Japan is home to the oldest known ceramics in the world. The story of Jomon pottery, the earliest examples of which date back some 15-16,000 years ago, is strange and compelling: its creators formed their first clay vessels before their people had discovered the essential technologies of agricultural production and basic metallurgy. Its origins can be traced back to the same period in which the Shinto religion, Japan’s native faith, was born.

For Japan, the history of ceramics is the history of its belief systems, its cultural values, its wars and dynasties - to a greater or lesser extent, it is the history of its people. And yet, at the beginning of the 20th century, it looked as if Japan’s traditional ceramic production was becoming obsolete.

Yohen vase by Ken Matsuzaki

Yohen vase by Ken Matsuzaki

Extreme isolationism over the preceding centuries had had an immense impact upon the country's ceramic industry. Shut off from cultural exchange with the world, save for the influx of teawares brought home by monks from China, ceramic spoils from invasion campaigns in Korea, and European traders peddling their earthenwares, Japanese potters were essentially left alone to their intense self-scrutiny. Heavily influenced by imported pottery, native makers constantly assessed and reassessed desirable qualities of glazes and firings in response to these new styles.

(above) Natural Ash Jar by Ken Matsuzaki; (below) two chawans in the Iga (left) and Shigaraki (right) styles by Kazuya Furutani

(above) Natural Ash Jar by Ken Matsuzaki; (below) two chawans in the Iga (left) and Shigaraki (right) styles by Kazuya Furutani

As potters gained preeminence navigating the strictures of the tea ceremony and the noble lords who dictated its ritual aesthetic, many of the styles of Japanese pottery we now know and celebrate – Iga, Shigaraki, Bizen, Shino, Oribe – emerged at specialist kilns, each one succeeding the next in popularity and promoting their work as the preeminent style befitting chanoyu and the ceremonies of the ‘Way of Tea’.

But by the 18th and 19th centuries, the world of international trade beckoned. The demand was for porcelain, and China had already opened its floodgates to Europe’s desires for blue and white ware. With natural porcelain sources discovered throughout the Japanese islands, the country was lured down a similar path, and as industrialisation, urbanisation and the age of the machine reared its head in the late 19th and early 20th century, it seemed the diminishing fires of the traditional pottery kilns were to be extinguished altogether.

Shoji Hamada discusses a pot with Bernard Leach

Shoji Hamada discusses a pot with Bernard Leach

Had it not been for the extraordinary influence of the great potter Shoji Hamada, they may well have been. Born in 1894, Hamada studied at the Tokyo Institute of Technology before later meeting the British studio potter Bernard Leach and the critic and philosopher Soetsu Yanagi at an exhibition of Leach’s work in the city. Hamada had been one of a mere handful of pupils at the Tokyo Institute to have shown real interest in the past kilns of Japan. In an evening spent discussing the importance of handcraft, he and Leach quickly discovered a shared ideology.

After spending 3 years with Leach in St Ives, England, while Leach established his own pottery, Hamada returned to Japan in 1923 intent on building a workshop in Mashiko, a small village 60 miles north of Tokyo, where he would produce pots according to the folk-craft principles of the newly-formed mingei movement.

