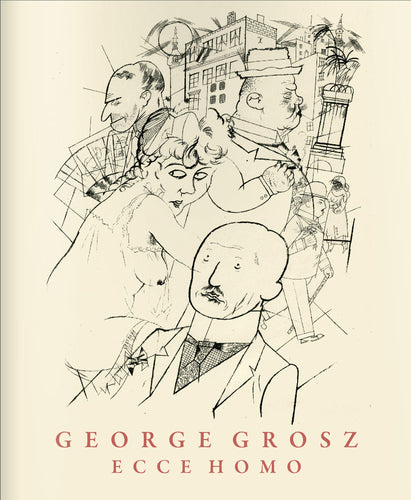

With his unforgiving style and corrosive sense of humour, George Grosz is widely recognised as one of the great German artists of the 20th century.

A major figure within the German Expressionist movement, his work has in the last few decades become increasingly sought after. To coincide with our recent acquisition of some incredibly scarce signed and hand-coloured lithographs by Grosz, we thought we'd feature him as this week's Profile artist.

the sharp, expressive lines of a George Grosz lithograph

the sharp, expressive lines of a George Grosz lithograph

George Grosz was born in Berlin and from 1909 studied art in Dresden for two years before attending the art academy in his native city. In 1913 he moved to Paris, amidst the artistic revolutions taking place in the cafes and studios of Montmartre, and started to develop the freer, cartoon-like style of drawing that was to become the hallmark of his mature work.

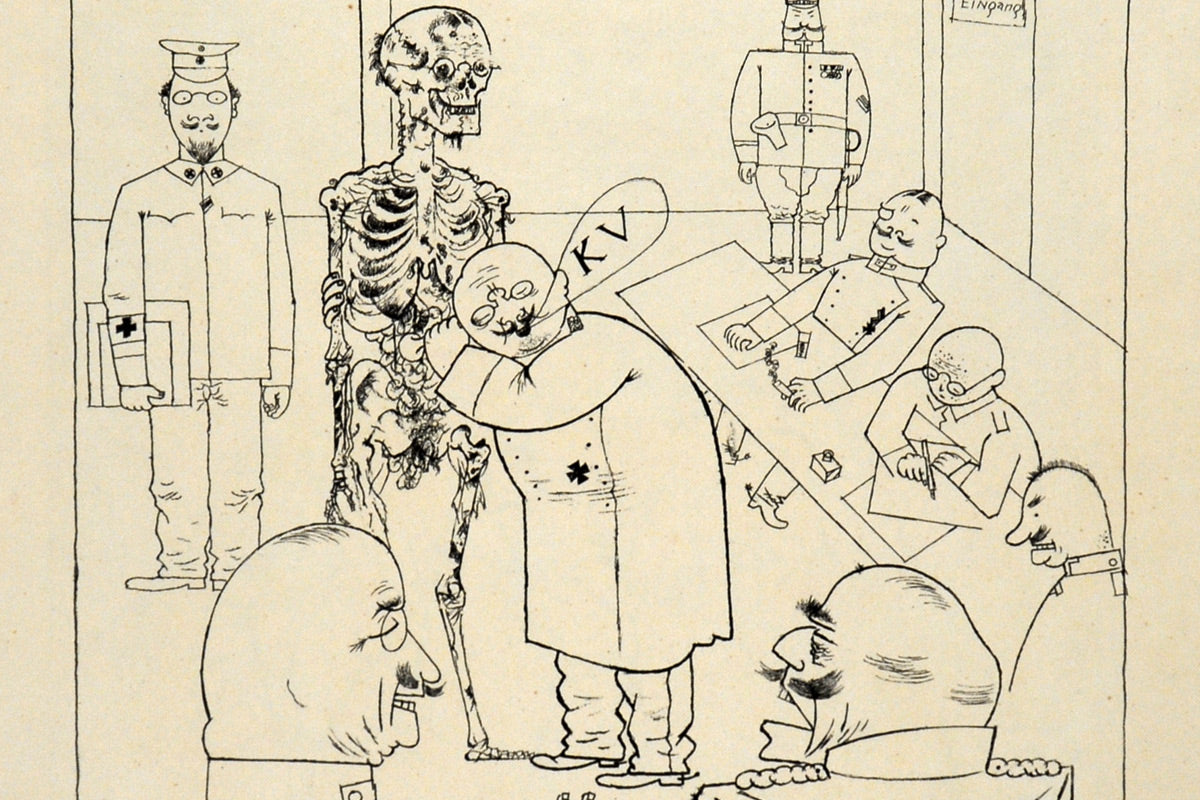

wartime slaughter watched by bureaucratic overseers - military satire in Grosz's 'Gott Mit Uns' suite

wartime slaughter watched by bureaucratic overseers - military satire in Grosz's 'Gott Mit Uns' suite

