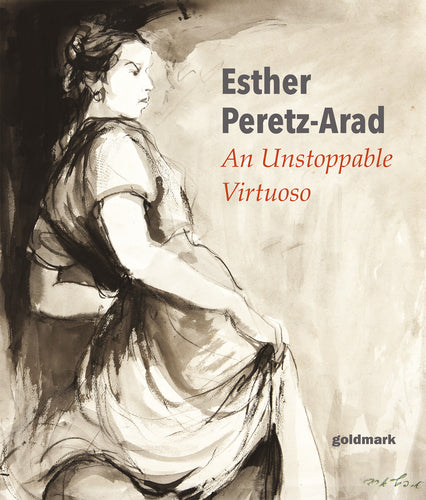

As the Goldmark Gallery unearths the forgotten treasures left behind by Esther Peretz-Arad, the Bulgaria-born Israeli artist continues to surprise. Writer Francesca Peacock turns our focus to Peretz-Arad’s etched work – where she finds a world of fairytale strangeness and dark, Gothic visions...

Esther Peretz-Arad, Abstract Composition, collage

In January 1959 – eleven years after the state of Israel had been formally declared – a new home for Israeli contemporary art and culture opened. The Helena Rubinstein Pavilion was the intended new space for the Tel Aviv Museum of Art, the gallery which was then based in Dizengoff House: the former home of the Zionist leader Meir Dizengoff, and the place where the 1948 Israeli Declaration of Independence had been signed.

The Helena Rubenstein building was to be a new, modernist, purpose-built space for the growing collection – designed by the architects Zeev Rechter, Yaakov Rechter, and Dov Karmi along the lines of rationality, clean lines, and minimal superfluity. And although the gallery would soon out-grow the new space, for a moment in the late 50s and 60s the pavilion was a centre of new artistic endeavour, and artists attempting to depict and shape the new culture they found themselves in.

Who, then, were the first artists hosted in the space? The big names of Israeli culture? The artists of the ‘Canaanite Movement’ like Itzhak Danziger, and his famous sculpture Nimrod (1939)? Or what about the artists of the burgeoning Israeli avant-garde, like the titan of Israeli modernism and abstraction Joseph Zaritsky, or the thick, impasto works of Yehezkel Streichman?

Esther Peretz-Arad, Bird at the Window, etching

One of the first solo exhibitions held in the space was something rather different. From June to July 1959, any visitor to the Helena Rubinstein pavilion would not be met with modernist abstraction, or bold new works from the avant-garde. Instead, the artist Esther Peretz-Arad had no fewer than fifty works on show. A mix of oil paintings, lithographs, and drawings; works that were figurative, romantic, and emotional. Her oil paintings depict figures in naturalistic landscapes or settings – nudes; children with kites; people kissing – and quickly spill over into the bleakly narrative: one of the works is entitled Little Girl Behind Bars, and another Deserted Village. Her young women sitting, staring, sewing, or nude were wildly different to the abstraction of the ‘New Horizons’ group of artists, or the bright paint and strokes of the ‘Land of Israel’ style of art.

Who was this artist, who had managed to stage an exhibition so at odds with the concerns and practices of the Tel Aviv artistic elite? And why has she now been all-but forgotten – both in Israel and abroad?

Esther Peretz-Arad was born in Bulgaria in 1921, and was bought by her parents to Tel Aviv (then a part of Mandatory Palestine) when she was three. They lived in the Shapira Quarter of the city; one of the newest, and most diverse areas, and full of recent immigrants fleeing the pogroms and violence of Europe. The Peretz family were poor in their new home, despite the promise and excitement of Zionism. As the Israeli writer Benjamin Tammuz put it in an essay about Peretz-Arad, ‘the innocents who had walked thousands of miles to bask in the glory of their leader do not fare well in the land where their dreams are to be realised.’ Esther, aged sixteen, had to find a way to fund her own artistic training: from 1938 onwards, she studied with the artist Aaron Avni, and cleaned his studio in lieu of payment. When speaking to Esther’s son, the architect, designer, and Royal Academician Ron Arad, he describes this as something more than a choice; it was necessary. ‘As other people breathe, she drew.’

