Over 17,000 years ago in the labyrinthine caves at Lascaux, southwest France, Paleolithic humans made some of the earliest stencils known to mankind. Placing their hands up against the cave walls, the underground dwellers would blow pigment through reeds to create outlined patterns of fingers and palms. The stencilling technique has remained in our creative arsenal for tens of thousands of years, from those basic first cave paintings to the modern day screen print. But it was in the now-abandoned pochoir process, which emerged in Paris in the late 1800s and flourished for 30 years before its decline, that the art of the stencil was pushed to the very limits of printmaking.

Bacchanale - Pablo Picasso

Bacchanale - Pablo Picasso

In concept, pochoir is a relatively straightforward form of reproduction: ink is brushed through a series of pre-cut stencils, each stencil representing a new layer of the image, until the final picture is complete. Predominantly used to recreate paintings and watercolours in remarkably truthful imitations, it also offered a flexible way to add colour to already existing black and white prints, such as lithographs, etchings, or engravings.

Femmes en Prière Devant le Soleil - Joan Miró

Femmes en Prière Devant le Soleil - Joan Miró

The power of pochoir, and likewise the source of its many problems, was its emphasis on hand-colouring. Unlike traditional techniques of printing colour, in which different inks were added directly to a plate or block and imprinted on a sheet by the press, with pochoir colour was added straight onto the paper by hand, giving the craftsman total control of the way in which his ink could be applied. With large numbers of stencils, exceptionally complex images could be facsimiled with comparative ease, while more simple prints benefitted from greater depths and breadths of tone in their colouring.

pochoir costume designs by Sonia Delaunay

pochoir costume designs by Sonia Delaunay

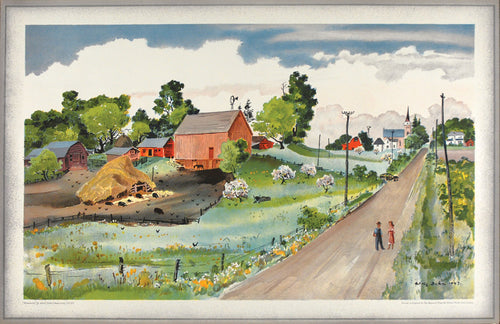

Entirely unmechanised, pochoir was both an intensive and highly luxurious way of producing images, one which suited perfectly the elegance and extravagance of the Art Nouveau and Deco fashion journals that were the source of its enormous popularity from the early 1900s to the glistening Jazz age. Artist-cum-designers, such as George Barbier and Sonia Delaunay, published their costume and textile designs in rich, luminescent pochoir folios, lending a lavish air of the haute couture to each new illustration, while everyone from bespoke furniture and wallpaper producers to high-end architects produced catalogues of exorbitantly expensive products for their endlessly wealthy clients.

(above) pochoir costumes by George Barbier; (below) fashion designs by Sonia Delaunay

(above) pochoir costumes by George Barbier; (below) fashion designs by Sonia Delaunay

The quality and complexity of each pochoir print was limited only to the skill and experience of its craftsmen. They began by analysing the composition to be reproduced, observing the number and range of colours used within the original. The image would then be broken down into a number of stencils – between eight and fifteen for the more basic, and upwards of forty for the especially detailed – cut by hand by a découpeur. Using an extremely sharp straight-edged knife, each stencil would be cut from a material of the atelier’s choice – originally aluminium, zinc, or copper, though later plastics and celluloid were used – from a minutely thin sheet approximately a tenth of a millimetre thick.

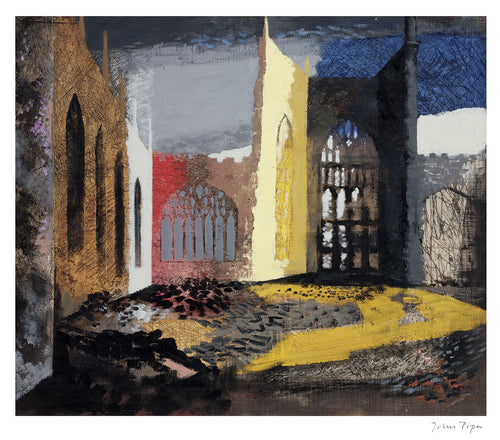

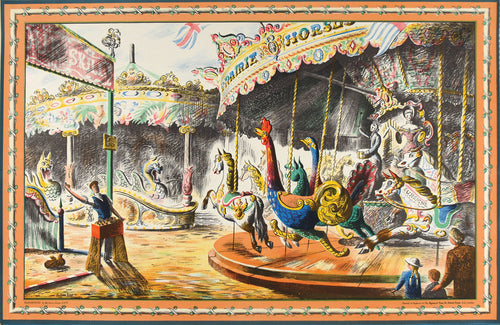

pochoir town scenes by Maurice Utrillo

pochoir town scenes by Maurice Utrillo

The stencils were then handed over to the coloristes, expert craftsmen who would apply watercolour ink or gouache through each layer with a variety of soft and coarse brushes. Using a range of pressures alongside the countless techniques available to them, from daubing to swiping, spraying, and spattering, almost any application and gradation of paint could be imitated with near faultless fidelity. As the brushed ink would settle briefly against the sides of the stencil, each pochoir print would also be left with a slightly raised, textured print surface, discernible to the eye and to the touch.