With the outbreak of the First World War, Grosz was drawn back to Germany. After initially volunteering for military service he was hospitalized and discharged in 1915, then conscripted again months later. Overwhelmed by the daily carnage, in 1917 Grosz unsuccessfully tried to commit suicide. In an act of bitter irony worthy of his own satirical images he was brought back to health under the care of a military hospital, only for the authorities to elect to execute him. Fortunately a wealthy patron, Count Kessler, was able to intervene on his behalf and the death sentence was commuted.

Grosz's wartime experiences had a long-lasting effect on his life and art

Grosz's wartime experiences had a long-lasting effect on his life and art

Grosz’s experiences during the First World War deeply affected his views about society. His political opinions became so firmly radicalized that he joined the Communist Party in protest against German militarism. His hatred of war dominates much of his work, with depictions of off-duty soldiers as brutalising thugs with Neanderthal brows or as corpulent idiots drooling at women. Grosz also joined the artists Otto Dix, Max Ernst, Kurt Schwitters and John Heartfield (amongst others) in forming the Berlin Dada group. More politically motivated than their other European counterparts, they published incendiary manifestos on the social injustices they saw in post-war Germany.

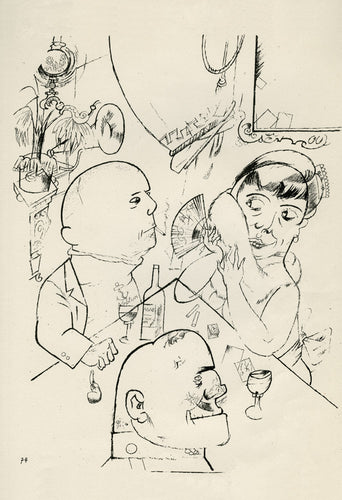

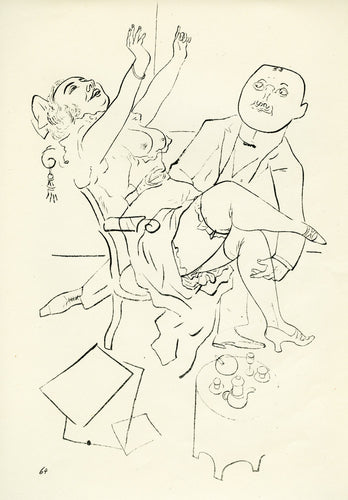

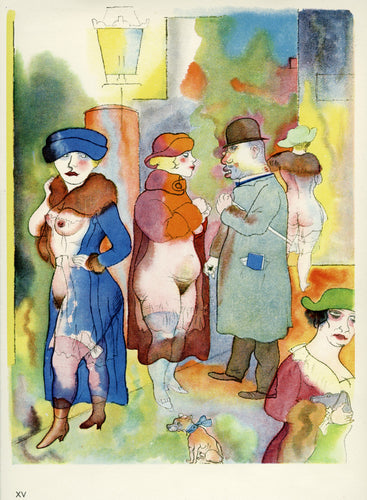

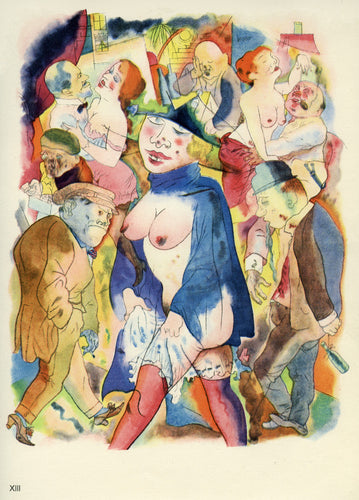

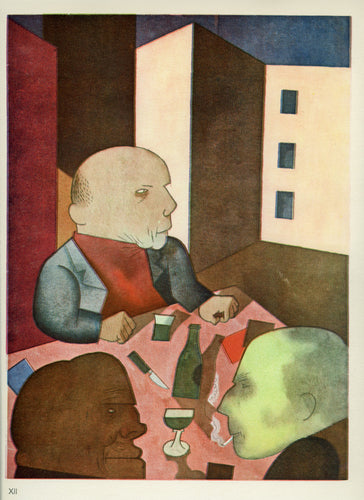

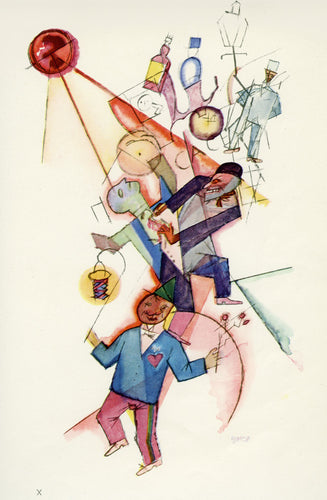

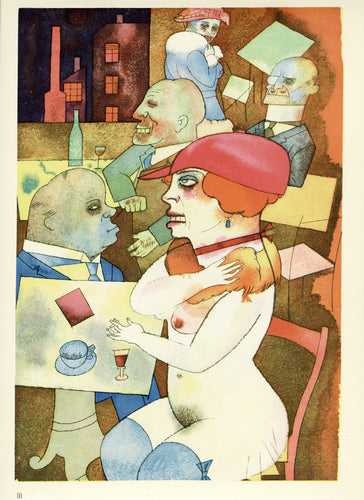

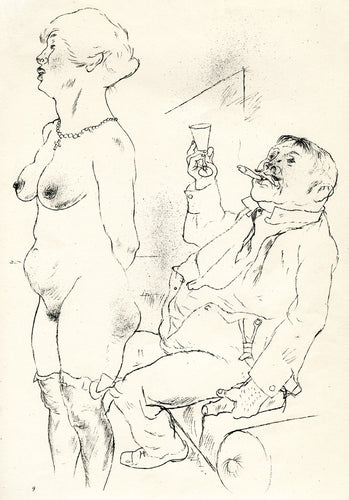

lithographic prints after Grosz's drawings: from the 'Ecce Homo' suite (above left and below) and the rare 'Munkepunke Dionysos' series (above right)

lithographic prints after Grosz's drawings: from the 'Ecce Homo' suite (above left and below) and the rare 'Munkepunke Dionysos' series (above right)

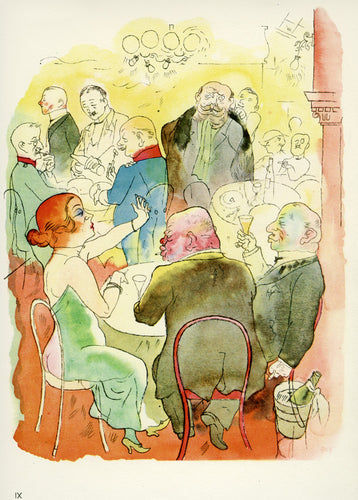

During the 1920s Grosz reputation grew when his drawings were collected together and issued as suites of lithographic prints in series such as The Face of the Ruling Class (1921) and Ecce Homo (1923). For the latter work Grosz was prosecuted for indecent representations, which offend the sense of modesty and morality of a person of normal feeling, and fined 6000 marks. In 1928 he produced lithographs after his drawings entitled Hintergrund (‘Background’) and yet again faced criminal charges for blasphemy and defamation of the German military. After prolonged court appearances drawn out over four years, he was eventually found ‘not guilty’ and escaped persecution.

