Georges Scott’s Marianne – the Britannia of France - stands tall and defiant, her sword in one hand and the tricolor in the other, ragged and war-torn but aloft, nonetheless. With her bared breast and golden helm she becomes an Amazonian warrioress, her battle cry penned loud and clear in the black sky above: ‘Pour le Drapeau! Pour La Victoire!’ (‘For the Flag! For Victory!’)

Scott’s poster is just one of many thousands of designs produced during the First World War as governments looked to galvanise national production, bolster morale, conscript troops, and support industry at home during a period of unparalleled uncertainty. In the hands of master poster artists, they proved an indispensable communicative medium: mass-produced and easily disseminated, the poster brought colour and expressive resonance in its simplicity, allowing nations to remotely applaud and admonish citizens in equal measure. Reappropriated by the state at a time of hardship, the modern-day poster was born of excess; its journey from profit-making to propaganda was as conflicted as it is fascinating.

Historically, posters had been a tool for commercial, rather than political or social exhortation, persuading would-be customers (with varying degrees of subtlety) to part with their hard-earned cash. Their stratospheric rise to prominence across the 19th century can be traced back to early innovations in the field of chromolithography. Jules Chéret, grandfather of the Belle Epoque poster, had trained as a lithographer in Britain before returning to Paris to establish his own enterprise. Technological advances in printmaking equipment led Chéret to develop a brand new form of three-colour lithography, one that allowed for more faithful reproductions of colour and accurate registration between pulls of the press.

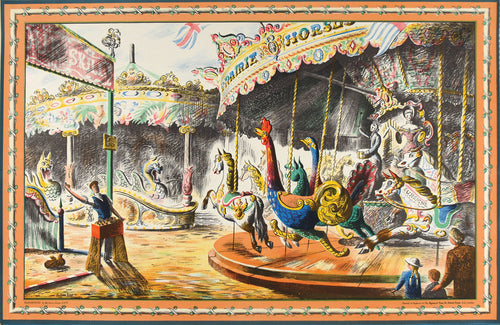

Through Chéret’s invention a riot of colour flooded into poster bills and advertising pamphlets, previously dominated by great blocks of black and white text. Their proliferation was extensive as landlords and local management began to realise the potential of advertising real estate. Before long, almost every stretch of public and private property, from street walls to scaffolding and even local monuments, was plastered with images of hedonistic pleasure and domestic bliss. Vertical space was monetised on an unprecedented scale as the avenues and alleyways of Paris, London, and New York blared out their mass of consumerist messages.

Yet by the start of the First World War, the poster was faced with its first major decline. By the mid-1900s, billboards were now in competition with a host of rival communications: magazines, fashion brochures, newly distributed broadsheets and rapid developments in film and radio. Accustomed to having only to fend off fellow competitors, with billstickers regularly scuffling over their disputed territories, the poster was now living in an age of near constant verbal and visual assault, where single voices found it increasingly difficult to rise above the clamour of newspaper adverts or the excitement of the wireless.

For the wartime poster, this competition became curiously paradoxical. In the past, posters had created and been driven by a frenzy of consumption as manufacturers of alcohol, tobacco and chocolate goaded customers with images of lavish indulgence. But at a time of war, with countries burdened with crippling debts, scant resources, and national rationing, this was exactly the kind of profligate behaviour governments sought to repress. In a bizarre, ironic turn of events, the poster was now forced to fight and undermine the very world of urges from which it had fed and thrived.

Sponsored images preyed alternately on citizens' guilt, fear, and nationalistic duty to scrimp and save, or to turn over their purchasing power to the state through war bonds and ‘liberty loans’. Walls that once bore multifariously diverse messages demanding customers’ attentions were now replaced with posters conjuring a sense of collective conscience, reiterated through repeated calls to arms and aid: ‘Join now!’; ‘Sign up!’; ‘Your country needs YOU.