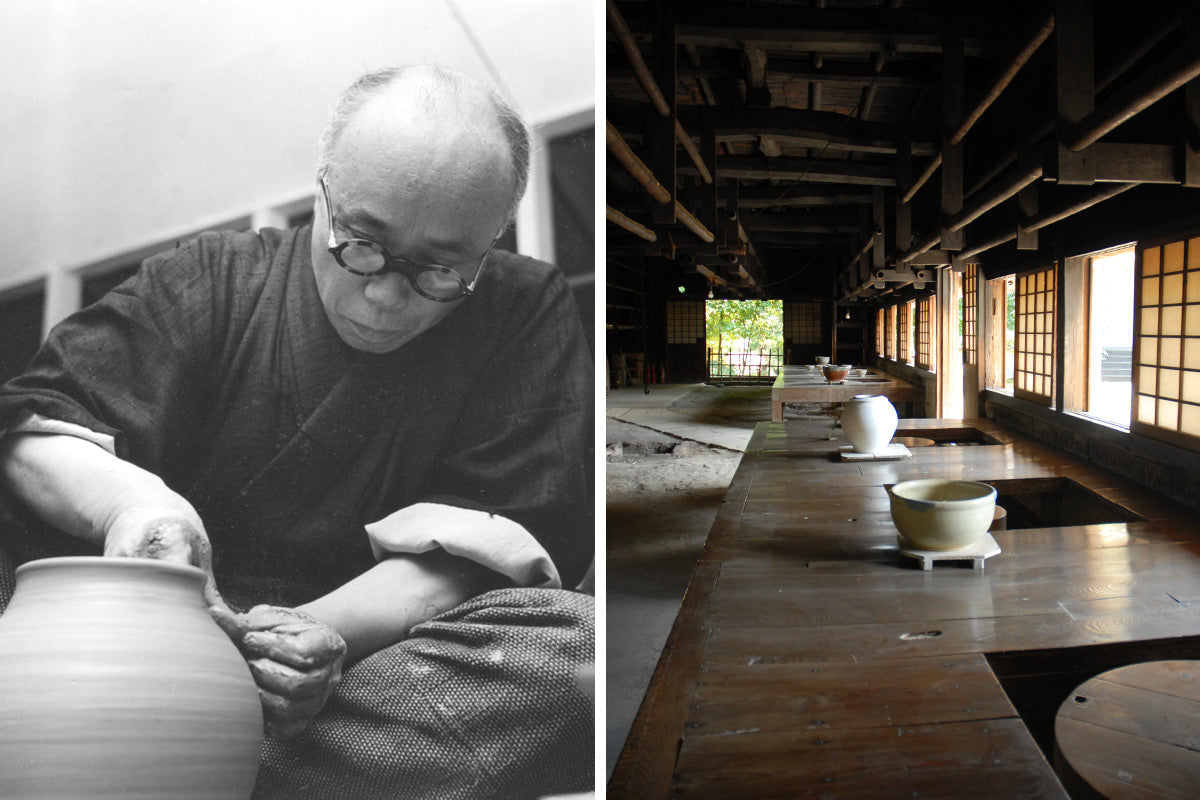

(left) Hamada throwing a small vase; (right) throwing wheels in Hamada's Mashiko workshop, now a cultural museum

(left) Hamada throwing a small vase; (right) throwing wheels in Hamada's Mashiko workshop, now a cultural museum

Mingei - meaning ‘folk arts’ – was the term coined by Yanagi to convey the essence of this emerging focus on the 'old ways' of making. It incorporated a whole raft of values that stressed the importance of a potter's locality, their working with natural resources sourced close to their workshop, and that their work - produced in anonymity, without mark or stamp - should ultimately be made for the masses to be used inexpensively in their daily lives.

the Hamada name lives on in the work by his son, Shinsaku (salt glaze yunomis) and grandson, Tomoo (salt glaze bowl), both working from Mashiko

the Hamada name lives on in the work by his son, Shinsaku (salt glaze yunomis) and grandson, Tomoo (salt glaze bowl), both working from Mashiko

Built on these utilitarian values, the mingei philosophy became a powerful driving force in tempting Japanese potters to return to their roots and the dormant old kilns. In part, the movement originated in and was sustained by the response to the brutal slaughter experienced throughout the First and Second World Wars.

In the early 1900s, all hopes were pinned on the future possibilities of industrial processes and the development of new machines. But after the indelible images of international mechanised warfare imprinted themselves on the public conscience, handmade pottery became one of a number of crafts through which it was believed society could reaffirm its humanity.

Shino chawan by Ken Matsuzaki

Shino chawan by Ken Matsuzaki

The Momoyama period (the latter half of the 15th century), particularly revered by historians for the quality of its wares and the first instances of Shino pottery, became the focal point for many makers who sought to revive the glazes, clay bodies and firing techniques of the past. As Hamada became ever more popular, his reputation gaining not just in Japan but overseas in Britain and the United States, more and more potters took up his challenge.

