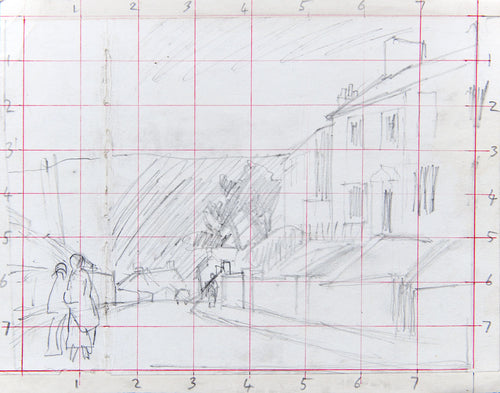

George Chapman liked to work alone. Parked up in a residential road – ‘I don’t get out unless it is absolutely necessary’ – he would paint and even etch from the confines of his car, canvas or steel plate propped up against the steering wheel. On occasion, inquisitive children tapping on the window or persistent old dears with trays of over-stewed tea – strong enough, he once remarked, to use as etcher’s acid - would force the artist to reluctantly roll down the window. Some even made it into the paintings themselves: ghostly figures caught on the fringes of Chapman’s vision, their hazy faces and huddled coats trudging by on the pavement as the painter looks out through the centre of the road to the industrial estates beyond. But at heart, he was a recluse: ‘I remember the story about Turner who, when out painting with friends, disappeared into a ditch so that no one could see what he was doing. I am exactly the same and want, if possible, total detachment.

'God Save the Queen', oil on board

'God Save the Queen', oil on board

The invocation of Turner is an intriguing one. Like Turner, Chapman was primarily a landscape painter, with a Romantic spirit and a touch of the anti-fashionable about him. As painters, both focused their eye outwards to the middle distance – for Turner, to ships caught in churning vortexes, for Chapman, to the intersecting lines of houses and streets, telegraph poles and coalmine smokestacks: ‘In looking at the houses directly in line with the eye, I deliberately lose the substantiality of the people and objects closest to me; clarity is accorded only to the material which particularly interests me; the remainder is allowed to lose itself in a kind of mist.

(above) engraving by JMW Turner; (below) 'The Bridge', etching and aquatint

(above) engraving by JMW Turner; (below) 'The Bridge', etching and aquatint

But unlike Turner, for whom nature was sublime, pastoral and picturesque, Chapman’s world was one of post-industrialisation, of pit-heads and coal trains. If Turner was the painter of light – brilliant, shimmering, incandescent light – Chapman’s work is as matter-of-factly filthy as it gets. His beautifully honest paintings and prints of the Rhondda reveal a hearty Welsh community in the grips of a smoggy chokehold. The black soot of smoke and coke, coal, colliery and bitumen spreads across his canvases and hard-ground etchings.

'Children Going Home from School'

'Children Going Home from School'

When he arrived in Wales in 1953, he was just one of a small number of British artists – including L. S. Lowry and the ‘Kitchen Sink’ painters Derrick Greaves and John Bratby – who found solace not in rolling hills or sweeping coastlines but industrial landscapes, dusty interiors, and the working classes. Over a period of almost forty years painting the south Wales valleys and their mining towns he produced what is perhaps the single greatest and most complete record of Welsh coalmining communities of any artist. He was as alone in his choice of subject and his enduring dedication to it as he was in his self-imposed, car-bound solitude.

