Dame Barbara Hepworth, it is fair to say, was not naturally suited to partnership. Her intensely personal, and protective, attitude toward her sculpting practice was reflected in the testimony of her lifetime assistants – all 16 of them – who laboured under her employ. She was by their accounts often shy, nervous, tense and ill-tempered, and guarded against the accusation that some of her carving work was delegated to others (normal practice, of course, since the Renaissance and beyond).

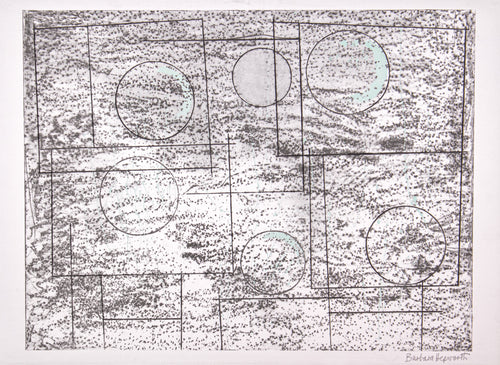

The suggestion that she might produce a series of lithographs with Stanley Jones, who had introduced her to the medium a decade earlier, was a bold one. A project like this, in which collaboration was to form such a strong element might have proved disastrous. But their association (explored in our previous issue), however brief, proved immensely fruitful. An original drawing by Hepworth long in Stanley’s possession, which served as a maquette for one of these prints, provides a fascinating view into their working relationship.

Barbara Hepworth, Three Forms in Echelon, 1960s, chalk and crayon

Rosemary Simmons, founder of the magazine Printmaking Today and a veteran of the printmaking world, worked with Stanley at the Curwen Studio in the 1960s. For her, the maquette provides the essential insight into how ‘it was all about balance with Barbara. It shows how the background colour was strengthened as well as the centre bottom black lines in the final lithograph. So the drawing is an interesting state in the making of the print. I am sure that it is Hepworth’s first idea. She made numerous such drawings and discussed them with Stanley as to what would work lithographically, such as the effect of coloured inks on absorbent paper. I expect they decided that the background orange was too textured in relationship to the black lines, and having strengthened the orange the central bottom black bits had to be strengthened too.’

Barbara Hepworth, Three Forms in Echelon, 1960s, chalk and crayon

The background itself appears to have been achieved through frottage – ‘capturing the texture of wood or another surface like a brass rubbing’, writes artist Susan Aldworth, who also made prints at Curwen. ‘Stanley got me to do the frottage for my print so that it was my marks and not his that he would capture on the final print. I’m sure this would have been the way he always worked.’

Barbara Hepworth, Three Forms (from the Twelve Lithographs Suite), lithograph, 1969

The closest sculptural equivalent to Three Forms is the alabaster carving Three Forms in Echelon, carved in 1963 (with several comparable drawings dating to the same year); but by the time Hepworth was working on her first major series with Jones, more recent sculptures included several cut or cast in metal. I remember seeing one of these, Two Forms (Divided Circle), on trips to Dulwich Park: designed in 1969 and installed in 1970, it was an exact contemporary of Hepworth’s Twelve Lithographs series. I would often walk past it on childhood trips to the park, visiting grandparents who lived in nearby West Norwood. Hepworth once described how she used to try and get inside and around her largest sculptures, feeling how her own body fit among and within them, something I remember seeing children do in the park.

I also remember learning from the tiny television set in my grandparents’ kitchen that in 2011 it had disappeared, likely stolen by scrap-metal thieves. It seemed a deeply cynical and depressing loss – but in truth, the work had always felt a little out of place on the Dulwich lawns, the grass around it ground to a denuded brown by the feet of playing children and tourists. The whole thing seemed forlorn on such a flat expanse of grass, neutered by the formal black nameplate that stood in front of it.

It was only on seeing photographs of Hepworth’s studio garden, and then visiting some years later, that this awkwardness made sense. Here her sculptures seemed to be completed by their closed environment, the play of light and shadow cast by the forms of leaves in the wind, and the view of other sculptures past and through one another. Far from seeming cold and puritanically geometric, as her work was sometimes criticised, here even her tallest, most imposing abstractions came alive in an environment of human scale, perspective, and touch.

Barbara Hepworth, Two Forms (Divided Circle) in Hepworth's garden

For me, this drawing takes me back to that enclosed setting, where you are always looking not just at but around and through Hepworth’s art. I like to imagine her rubbing over the surface of her paper, laid perhaps over a block of wood or stone in the studio, mapping out her arcs like a cartographer with a compass, divining the place of a circle like a modern-day astronomer or ancient shaman charting the passage of the sun.