Joueur de diaule et nu - Pablo Picasso

Joueur de diaule et nu - Pablo Picasso

Of the many ateliers that specialised in the medium, none could match that of Daniel Jacomet for the quality of his finish, the breadth of projects he undertook, and the pre-eminence of the artists with whom he worked. Combining the manual processes of pochoir with the precision of collotype – a print process that accurately reproduces images by shining light through a photographic negative onto a plate prepared with a light-sensitive surface – Jacomet’s workshop could faithfully reproduce almost any work possible, even if it meant subjecting his enduring apprentices to as many as sixty individual stencils for a single image.

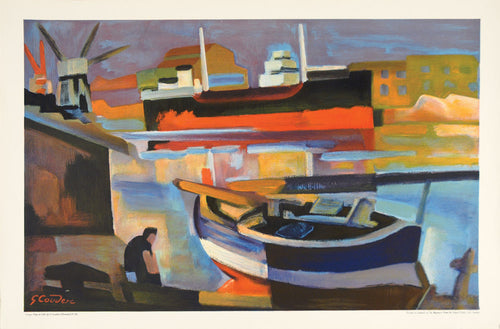

Baigneurs et Baigneuses - after Paul Cézanne, printed by the renowned Jacomet atelier

Baigneurs et Baigneuses - after Paul Cézanne, printed by the renowned Jacomet atelier

Over the years Jacomet worked directly alongside some of 20th century’s greatest artists – Dufy, Chagall, Picasso, and Miró, to name but a few – as well as producing exquisite portfolios after the works of past masters, such as his renowned suite of facsimiles of watercolours by Cézanne. Few other printmakers, let alone pochoir specialists, could lay claim to as many successful collaborations with such high-profile artists.

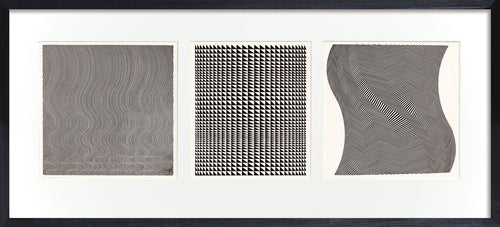

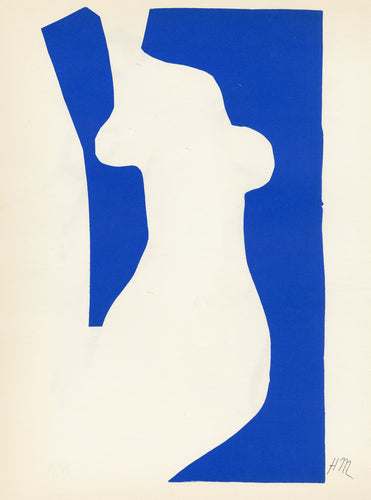

abstract pochoir designs by Jean Dewasne (left) and Alfred Reth (right)

abstract pochoir designs by Jean Dewasne (left) and Alfred Reth (right)

Eventually, the pochoir process met its inevitable end as the mechanisation of printmaking and the leaps in technology made manual production prohibitively expensive. The greatest traits of pochoir printing – the uniqueness of each image in its manual execution, the depth of its colour and the quality of its surface – were the result of its greatest weaknesses as a means of printmaking: its dependence on large numbers of highly-trained staff; its extremely time and labour-intensive methods; the great expense of its materials.

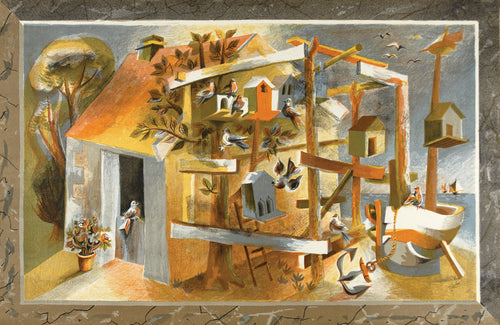

pochoir sketches after Raoul Dufy (above) and 'Personnage et Oiseaux' by Joan Miró (below)

pochoir sketches after Raoul Dufy (above) and 'Personnage et Oiseaux' by Joan Miró (below)

In its heyday, hundreds of workshops were devoted to making pochoir prints in Paris alone. Today, only Jacomet’s atelier has survived: a shadow of its extraordinary former self – demand is not high for such work – nonetheless, it remains a relic of a bygone age in which craft and art combined to create astonishing feats of printmaking. As the art world comes to value more and more the images typical of this period – Dufy’s extravagant days at the races; Delaunay’s avant-garde designs, far ahead of their time – perhaps more courageous studios will dare to take up the stencil once again.