girl seated

study of a nude girl seated

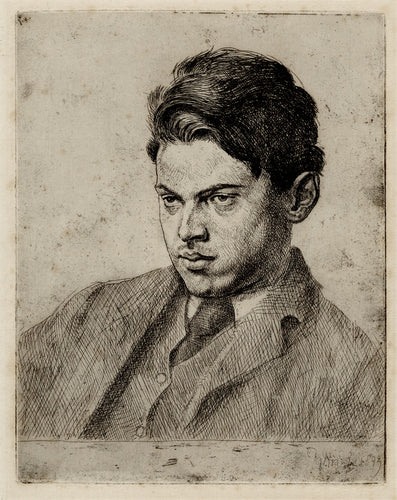

He arrived at the Slade at the age of sixteen, Gwen hot on his heels. A born draughtsman, John flourished in the life drawing department under the robust teaching of Henry Tonks, the former surgeon turned art teacher. His sketches – evidence of a untaught, untamed precociousness - were widely circulated around the Bloomsbury halls and quickly garnered him a legendary status, one he saw fit to embellish. Initially shy, with confidence he began to cultivate a dashingly Dionysian self-image based on childhood observations of Romani travellers, replete with thick beard, fine tailored tweeds, and a rakish smoking cap of black velvet.

study of a Rabbi reading, after Rembrandt

study of a Rabbi reading, after Rembrandt

It was here too at the Slade that John learnt how to etch. Intaglio printing made for a natural transition from the pencil and chalk drawings that had marked him out as his generation’s promising talent. His early etched portraits, achingly direct in their description, bore the unmistakable hallowed touch of , but to John, they constituted little more than leisurely exercises. Preparation of the plates and the acid bath made etching a more protracted affair than painting or life drawing, and he may have enjoyed its measured change of pace, the opportunity to review and revaluate each impression. It was not until 1906, some six or seven years into his professional career, that the first collection of his prints was collated and published commercially.

pastoral scene, possibly inspired by John's joint relationship with Dorelia and Ida

pastoral scene, possibly inspired by John's joint relationship with Dorelia and Ida

By now John had met his first wife Ida, a fellow student at the Slade. With the birth of their first child due in 1902 he was forced to seek a more stable income, finding employment as an art teacher in Liverpool at a school attached to the University College. Though his stay there was short, it produced a series of etched plates that quietly established him as a new master of the medium. Etching is not a forgiving process; its thin, resin ground presents a peculiar waxy resistance to the needle, quite unlike the rapidity achievable with graphite, yet John’s plates reveal all the intimacy and immediacy of pen or pencil on paper. He scratched as he sketched – varying pace and detail, from methodically built up passages of cross-hatching to delicately spare arrangements of whispered, spidery lines. As with his oils, most early compositions were portraits; a favoured technique, one he may have adapted from Rembrandt, was to surround the edge of the plate with dense, vigorous, inward strokes, bathing his subject in a halo of bright light that recessed into hatched darkness.

portrait of 'Old Arthy'

portrait of 'Old Arthy'

As Augustus’ career in portraiture began to take off, Ida’s was subsumed by motherhood. They were not natural parents: Ida came to resent the role of child bearer and craved the liberty of her student days, while for John, his offspring represented little more than a source of painterly focus. Their domestic life, if not bliss, was certainly colourful (John famously taught the family parrot to swear in Romany), but the arrival of Dorelia via Gwen, who had first discovered her, disturbed what little stability they had, turning their relationship to a frustrated, polygamous ménage à trois. Both women sat extensively for John, forfeiting their own art for the sake of their husband. ‘I would rather lose a child,’, Ida wrote to Gwen, ‘than the power of sitting. The longer I live the more subordinate do all things become to that old A.E. (Augustus Edwin) the monster.’ They were at once competitors for his attention and intimate companions in their rejection of his more capricious moods, when they would take the children to Paris on their own, leaving John to sulk in his London studios (‘Our great child artist’, Ida wrote: ‘Let him snap his jaws.’).

'Quarry Folk', revealing John's preoccupation for pre-industrial life

'Quarry Folk', revealing John's preoccupation for pre-industrial life

For John, the next ten years were a decade of intense restlessness. He had begun to envisage their lives together as a modern-day incarnation of pre-industrial gypsies. Traveller folk and their attending band of ragamuffin children had long captivated him, with ‘those sardonic faces, those lustrous oriental eyes…Aloof, arrogant, and in their ragged finery somehow superior to the common run of natives, they could be recognised a mile off.’ His etchings from this time were all borne on a fanciful vision of rustic traveller life as he moved the family between Dartmoor, London, and Paris, bivouacking off rivers and roadsides in a hand-painted caravan. He had Ida and Dorelia don Bohemian dress, or arranged locals in fisherwomen garb, painting and etching them into imagined pastoral vignettes. After Ida’s sudden death in 1907 from a postpartum infection, Dorelia’s presence became ever more dominant as the troupe moved once more to Provençal France. She was a gifted sitter, with a timeless face and smouldering Mona Lisa smile that lent authentic life to John’s fantasy scenes.

