A World of Joyful Violence

Michael Rothenstein was just four years old when his father, William – then an acclaimed painter and portraitist – removed his family of six from Hampstead to an austere farmhouse in the Stroud Valley. Surrounded by the sights, sounds and smells of a new world, Rothenstein – an ambitious artist-to-be – came armed with the appropriate tools to capture these foundational images and experiences: boxes of cedar pencils, sharpened to a spear-point; stubby wax crayons in dog-eared paper jackets; chalks ground to pinchable nubs. French pastels could be crumbled between finger and thumb, like pigment smeared straight onto the page. But it was the muddying of fresh watercolour paints that revealed to him the endless possibilities of colour: ‘curious grubby red and violet browns, dirty green, contrasted perhaps, with a single scream of pink or flame… I had a large tin of artists’ colours which, once moistened, were invitingly juicy; most of all the brilliant warm ones, orange, cadmium yellow, and vermilion.’

Michael Rothenstein in his studio

There was no shortage of inspiration to be found in the objects of his father’s collection, bringing colour to the walls of the otherwise spartan house. A series of Indian miniatures, amassed on Rothenstein senior’s recent travels, particularly affected him, as he later recalled with the critic Mel Gooding: ‘It was this element of violence, strange and dramatic happenings, in this tiny world of the miniature, and always in these very violent colours – black hills, gods and goddesses with purple and deep scarlet faces and arms, extraordinary birds flitting in and out of branches of black trees, laden with orange fruit.’

He soon found that in his own drawings, inanimate toy soldiers, engaged in silent, static battles, could be brought vividly to life. This was, as he remembered it, a full body activity. Guttural, automatic sounds accompanied frantic scribbling – ‘A lot of growling and crouching when you drew lions: the noise of jabs and slashes, with ouches of pain, when you were doing battle scenes.’ But most of all, his abiding memory was of that vermilion paint that gave life to his fierce and boyish imagination:

‘At the battle-scene phase I needed so much red, for blood – in splashes, drips and pools – that this colour was always used up first in the paint box… Whether drawing a snapping fish, or a Saracen whirling a sabre, I illustrated a world full of violence. The severed limbs are done with cruel exuberance, joyful cruelty. Yet no childhood was ever more untroubled or closer to the arm of affection. My father continually appreciated my efforts and my mother took pleasure in preserving them. This situation fostered a wild exuberance in the face of nature and helped to concentrate feeling on the tiny privacies of an enclosed and peaceful life.’ In this very fervent imagination, the symbols and the psychology of the outside world soon cross-fertilised with private play. The plumage of tin soldier’s helmets and their blazoned shields began to resemble the ornate peacockery of birds native and more exotic. Green demons with bloodied scimitars and whirling ‘Red’ Indians – inspired by a Native American costume gifted to his older brother, John, replete with feathered headdress and corded tassels – he drew scrapping with Tommies and Teutons. Knights held a particular mystique, ‘screwed up inside steel plates’ like the carapaced beetles and caddis-worms he admired by the banks of a nearby river. Meanwhile, hundreds of miles away, his father, William, painting the ruins at Ypres, was faced with the realities of war firsthand. In his own pictures of abandoned buildings, attenuated reds, pinks and brickish browns suggested the invisible human cost behind the scenes before him. ‘Over a battlefield,’ he wrote, ‘where the hopes and fears and passions of thousands of men were concentrated, a strange atmosphere of awe seems to hang. Throughout the desolation of war there is a pattern of austere beauty, and the human drama associated with war gives to this beauty a religious character … I felt as a pilgrim visiting sacred sites.’

Childhood pencil drawing with watercolour, c.1912-17, published in 1986 by Redstone Press

In his son’s hands, red was swiftly becoming at once an emblem of the terrific ripeness and fertility of his nearby environment, and an omen of alluring danger – the kind of irresistible, almost transcendent attraction that his father had felt hanging over Belgium’s fields of death. Red seemed at once to warn and to seduce: the bursting tautness of a red berry (the kind your mother warned you not to eat), the wrinkled wattle and coxcomb, the robin’s chest, the cautionary patterns of ladybirds and red admirals, tortoiseshells, painted ladies, made all the more virulent by contrasts of brown, blue and black (a recurrent combination in Rothenstein’s later work). This uncompromising red is a colour we crave, that commands the eye: the red of bright blood on a fresh cut, the red carpet, a red rag to a bull. And this collision of violence, danger, attraction, and radiance, lies at the very red-blooded heart of Michael Rothenstein’s art.

Childhood pencil drawing with watercolour, c.1912-17, published in 1986 by Redstone Press

Red Stones

Preserved for over 70 years, Michael Rothenstein’s childhood drawings were published in a large, slim booklet in 1986 by the Redstone Press. In fact it was Redstone’s inaugural publication, the press founded by Julian, Michael’s son, who took a straight translation of their surname as its imprint. Theirs was one of many geographical German names, locating its bearers near to one of the large, red granite or sandstone boulders that occasionally neighboured Germany’s riverside towns. Some, according to local stories, were the tombs of children or princesses who had been trapped by evil witches – hence their blood-red hue.