Mashiko, alongside older and more established kilns, quickly became a hotbed of ceramic production, and images of Hamada touring abroad in traditional garb or throwing long-established forms on his stick wheel soon garnered him a legendary status. His work, characterised by supremely proportioned forms and natural brushwork, was highly sought after, and by 1955 he had been designated a Living National Treasure.

three lidded boxes by Shinsaku Hamada

three lidded boxes by Shinsaku Hamada

But despite Hamada's immense success in perpetuating the principles of mingei, with which he had become virtually synonymous, his work never fully conformed to the values of the movement. Though he seldom stamped his pots (a fact counterfeiters have exploited for the last 50 years), nonetheless they featured in major exhibitions and were sold for significant amounts of money to wealthy customers.

As influential as mingei was in stimulating a rediscovery of traditional techniques, and as attractive as its intellectual, ethical and aesthetic ideas seemed, many potters seduced by the movement needed more. Creatively, the mingei philosophy was a dead-end; for those potters who had set their sights on making art, its dictums ultimately had to be left behind.

Oribe ware pots by Ken Matsuzaki (above) and Ryotaro Kato handled dish (below)

Oribe ware pots by Ken Matsuzaki (above) and Ryotaro Kato handled dish (below)

Since the time of Hamada's great renaissance, modern Japanese ceramics has explored and enriched the space between these worlds - between age-old crafts and the folk-art ethos and the freedom of experimentation and expression. For today's Japanese potters, tradition is understood not as the veneration of ashes but the passing on of the flame.

an emerald green Oribe vase by Ken Matsuzaki

an emerald green Oribe vase by Ken Matsuzaki

That flame now fires kilns that were at their height of production some 500 years ago, creating wares with the same tools and techniques but with a modern understanding and vision. Ken Matsuzaki, apprenticed to Shimaoka, the favoured apprentice of Hamada, continues to work from his forefathers' Mashiko village but produces pots that bear little resemblance to the vessels of these past makers, save for their dynamic energy and their conviction of form.

chawans by Bizen-ware potter Koichiro Isezaki

chawans by Bizen-ware potter Koichiro Isezaki

Koichiro Isezaki, himself the son of current Living National Treasure Jun Isezaki, produces Bizen ware pots that channel the celebrations of pure clay and fire shared by his anagama kiln ancestors but which escape homage and pastiche through their torn edges and dramatic carving.

(above) chawan by Koichiro Isezaki; (below) Ame glaze teapot and yunomis by Masaaki Shibata

(above) chawan by Koichiro Isezaki; (below) Ame glaze teapot and yunomis by Masaaki Shibata

These are just two potters from a long list of contemporaries - Masaaki Shibata, Kazuya Furutani, Tomoo Hamada, amongst many others - who have maintained the methods of the past while imbuing their ceramics with an awareness of the present.

reflections of the natural world in a square mizusashi by Ken Matsuzaki

reflections of the natural world in a square mizusashi by Ken Matsuzaki

Though the true history of Japanese ceramics is long and complex, fraught with political details and illuminated by a host of other important factors, what remains in these potters works, what was held at the core of Hamada's pots and the mingei legacy, what can be found in the great pots of the Momoyama years and extends right back to those first mud bowls of the Jomon period, is a profound appreciation for the natural world.

(above) large and small Yohen vases by Ken Matsuzaki; (below) another large Yohen vase by Matsuzaki

(above) large and small Yohen vases by Ken Matsuzaki; (below) another large Yohen vase by Matsuzaki

Instilled in Japanese pottery throughout the ages has been an understanding of the spirituality of the material world that can be traced back to the earthly Shinto deities that inhabit every natural element: rivers, rocks, forests and mountains.

Pots, formed from earth, shaped with water, and hardened with fire and air, are elemental in every sense of the word. And though the Shinto religion of today may occupy a very different space in Japan's public sphere, this fact - the specialness of all things natural and belonging to the earth - seems not to have escaped this country's people.

This is the thread that unites Japanese ceramics, from its birth thousands of years ago to the kilns still firing today. And it is this connection that will continue to engage and inspire the potters of future generations.