'Pigeon Huts', etching from the 'Rhondda' suite

'Pigeon Huts', etching from the 'Rhondda' suite

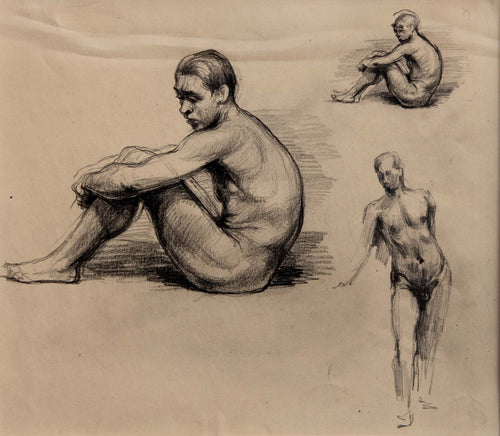

In truth, he had not sought out the Rhondda, but rather stumbled upon it almost by accident. He began his art career as a commercial designer in 1928, producing posters for London Transport and Shell alongside John Nash, Graham Sutherland, John Piper and Barnett Freedman. Though it paid well, he found the world of graphics dull and uninspiring and by 1937 had enrolled at the Slade School of Art, only to transfer after a year to the Royal College of Art under Freedman’s advice. His early heroes were Walter Sickert and the Camden Town Group, then the social realism of the Euston Road Group in the late 1930s. After the Second World War, he found work as a teacher in a number of London art schools, having moved his young family to Great Bardfield in Essex where he joined the artists Edward Bawden and Eric Ravilious, Michael Rothenstein, and Kenneth Rowntree who had made the village their own artistic commune.

etching of a barn in Great Bardfield, Essex

etching of a barn in Great Bardfield, Essex

Though Bardfield soon became a collaborative hotspot for its local artists, he found himself drawn away before he could cement a reputation there. In 1953, on his way back from a trip to the family holiday cottage in Cardiganshire, he decided to drive back via a route through the Welsh mining valley towns. The experience was to change his life forever: ‘I got a fantastic shock…I realised that here I could find the material that would perhaps make me a painter at last.’ Aside from an interruption in the 1970s, Chapman would return every year to the Rhondda and its outlying districts to paint the lives of its inhabitants, either renting temporary rooms for prolonged periods of painting or making sketches to be brought back to his studio in Great Bardfield. By 1964, he had moved to Wales permanently, living in the small cottage in Aberaeron he had purchased over a decade before.

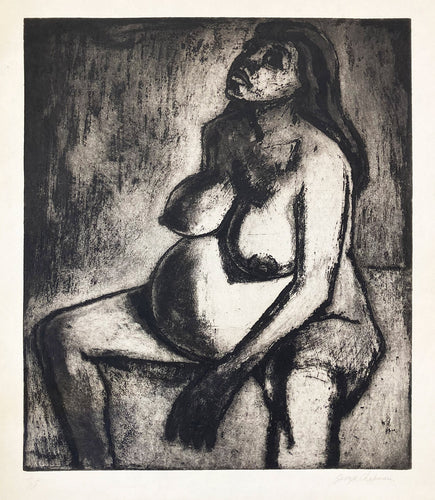

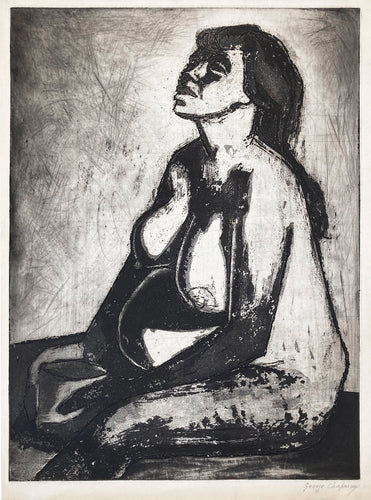

'Pregnant Woman', one of a number of etched portraits of Chapman's wife, Kate

'Pregnant Woman', one of a number of etched portraits of Chapman's wife, Kate

Stylistically, as with his subject matter, he was much his own man. Early etched portraits of his pregnant wife – thickly bitten, with a strong sense of texture and classical chiaroscuro – bear in their heavy lines and expressive quality a resemblance to Rouault. Rothenstein, who had offered access to his own press, acted as informal tutor, teaching him much about the medium and its many processes. Like his fellow Bardfield artist, Chapman relished the range of textures and surfaces the acid could bring out of the zinc plates and he soon established a distinctive etching style. He produced two major etching series – The Rhondda Suite and The Camberwell Set – in addition to numerous individual prints of dilapidated collieries and dusty street views.

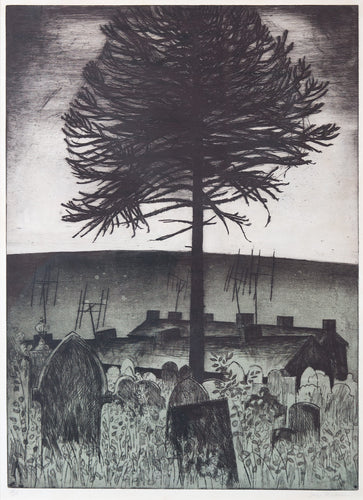

'Graveyard and Monkey Tree'

'Graveyard and Monkey Tree'