William Rothenstein, The Princess Badroulbadour, 1908; Michael’s elder siblings, John, Betty and Rachel, serve as models

This particular branch of the Rothenstein family had lived for centuries in Grohnde, near Hamelin, where William’s Jewish forebears had kept a small but prosperous mill. Moritz, William’s father, then emigrated to Bradford in the 1860s to further his fortunes in the woollen trade, preserving his devout wife’s Hungarian-Jewish heritage under the protection of the Unitarian church. As a young boy, William fell under the spell of a local pastor before leaving to become an artist, training first at the Slade, then in the Montmartre garrets of Paris. His friend, the writer Max Beerbohm, described the prim and slightly self-serious painter who emerged from his Parisian apprenticeship as a ‘Japanese Jew with a Franco-German accent. He was foreign.’ And so his four children (of whom Michael was the youngest) grew up in a cultured home that blended Jewish intimacy, fraternity and good humour with an Anglo-Catholic love of things, relics, ritual. Christmases were thoroughly Germanic: William describes in one letter ‘a very harlequinade of a tree’ dominating the dining room, ‘with blue and red balls, and fairy dolls and monkey up-sticks and glass birds playing hide and seek with one another among the branches.’ For the impressionable young Michael here lay another pivotal childhood memory: an image of the outside world brought into the privacy of the home, profound, above all, in its outpouring of colour and light:

Michael Rothenstein, Untitled (Orange Motor Car), woodcut

‘I was simply blinded with joy. It seemed to me so beautiful, so perfectly fulfilling, an image of endless, endless happiness, and endless joy. And that idea, that concept of lights, gleaming in darkness, has really resonated through all my experience of the outside world…Of fairgrounds, the idea of coloured lights, shining out of darkness, is related to a great deal that I found very, very moving. Not only the first things you think of, the moon, or a cluster of stars, but there's something very touching about a beckoning light. A moment of human truthfulness, shining in the darkness...’

Michael Rothenstein, Christmas Tree, linocut, c. 1954

Blood and Soil

In 1920, the same year William was appointed Director of the Royal College of Art, the family sold Iles Farm, moving back to Campden Hill, Kensington. But the non-conformity of his countryside upbringing had already made a lasting impression on Michael, intent now on a career in art but with a very different vision of what that meant from his father’s cosmopolitan circle.

The young man who William now began to introduce to artist friends seemed ‘Franciscan, Tolstoyan, collarless and lean, ashamed of our possessions and of our conventionalities.’ He was impressed by a studio visit to Stanley Spencer, who described how his own ‘earthly paradise’ had been shattered by the war and he now found himself piecing it back together again. But it was a meeting with the printmaker Barnett Freedman that introduced him to the inspiring ‘proletariat’ world of printmaking, leagues apart from the high-society milieu of which his father and mother were then a part. Freedman, then practising at a Working Men’s College in Mornington Crescent, kept a studio filled with the kind of hard-edged, mechanical paraphernalia – among them architectural designs and heaps of photographs – that represented the ‘wonderful slummy London’ Michael yearned to explore.

Michael Rothenstein, Self Portrait, screenprint and woodcut, 1978

But in 1926 he was stopped in his tracks, struck down with myxoedema, a hypothyroid condition that gripped him for another 16 years. His doctor advised that he should not draw: ‘his imagination is so stirred at present that it plays him tricks.’ And though he felt little pain, the illness brought with it instead feelings of intense, prolonged, near-suicidal dread, a double, shadowed vision, and raging fear. ‘If I was left, when I was in bad shape, in a room with a carving knife,’ he told Gooding, ‘I would be completely obsessed by it, either to cut my own throat, or the throat of anybody else in the room. It was so terrible.’

Michael Rothenstein, Roman Zoo, woodcut, 1986

Without the energy to drive his own art forward, he turned instead to criticism of others. ‘He analyses my paintings,’ his father wrote to Beerbohm in September, 1934: ‘psycho-analyses me, challenges, cites, collates, chides, and corrects any constructive looseness he discovers. His mind has become a formidable one; and as he can imitate anyone, speech, gesture, accent manner, so, without books, he appears to grasp ideas. He overtops me in height, and in everything else.’

Michael Rothenstein, Black Figure (Reaching for the Sun), woodcut, 1988

For several years, Michael Rothenstein had illustrated his own imaginary battles while his father sought to establish the role of the Official War Artist at the Western Front. Now, two decades later, came a cruel irony. Near Grohnde, past the banks of the Weser up Bückeburg hill, Nazi officials marshalled the local farmers attending ‘Das Reichserntedankfest’ – a vast festival celebrating the ‘blood and soil’ of the German people. This rural pageantry represented the largest of any Nazi gathering, bigger even than the Nuremberg rallies. Wehrmacht troops performed in mock skirmishes, replete with soldiery, panzers and passing bomber planes. In displays of martial and agricultural superiority, the festival promoted the Aryan ideology of a pure-bred race on native ground – trampling over the multicultural past from which the Rothenstein family had emerged.