This astonishing transformation from commercial tool to national broadcast was accompanied by an observable change in tone. Bringing high-quality art by established artists to the streets had seen the poster both championed and challenged as a kind of class equaliser, with boulevards hailed as the ‘poor man’s picture gallery’ or ‘frescos of the crowd’. With the emergence of magazines and radio, it was often in poorer districts that the poster was at its most effective, where residents would have limited access to new and expensive forms of media.

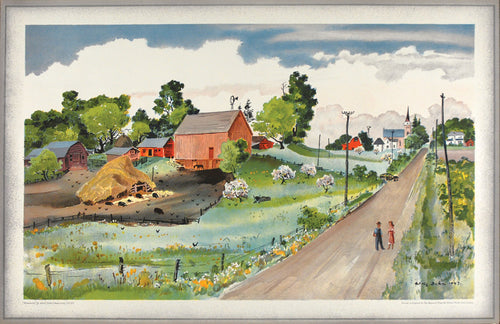

Previously, businesses had played to working class aspirations, presenting their mundane products, such as soap bars or bleaches, with a whiff of middleclass luxury. Now, in the midst of war, it was to these same people that governments looked to aid production or join the conflict, but their appeal was to a very different kind of sentiment. Illusions of extravagance are abandoned in favour of ordinary young soldiers, fresh-faced and square-jawed, or generically wholesome, down-to-earth scenes of families left behind to support those at the front through agricultural and manufacturing programmes. Jules-Abel Faivre’s bright-eyed young conscript, unkempt and unshaven, his hand held aloft with the cry ‘on les aura!’ (‘we’ll get them!’), could be any mother’s son, any wife’s husband or girlfriend’s beau; universality was key to the wartime poster, in which depth and breadth of reach was paramount in sustaining the war effort both at home and abroad.

Unsurprisingly, though common themes recur within the many posters produced in America, Britain, Germany and France, there were notable divergences in approach too. While German propaganda posters were characterised by a comparable sobriety, their clean-cut designs far closer in feel to the large woodcut advertisements produced on the continent before Chéret’s lithographic innovations, French and British posters seemed to employ a far broader palette.

In France, where the demands of war had been especially economically damaging, the message was clear and singular: ‘Souscrivez à l’Emprunt National!’ (‘Subscribe to the National Defence Loan’). Though intended to encourage the sale of war debts, its emotive, patriotic language of ‘signing up’ evidently struck a chord, contributing to sizeable increases in the number of new recruits.

Meanwhile in Britain, enlistment, fund-raising, and arms production remained primary concerns: Frank Brangwyn’s ‘Mars Appeals to Vulcan's cleverly recasts a virile munitions worker as the Roman god of ironsmiths, his hammer in hand, visited by a deified soldier in the garb of his brother, the war god Mars. Though the ministry of defence was unafraid of shaming their male populace into enrolment, broader appeals sought to equate support at home with that at the front. Brangwyn’s invocation of the Roman family pantheon was just one of many designs to bring soldiers and civilians together and emphasise a collaborative sense of pride and responsibility.

Faced with the colossal task of mobilising populations in the preparations for war, it’s no surprise that nation states looked to the poster as a means of engaging the masses. Elizabeth Guffey, writer and historian of poster art, describes how, ‘at a time when steak was hard to come by and fresh bread meant long lines…citizens were asked to give everything – their loyalty, their faith and their money.

The incredible explosion of poster production some fifty years earlier, followed swiftly by condemnation from hard-line critics and fetishisation by the collectors who pulled bills from walls before their paste had even dried, proved that the poster was a form of communication capable of prompting strong emotional responses in a wide and varied audience. Those few examples that have weathered the hundred years or more since their design and display now represent a rich contextual source, images as powerful and moving to those mindful of the conflict as they were to those who eventually took part in it. Saved from the destructive fate assigned to most, these survivors silently proclaim their message even today, relics of an extraordinary age of printmaking in times of extreme adversity.