The paintings have been much lauded for their account of the social injustices suffered by the Welsh mining community, and for their subsequent decline when coal ceased to be a profitable venture. While Chapman himself claimed there was no deliberate political undercurrent to his work – ‘I have no social comment to make…My job as an artist is to take things as they are…the social comment [comes] over by itself…’ – he was certainly more than sympathetic to the often perilous conditions the miners faced day in and day out. One written recollection, entitled ‘First and Last Trip Below’, recounts Chapman’s only experience down a mining shaft: ‘I am not really interested in the hell below ground – I shall be buried soon enough. It is the humans above and how they live I want to see…The whole place was in an appalling state…Men work down there to earn a living. I thought it disgusting. Coal is cheap at any price.

two typical oils, illustrating Chapman's often preferred use of thick, textured paint

two typical oils, illustrating Chapman's often preferred use of thick, textured paint

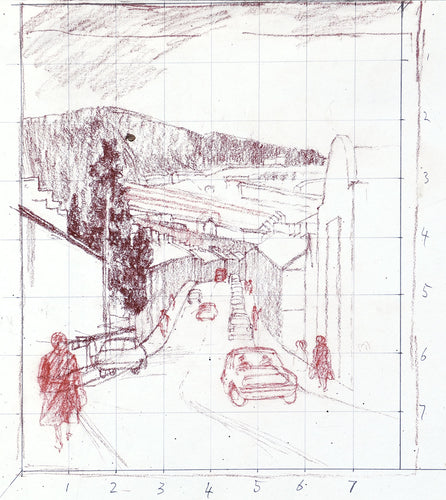

Though the human element fascinated Chapman, he was as much driven by a formal view of the world around him that sought out compositional elements in the streets and skies. He often deliberately chose scenes in which the zig-zag patterns of telephone wires, sloping rooftops, television aerials and angular trees stretch across the skyline. Another favourite technique was to reflect in the paint the peripheral blur one experiences looking down a road: curbs and pavements curve outwards, passers-by have their faces stretched and distorted or are brushed out until unrecognisable.

a powerful example of Chapman's 'peripheral' style of painting

a powerful example of Chapman's 'peripheral' style of painting

Though Chapman was an atheist, religion played a large part in these street scenes too, as described by the writer Robert Meyrick: ‘…He has often introduced striking symbolism in the cruciform shapes of the telegraph poles and railway signs of the present day. They pierce the sky to dwarf the nearby church spires and Non-Conformist chapels, symbolic of a community not only constrained by geography but also by the church.’ In the enormous six-foot canvas Work and Pleasure all three interests appear together: the gridded metal frames of pit-heads, chimneys and aerials in the distance; the figure walking by in the bottom right-hand corner, whose face fades into a swirling mass of brown paint; and the telegraph mast shaped like a giant cross that rises high into the soot-tinged air, dominating its surroundings.

'Work and Pleasure', oil on board

'Work and Pleasure', oil on board

Chapman had come to Wales to paint its mining industry and the sunken landscapes in which it was seated; but he stayed for its people, for the countless local characters who would squint through the car window at a half-finished canvas or peer over a shoulder as he sat painting in a deserted street: ‘I suddenly realised that these old mines had nothing more to say to me, that it was the present, what was going on today that was really the subject I ought to work on…’

'Camberwell Set, Motorway'

'Camberwell Set, Motorway'

Disillusioned with his own work and the art market’s obsession with Pop in the 1970s, he gave up painting for ten years only to return in 1980 and find the communities he had left behind changed almost beyond recognition. Gone were the collieries, dismantled and their concomitant equipment removed; gone too were the spidery stacks of masts and wires. More families could now afford cars themselves, parked in garage extensions and along cul-de-sac pavements, preventing kids from playing in the previously empty roads outside their houses.

'Passing Storm'

'Passing Storm'

Despite its many transformations, Chapman found in his return to the Rhondda fresh new stories to tell. He remained in his little cottage, painting the panorama of everyday Welsh rurality until his death in 1993. Unlike his earlier contemporaries, his work never found a mass audience, though this is unsurprising given he was an artist who sought not shock, nor awe, but a quiet, slow, hidden corner of the world that would have remained otherwise forgotten. Today, his output stands as an indispensable record of Welsh industrial history, one made all the more poignant for the obvious affinity between the artist and his shifting surroundings.