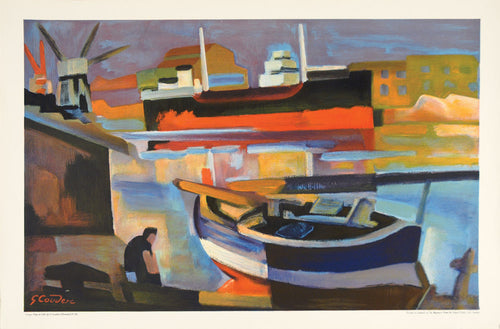

The writer and editor Raymond Mortimer first coined the term ‘Neo-Romantic’ in 1942, defining it, somewhat succinctly, as an ‘expression of an identification with nature’ that he saw common to a number of British artists of the 1930s and early ‘40s. The term is, as it was then, as nebulous as the artistic style it described, for the Neo-Romantics were no organised band or militant collective driven by a single course. The catalogue of artists to whom the label has since been applied reads like a jumbled dictionary of pre-Pop British greats:Graham Sutherland, John Piper, Paul Nash, Keith Vaughan, Michael Rothenstein – the list goes on. Though they certainly shared an affinity with landscape and the natural world, through which they described the swirling emotional storm of the interwar period, the sheer breadth of styles and technical approaches between them could hardly make a coherent movement.

'Untitled C', lithograph by Graham Sutherland, one of the first pioneers of Neo-Romanticism

'Untitled C', lithograph by Graham Sutherland, one of the first pioneers of Neo-Romanticism

If anything, Neo-Romanticism represented not a union of artists nor an art theory but an intense, intimate, spiritual way of seeing the world, developed from their visionary forebears and amalgamating disparate elements from the 20th century’s great Modernist movements. The continuity of that vision across so many diverse artists demonstrates just how deeply the Neo-Romantic influence penetrated British art, and the lasting impact it had on those who continued to paint in the tradition even throughout the politicised years of the 1960s and beyond.

'Rock Pyramid', Pembrokeshire sketch by Sutherland

'Rock Pyramid', Pembrokeshire sketch by Sutherland

In the dazed aftermath of the First World War, the British art world remained unsure how to react. On the continent, it had led to an explosion of artistic developments, perhaps most prominently the rise of Dada and Surrealism, whose deconstruction of the human psyche came as a clear reaction to the fragmentary effect the war had inflicted both physically on the landscape and metaphorically on society. But in Britain, there was no distinct parallel or alternative. Surrealism failed to capture British artists, perhaps – as Brian Catling has suggested – because there is already eccentricism innate to the British character, from our idiomatic language to our ironic and absurdist sense of humour.

'Garden Pond', engraving by Paul Nash

'Garden Pond', engraving by Paul Nash

Instead, as their name suggests, the early Neo-Romantics – namely Sutherland and Nash - began by looking back to the original Romantics themselves – to the ‘Ancients’ William Blake, Samuel Palmer, and Edward Calvert. In mythic images of Arcadian shepherds strolling through woods and camping at moonlight, Blake and his cohort had emphasised the sublimity of Mother Nature, her all-encompassing awesomeness in contrast to flawed man. The metaphor must have seemed terribly apt amid the mechanised and industrialised carnage of the war, and so the Neo-Romantics once more turned to the landscape for answers.

rare engraving by Nash

rare engraving by Nash

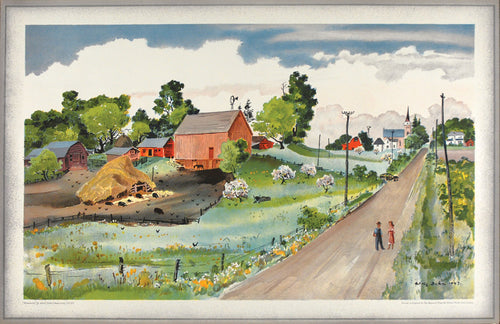

In relocating Romanticism to the very changed world of the 20th century, there was undoubtedly an element of self-delusion to the early Neo-Romantic ideal. Before the print market fell through after the Wall Street Crash and the economic depression of the early 1930s, Sutherland and Nash were making etchings and engravings of the provincial English countryside - idyllic rustic barns, ramshackle sheds and kissing gates, farmers picking wheat in the fields. Envisioning a rural life that traced its roots back to Palmer's etchings of bucolic sheep fields under moonlight, or Blake's illustrations to Virgil's Georgics, there was little concern here for social realism, for depicting the reality of post-war rural existence.