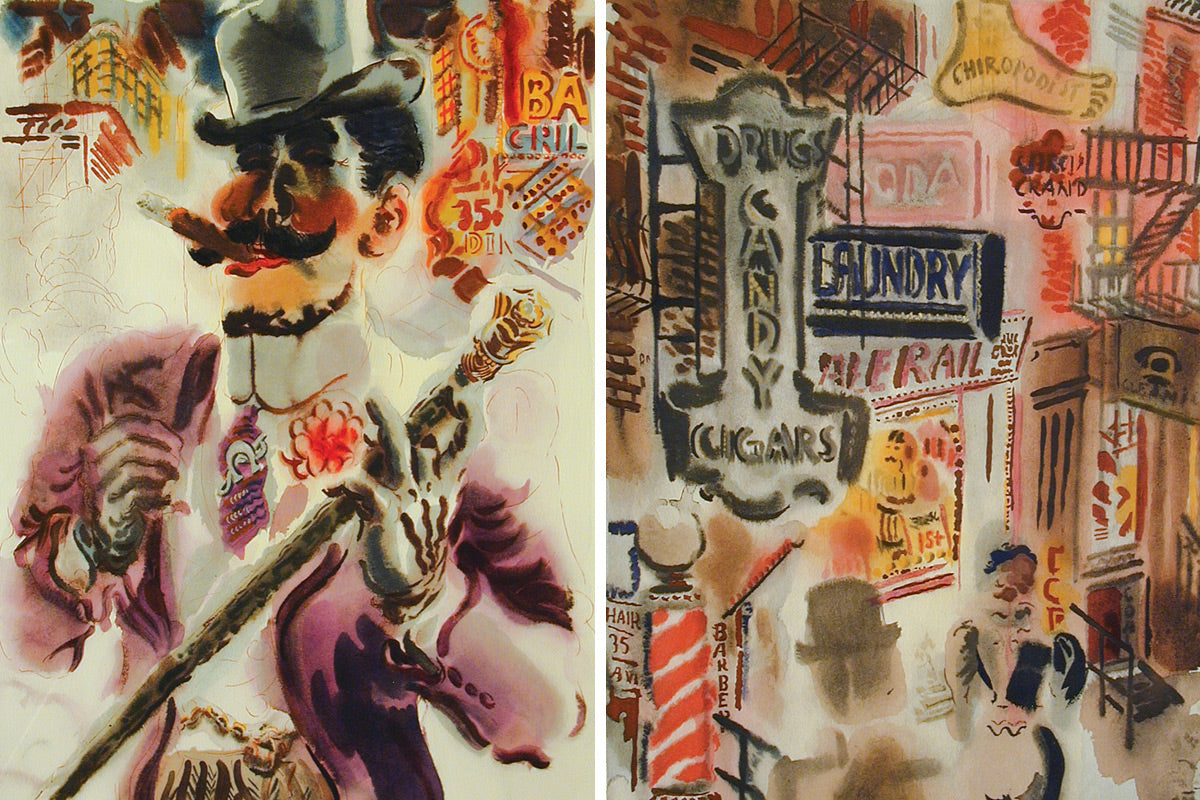

'My drawings will naturally stay true - they are fireproof...' - Grosz attacks the corruption of 1920s Berlin

'My drawings will naturally stay true - they are fireproof...' - Grosz attacks the corruption of 1920s Berlin

Grosz is regarded today as one of the greatest 20th century satirical artists. Generally his ‘targets’ were the government, wealthy businessmen and ‘high society’ bourgeoisie, but with the rising influence of Hitler and the Nazi Party they too were lampooned with equal vigour. Grosz later recalled how his contempt for much of German society was conveyed in his art: I drew and painted from a spirit of contradiction and attempted in my work to convince the world that this world is ugly, sick and mendacious.

'Filth...but Premier League filth' - Grosz's 'Munkepunke' lithographs as described by one of our customers

'Filth...but Premier League filth' - Grosz's 'Munkepunke' lithographs as described by one of our customers

Inevitably Grosz came into conflict with the authorities and in January 1933 he fled to America to settle there permanently with an invitation to teach in New York. Later that month Hitler was appointed Chancellor of Germany and the very next day SS stormtroopers smashed their way into Grosz’s studio. Four years later his work featured prominently in the so-called Degenerate Art exhibition held by the Nazis. Grosz was labelled a cultural Bolshevik while 285 of his works were removed from public collections, many of which were destroyed or later burnt at public rallies.

Grosz's work in America turned away from the overtly political but retained his strong sense of the colour and grime of city streets

Grosz's work in America turned away from the overtly political but retained his strong sense of the colour and grime of city streets

Although Grosz received widespread critical acclaim in America, he was not particularly well off financially. In order to supplement his income he taught in several art institutions and published his autobiography, A Little yes and a Big No (1946). In it he revealed what life was like amidst the hyperinflation and political mayhem of post-war Germany:

The world of the 1920s was like a boiling cauldron. We did not see those who fed the flames. However, we did feel the growing heat and watched the violent seething. There were speakers and preachers on every street corner… A real orgy of hate was brewing, and behind it all the weak Republic was scarcely discernible. An explosion was imminent.

scantily clad women and their bulging clientele are a recurring theme of the 'Ecce Homo' suite

scantily clad women and their bulging clientele are a recurring theme of the 'Ecce Homo' suite

With a final touch of irony Grosz returned to live in Berlin in June 1959 only to die there weeks later on 6th July. In 1933 he had perceptively written of his own art that, no question about it, my illustrations are among the strongest statements against this German brutality. Today they are more real than ever … and they will be shown later in ‘more humane’ times, just as the images of Goya are shown today. The powerful prints, drawings and paintings that survived the Nazi's cultural expunging continue to prove him right.