Red Essex

As his health began to return, Michael Rothenstein sought the countryside once more. From a family cottage in Far Oakridge, Stroud, he moved in 1941 to the artists’ commune at Great Bardfield. In the decade before, Essex itself had turned red. Five miles west of Bardfield, Conrad Noel – known as the ‘Red Vicar’ – presided over the parish in Thaxted, preaching a Christian socialist message that had begun to spread throughout the county. His determination to hang the red flag alongside the Irish tricolour and the cross of St George prompted a much-publicised feud with Cambridge students, who would steal the offending items in scuffles with Noel known as the ‘battle of the flags’.

Michael Rothenstein, Red Birds, woodcut, 1990

More broadly, the colour red had infiltrated other corners of the rural world. Rothenstein had described how the black and white geometry of the farmyard – of wooden constructions, outhouses and fences, tarred and white-washed – had made a forceful impression on his childhood art. Now a more violent irruption was occurring in fields across the country as farming of a completely different kind, bolstered by industry and new mechanical machinery, took place. Several miles away, in deepest Essex, British Ford established their headquarters and factory lines. New petrol tractors, with their distinct red cast iron wheels, could be easily spotted on the horizon of ploughed fields. Two make their appearance in Rothenstein’s 1947 School Print, Timber Felling, operated by a gang of Stakhanovite workers, the red-star heart of dismembered logs echoing the wheels of the machines behind them.

Michael Rothenstein, Timber Felling, School Print series, lithograph, 1946

William Rothenstein did not see the end of the Second World War, dying in February 1945. Nor did he witness the extraordinary, chrysalis-like transformation of his youngest son’s art, from Neo-Romantic painter to experimental printmaker; from Cezanne-esque oil and watercolour landscapes to rich, coarse descriptions of rural life, in all its fantastically ugly splendour; owls and turkeys and berry-bearing trees, in wood and linoleum cuts, to a growing abstract symbology, an embrace of photographic material and cultural refuse, to screenprinting’s capacity for immediate analogy and juxtaposition – a merry-go-drawings which continued to resonate, seven decades later. He was then living in Stisted, his work caught between urban and rural scenes: Blakeian underworlds – dive cafes and tube station dioramas – and the lost Eden of the country backyard, where flourished his recognisably exotic birds. Most were round of exploratory technique-busting and metamorphing subject matter over forty years.

Michael Rothenstein, Butterflies I, woodcut, 1982

His love of this vibrant cadmium red remained at the heart of this work. But from the early 1980s especially, in the last decade of Rothenstein’s life, he made a specific return to those early childhood woodcuts, and all were cut with a very un-urbane urgency and nerve, a compressed energy, like the grain of the wood itself, which he called its ‘graph of energy’, pressed tight and thick in on itself and threatening to split. As Mel Gooding pointed out, there were deep, psychic correspondences between his method and the worlds he depicted: the way a city grows outward, for example, like the rings of a tree trunk, or how a split in the grain might mirror a river carving through the city.

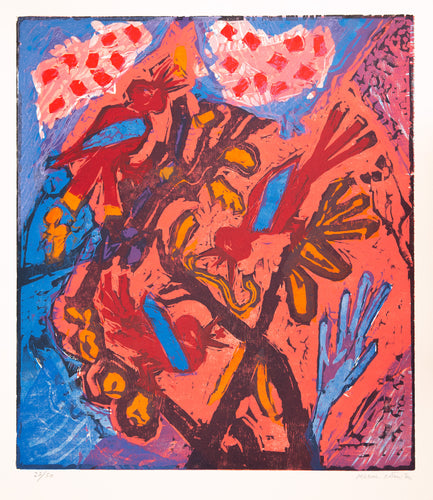

Colours collide and splash like fireworks in these late prints: red crashes into orange, violet, yellow, green. Many involved Romanesque borders that required a complex jig-sawing of multiple blocks of wood, colours overlapping like light scattered through stained glass. Ann Westley and then Anna Elinson worked as assistants in these later years, printing on the Columbian press that is now housed in the Goldmark Atelier, under the aegis of its crimson eagle counterweight. A frequent refrain, among the remembrances of all his studio hands, was of Rothenstein’s creative impulsiveness, his impatience with the technical side of things, his untameable desire to change, alter, jump in at any moment – an utterly un-repetitive approach to a medium that was supposed to embody routine, embracing mistakes at every turn.

Michael Rothenstein, Red Berries, woodcut, 1992

At the heart of it lay a fascination with the violent fertility of the natural world – ‘a pleasurable reverence’, as he later put it, ‘in co-operating with an object that was in fact torn from the very heart of nature.’ The critic Peter Fuller put it even more simply: ‘Those butterflies and birds, of the new woodcuts – they have flown out of the Paradise of your infancy.’

This article, along with many others, is featured in the Goldmark Magazine, Issue 34. Click here to view and buy >