(top) 'Moeris and Galatea', etching by Palmer; (bottom) 'Sluice Gate' by Sutherland, demonstrating the Visionary influence

(top) 'Moeris and Galatea', etching by Palmer; (bottom) 'Sluice Gate' by Sutherland, demonstrating the Visionary influence

The pastoral world they were reimagining no longer existed – and had not for quite some time. Gone was the local farmhand, his face framed by a floppy hat and sweat-sodden calico shirt, ploughing the fields with oxen or shire horse. By the early 1920s he had been replaced by the tractor and, sure enough, these new machines were soon assimilated as powerful symbols within the Neo-Romantic vernacular, with artists like Rothenstein and Kenneth Rowntree celebrating the colliding of natural and mechanical worlds in rust-red tractors scraping through soil or dragging hunks of felled timber.

'Tractor and Plough', oil on canvas by Michael Rothenstein

'Tractor and Plough', oil on canvas by Michael Rothenstein

In their early pastiches of Blake and Palmer’s work, the Neo-Romantics had sought out an idealised version of landscape into which they could escape, denying the awful events and consequences of the Great War. But as these artists began to develop their own, individual styles, they revitalised their Romanticism, reflecting in images of rolling Welsh mountains and scattered patchwork fields the ominous portents of the coming Second World War and the economic and political unease that anticipated it.

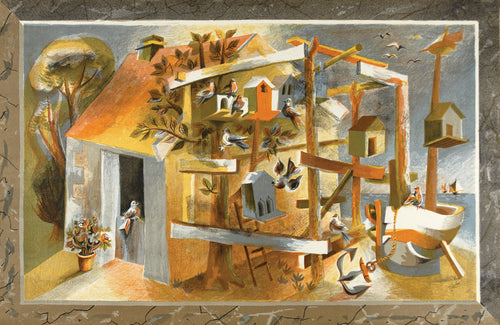

untitled lithograph by Robert Colquhoun, fusing figurative and landscape imagery into one

untitled lithograph by Robert Colquhoun, fusing figurative and landscape imagery into one

Though its proponents were by no means merely landscapists – indeed, artists such as Michael Ayrton and the Roberts Colquhoun and MacBryde put forward a powerful Neo-Romantic statement in their sinewy, elongated figures – it was in landscapes, more than anything, that the Neo-Romantics developed their vision. Their aesthetic centred around introspection, delving into rich, rural tableaux in an attempt to find something deeper, something indicative, perhaps, of the human condition.

'Landscape with Juniper', extraordinarily detailed etching by Anthony Gross

'Landscape with Juniper', extraordinarily detailed etching by Anthony Gross

Dr Peter Wakelin, in his introductory essay on the McDowall collection of Neo-Romantic art, writes of how its artists, ‘looked two ways – across the Channel to Picasso, Ernst, Dix and others, and back to Turner, Blake, Palmer and the life and landscapes of the British Isles.’ Just as the Neo-Romantics were looking forward as well as back, from the Ancients to the avant-garde, they looked inwardly as well as outwardly, reconciling the physical, visual reality of landscape – its earthiness, its greenery, geology, and topography, and its hot, sprawling urban spaces too – with the artist’s emotional, imaginative response. ‘The unknown is just as real as the known’, remarked Sutherland, ‘and must be made to look so.

'Pyramid on a Foreshore', Pembrokeshire sketch by Sutherland

'Pyramid on a Foreshore', Pembrokeshire sketch by Sutherland

Their approach was not faithful in the sense of strict, realistic representation. Rather, it centred on the idea of the genius loci - the 'spirit of place' - that imbued any given range of peaks, or fields, woodlands and coastal stretches. Like the Expressionists before them, they sought in the landscape a mirror to reflect their own emotional experience of place. Their images of pastures, hedgerows, hilltops and copses are pregnant with anthropomorphic emotions and pathetic fallacy: dark clouds roll angrily about bulging hills, fields melt or burn in refulgent Fauvist oranges, reds and virulent greens. A favourite technique was to play with scale, such that it became impossible to tell whether the writhing, biomorphic forms one could see were details of plants, roots and undergrowth blown up for the naked eye or vast swathes of countryside churned and twisted through deliberate distortions of form.