Esther Peretz-Arad, Kite Flying, etching & aquatint

Her education continued under Avni – her ‘wondrous youth, in the stormy years of little Tel Aviv’, wrote Peretz-Arad. She met other artists; went to concerts and the theatre – and the influence of Avni’s style of figurative painting hovers behind much of her later work. In an autobiographical essay, she marks this influence out as a decision. Whilst ‘many students’ went to study with the new painters, Streichman and Avigdor Stematsky, she stayed – less for artistic reasons, than a ‘wish not to hurt Avni’. But this was far from the only life-long influence she gained from this period: in the loose huddle of creatives who met in and around Avni’s studio was Grisha Arad, a Viennese artist and sculptor who had only just made it out of Austria in 1938. They married in 1943, and, after both he and Esther had applied to join the union for Israeli artists and only she had been accepted, he gave up his own artistic pursuits to support her: he stretched every canvas, and looked after their sons when she left Israel to travel to Europe after the war. Her teacher, Avni, had died – and she needed to find new influences, new methods, and new ways of seeing the world.

And her solo exhibition at the Helena Rubinstein gallery was far from the only success she had in this period. She exhibited at Dizengoff House in the 1956 exhibition ‘Art in Israel’ alongside the other members of the Israel Painters and Sculptors Association. It was the first time the annual exhibition of the group was held across two spaces – the Tel Aviv Museum, and the Artist’s House space founded by the ‘New Horizons’ group; the avant-garde collection of artists, who had seceded from the Israeli Artists Association in 1948. Just as the more radical, modernist wing of the art world was beginning to co-opt the elite – and just a year later, the Israeli government would begin to commission major works from the New Horizons artists – Peretz-Arad was at the centre of this brave new world. She had one painting in the exhibition: the simply-named Musician.

And nor was she the only woman to be included in this growing art scene: her work appeared alongside the abstract, forceful works on paper by Aviva Uri, the experimental works of the German-Israeli painter Ruth Arion, and the graphic, political works of Tsilah Binder. There are too many women artists to name without only giving the most cursory descriptions of their work. But, although the newly-formed Israeli state was very much a masculine preserve, it appears the art world was, at least partially, open to female painters. And in 1956, Peretz-Arad joined the ranks of the men and women who made it furthest: she was awarded the prestigious Dizengoff Award. In the year she won it, so did Avigdor Stematsky: one of the founding fathers of Israeli abstraction.

Esther Peretz-Arad, Piper, etching & aquatint

Why then, after this success, was she so little known? I spoke to Gideon Ofrat, an Israeli art historian and curator who was taught art by Peretz-Arad when she worked in an elementary school in 1948. He credits his success in the art world to Peretz-Arad’s teaching, and stresses that she was a ‘brilliant painter’. But she ‘barely existed’ in the Israeli art scene by the 1970s and 80s; her ‘figurative, romantic, melancholy figures’ had no place in that world. When I asked him about her relationship to the avant-garde, he described the difficulty of her situation: she had ‘no chance’, ‘she was too “literary”, too sentimental for the leading artists of the time.’ Her son, Ron, expressed a similar point: ‘she fell in the mid generation’, between the initial pioneers of abstract painting, and the later forefront of conceptual art.

She did not stop drawing and painting until her death in 2005, and she worked with new ideas, forms, and materials; a talented bravery that ignored her current critical reception. Even after her death, her work continued. Her husband, Grisha, was a photographer, and they often had coll-aborated on cacophonous, surreal collages of photographs and paintings they called ‘photograms’ during her lifetime. After her death, he continued to incorporate her works into new pieces. Her granddaughter, the singer-songwriter Lail Arad, remembers an unceasing energy and dedication to her art: on visits to London, she would draw or paint whatever was around her, and she and Grisha would buy art supplies from a shop near the British Museum.

Esther Peretz-Arad, Girl Through a Window, etching & aquatint

But if her work was not appreciated by the art world in the years after her success in the 1950s, that does not mean that her pieces are not deserving of attention now. Her style – throughout her different mediums, from oil to lithographs, and collage to etchings – is marked by an unflinching realism that manages, without contradiction, to incorporate elements of the surreal, the fantastical, and the mythological. She was drawn to depicting the female figure: nude women with large, uncompromising bodies; young girls with dark, circular eyes. In almost all of these still, meditative paintings is a hint of something beyond the figurative. In other works – particularly in her etchings from the 1980s – Peretz-Arad took this turn towards near-surrealist art further. In one etching, a girl’s face is shown in profile, trapped inside the frame of a window. Her two hands – with their chiselled-thin fingers – reach beyond the frame, and into the viewer’s space. The sense of a break for freedom is made all the more disconcerting by the presence of a teardrop with an eye reflected in it: is this a moment of release, or a moment of mourning, of capture? This tension between constraint and freedom is a continual presence in her etchings. In A Girl Through a Window, a woman is shown behind bars at the centre of the page, with constituent parts of her face and body refracted in square, geometric shapes around her. Peretz-Arad’s skill at mixing the abstraction of the period with her own dedication to figurative art is impressive – and the result is undeniably, powerfully, unsettling.