portrait of Dorelia McNeill, perhaps John's best-known mistress

portrait of Dorelia McNeill, perhaps John's best-known mistress

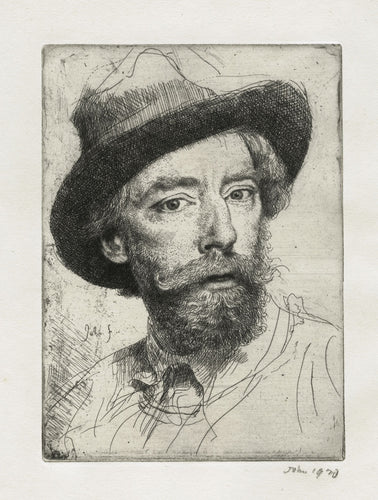

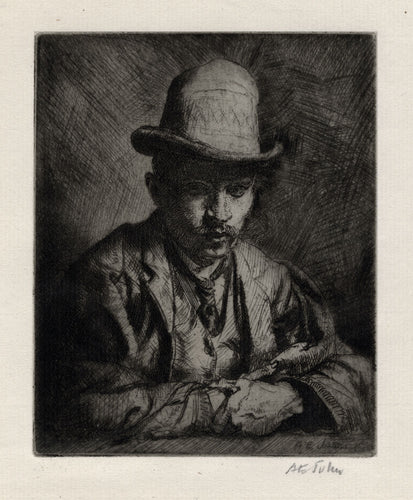

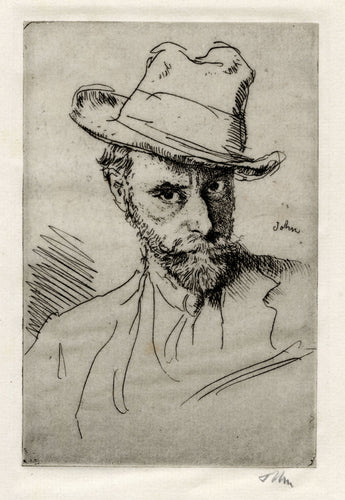

The drawings had changed too; his touch was swifter, fleeting, his portraits produced with an increasingly economical summary of line, the bare sheet of a miniature etching scattered with hard-pointed details. Of the many he produced, it is perhaps the self-portraits that move most. Superficially charismatic, with tousled hair and beard, hats perched jauntily on a head tilted to one side, the insouciance of the pose is undercut by the absolute directness of the gaze: in these few portraits, he teases out moments of utter vulnerability from his projected sureness.

portrait of the artist

portrait of the artist

In the intervening years, as John’s portraiture found him commercial success, printmaking was slowly subsumed by painting; he made no etchings beyond the First World War. Appointed briefly as an Official War Artist after being rejected for military service (he was notably the only recruit, bar King George, permitted to keep his beard), the post-war years were a time of celebrity commissions and a rise to public prominence. Elected a Royal Academician late in 1928, in 1942 he was awarded the Order of Merit and, ten years later, had his first autobiographical work Chiaroscuro published by Jonathan Cape (the second volume, aptly titled Finishing Touches, appeared posthumously some twelve years later).

portrait of a serving maid

portrait of a serving maid

John wrote as he had lived: whirling from one personage to the next, his rambunctious, anecdotal prose punctuated at unpredictable intervals by moments of candid, and sometimes painful, self-revelation. At its best, the text – some thirty years in the making – was like his portraits; it offered, if not clinical realism, a glimpse into the internal wrestlings that had pervaded so much of his life: admissions of estrangement, desire, loneliness, and a preoccupation with sex that bordered on the priapic (one spurious account recalls an encounter with a hermaphroditic model – like a ‘Greek ideal’ – in Paris: to John’s bold inquiry as to what the young woman did when in an amorous mood, the delightful answer, ‘delivered without hesitation, to my naïve and really inexcusable impertinence’, was ‘Mais Monsieur, je me masturbe.’).

'The Valley of Time', another scene of primitive bucolia

'The Valley of Time', another scene of primitive bucolia

Through his twilight years John’s output slackened as he struggled to acclimatise to encroaching old age. His last canvases grew ever larger, barer. Many were left totally unresolved, as if the wooden frame of the stretcher were shrinking beyond reach with every effort to contain and shape his fading bucolic vision. He died in 1961, aged eighty-three years old, at Fryern Court, the secluded Hampshire house where he had established a studio in the late 1920s.

small self-portrait

small self-portrait

The writer Norman Douglas spoke of John as ‘the last of the Titans’. Like the Ancient Greek pre-deities of the same name, he too was ultimately cast into oblivion by the new gods of the post-war art world. In death, as in life, he was an artist outside his own time. He had lived too long, still fruitlessly painting at a time when his particular vein of individualistic traditionalism was far behind the current vogue. His art was untrammelled by loyalty to any school or strain; though for a brief time he had conjured a Symbolist following, painting in Wales at the foothills of Mount Arenig with the lunatic painter J.D. Innes, for the greater part of his career he remained an outsider; the itinerant tomcat of Fitzroy Square, roaming between gypsy idylls in Southern Provence and his private London studios.