'Three Headed Rock', lithograph by Sutherland

'Three Headed Rock', lithograph by Sutherland

This animism of landscape, in which even dead trees, withered shrubs and unmoving stones seem to possess a living, breathing spirit, naturally brought out deeper, more personal resonances from its artists: the contorted thorn formations of Sutherland’s later work, for example, that show a pained attempt to understand the suffering of his Christ; or John Minton’s half-moons, full of youthful mystery and a hint of tortured madness.

'Thorn Structure', lithograph by Sutherland

'Thorn Structure', lithograph by Sutherland

The personal element of Neo-Romanticism is worth stressing. Though it may seem obvious to say that an artist’s work is one of self-expression, this was especially and consciously the case with these artists, for whom individuality and identity were more important than stylistic creed or code. There was no Neo-Romantic manifesto, no one collective identity to which artists found themselves drawn nor which they fought to defend in print. By comparison, a great many of the early 20th century’s ‘isms’, its most vociferous movements, were predicated on some form of intellectualism. Surrealists turned to Freud and Jung, to automatic poetry, psychology, a kind of cryptic and macabre surgery of the mind. Abstraction in its many reincarnations – from Vorticism and Futurism to Mondrian’s grids, Malevich’s black square, and the much later ‘action painting’ of 1950s New York – was inextricably connected to theory, be it the spiritual purism of geometry or the desire to construct images from outside our immediate visual realm.

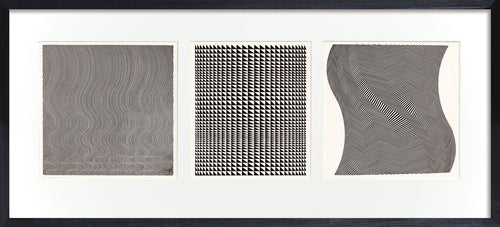

'Britanny Beach', gouache collage by John Piper revealing a strong abstract influence

'Britanny Beach', gouache collage by John Piper revealing a strong abstract influence

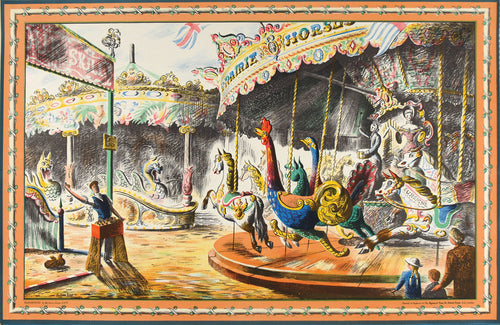

There was no such theory to Neo-Romanticism, no doctrine to which its artists adhered. It was a movement – insomuch as it could be called a movement - as easily defined by what it wasn’t as what it was: never strictly abstract, though abstraction of form was key to Keith Vaughan’s quilt-like townscapes and Sutherland’s bristling sketches of Pembrokeshire; neither silly nor sexualised enough for Surrealism, and yet greatly informed by its sense of poetic strangeness, as in the musical work of Ceri Richards.

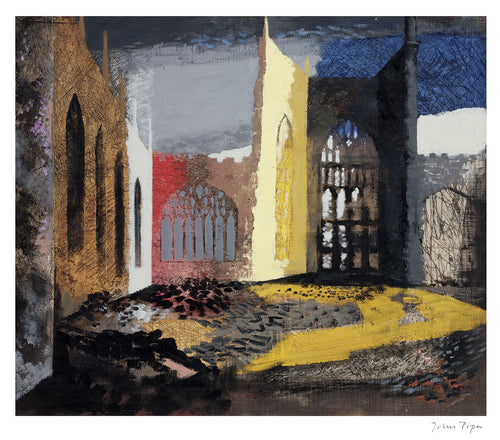

'Kilcolman Castle', oil on board by Rigby Graham

'Kilcolman Castle', oil on board by Rigby Graham

In truth, there has been little else like it in the modern history of British art – and Neo-Romanticism was an overwhelmingly British response, finding little favour in Europe or America during the post-war years when Abstract Expressionism reigned king. It remains perhaps the least celebrated and yet most pervasive influence of 20th century art in this country. Even a momentary glance at the work it produced reveals a treasure trove of extraordinary, undiscovered gems.