Esther Peretz-Arad, Fly, etching & aquatint

There is a narrative bent to almost all of her etchings. With the ghostly-grey figure of Future Footprints the spectral, almost William Blake-like flying figure of Risen, and the muscular, struggling body of Cast Net, it is hard not to start thinking what fairy tale or story the etchings are alluding to. There is more than a hint of Paula Rego’s etchings of fairy tales and folk stories – particularly in her works depicting animals and children. Others, such as Peretz-Arad’s Woman Being Consoled or her detailed lithographs of old, wizened faces form a part of the social realism tradition. Ron Arad draws a link between his mother and the German artist Käthe Kollwitz, whose prints and paintings form a catalogue of the miseries of the lives of the working class.

Esther Peretz-Arad, Girl in Fishnet Stockings, charcoal & wash

But if Kollwitz’s focus was on the lives of the poor, Peretz-Arad’s focus was on the lives of women. She painted, drew, and etched scores of women seated or standing in the nude. The women are all of a similar shape across the decades – long torsos, broad shoulders, thick carves and thighs – and their bodies are drawn with a masterful economy of strokes. Even in the most detailed, such as 1980s drawings of Seated Woman in Pink and Woman in the Shadows, it is the women’s form and limbs which require the least amount of indication and noise. They emerge, fully formed, from their background. Throughout her drawings of women there is a tenderness and an intimacy; not an intimacy that feels hackneyed, or trapped within an old tradition of life models. One of the most arresting works on paper in the Goldmark collection is a charcoal drawing of a barefoot girl in fishnet stockings reclining into the shadows; the brightness of her white, elaborate dress or jacket reflects onto her face and lights up the paper from within.

Esther Peretz-Arad, Nurturing Mother and Child, etching & aquatint

Peretz-Arad’s etchings of nude women go beyond the domestic setting, or the scene of the life-room: she depicts naked women nursing children against a background of what appears to be the sea; or women who, like old plaster casts of ancient sculptures, are cracking and breaking at the seams of their joints, and have crows perching on their arms and shoulders. These are not just etched nudes: they are the product of the artist engaging with the surrealist tradition in a post-war, social-realist context.

But when I asked Ron Arad what his favourite aspect of his mother’s work was, it wasn’t her surrealist, fantastical work he mentioned. He chose her ‘nudes and landscapes’. His pairing is fascinating. Peretz-Arad’s watercolour and pastel paintings of villages, houses, and murky sea-wash skies are different to her nudes. There is breadth of colour in her palette, and scenes which never seem to stop moving, with pastel lines running like tributaries through them, or patches of watercolour melting and overlapping. But, in both, there is an un-mistakable sense of the artist’s presence, and her involvement, her proximity to what she was depicting. It was perhaps this quality – the sense of being in the presence of her unstoppable artist’s eye – that lead Mike Goldmark to tell Ron that the ‘quality of the work speaks for itself’ when he took on Peretz-Arad’s estate.

Esther Peretz-Arad, Night Sky, gouache & acrylic

At the end of my conversation with Ron, he turned to his mother’s political beliefs. When her parents took her from Bulgaria to Mandatory Palestine they were ‘idealistic and refugees’; they ‘were going to build a different world’. This ‘better world’ appears throughout Peretz-Arad’s work – from its tangible absence in some of her social realist pieces; to its mythological incarnations in some of her etchings; and the feminism and palpable tension between meditative peace and action in her nudes. Every Thursday Peretz-Arad would attend women’s ‘consciousness-raising’ meetings, and the house was always full of culture, debate, and discussion. Ron grew up not knowing ‘that there were people who were not artists’. This moment of ‘progressive, liberal ideas’ has been ‘lost’, laments Ron. It’s ‘scary, a disaster’, he says, and ‘it will affect culture’. His mother’s work – with all its variety, and breadth, and passion – is a testament to when these ideas were still in circulation.

Francesca Peacock is an arts and culture journalist. She has written for The Times, The Telegraph, The Spectator, The TLS, and other publications. Her first book, Pure Wit: The Revolutionary Life of Margaret Cavendish, will be published by Head of Zeus in September 2023.