The publication of Los Caprichos marked a defining point in Goya’s career. In 1792 he developed a debilitating illness – exactly what he suffered from, no one knows – which would ultimately leave him deaf. His recuperation took over five years, during which the isolation imposed by his withdrawal and his deteriorating hearing had a profound impact on his life. He quickly became depressed – cut off from the world, quite literally, by his deafness – and feared for his sanity.

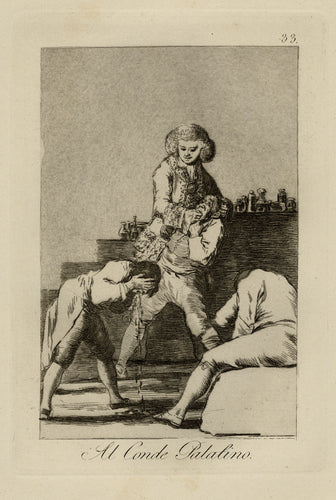

'Lo que Puede un Sastre!' ('What a tailor can do!') - 'How often can some ridiculous creature be suddenly transformed into a presumptuous coxcomb who is nothing but appears to be much. That is what can be done by the ability of a tailor and the stupidity of those who judge things by their appearance.' (Goya's commentary taken from the Museo del Prado manuscript)

Distress and anxiety expressed themselves in new subjects: witches, raping banditos, gaols and moon-lit madhouses. In his alienation he read papers on the French revolution and began to draw with a frequency and conviction he had not previously experienced. The resulting sketches, informed by the Enlightenment philosophies of Rousseau and Voltaire and his own bitter invective, would form the basis of Los Caprichos, Goya’s first major foray into etching. Unable to find a reputable publisher willing to take on the suite, the launch eventually took place in a liquor store across the road from his house. The address? No. 1, Calle del Desengaño - ‘Disillusion Street’.

'Duendecitos' ('Hobgoblins') - 'Now this is another kind of people. Happy, playful, obliging; a little greedy, fond of playing practical jokes; but they are very good-natured little men.'

'Duendecitos' ('Hobgoblins') - 'Now this is another kind of people. Happy, playful, obliging; a little greedy, fond of playing practical jokes; but they are very good-natured little men.'

You couldn’t make it up; but then, of course, that is precisely what Goya did. Like Swift’s Lilliputian buffoonery or the comical cast of Voltaire’s Candide, the characters of Goya’s Caprichos are apparitions of satirical semi-fantasy, derived from observations of Madrid’s society at large. An advertisement in the Diario de Madrid announcing the publication’s arrival in February, 1799, reiterated the fact: ‘[The author] has selected from amongst the innumerable foibles and follies to be found in any civilised society, and from the common prejudices and deceitful practices which custom, ignorance, or self-interest have made usual…Since most of the subjects depicted in this work are not real, it is not unreasonable to hope that connoisseurs will readily overlook their defects.’

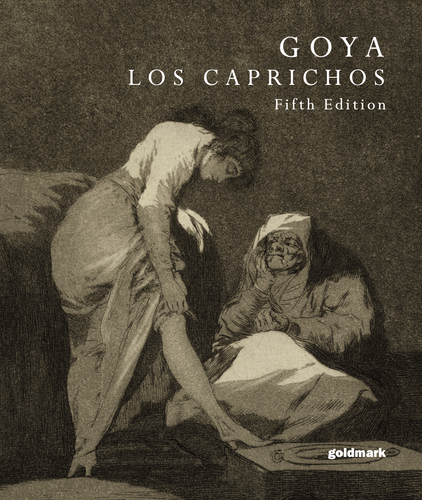

'Que Sacrificio!' ('What a Sacrifice!) - 'That's how things are! The fiancé is not very attractive, but he is rich, and at the cost of the freedom of an unhappy girl, the security of a hungry family is acquired. It is the way of the world.'

'Que Sacrificio!' ('What a Sacrifice!) - 'That's how things are! The fiancé is not very attractive, but he is rich, and at the cost of the freedom of an unhappy girl, the security of a hungry family is acquired. It is the way of the world.'

The allegorical use of a ‘dream world’ offered Goya an alibi, but anyone paying even the slightest attention to its contents could not fail to see direct parallels with Spain’s religious institutions, its bumbling aristocracy, or its viciously backward hob-goblin populace. The Caprichos present a veritable litany of behaviours vulgar and lecherous: the streets are rife with prostitution, gold-diggers, rapists and pederasts, drunkards and hooligan demons. Veiled references to the clergy equate their religious cult with witchcraft and diabolism, with old crones and Satanic goats cloaked in clerical raiment; priests glut and gorge with cannibal appetite while preaching abstinence and administering punishment.

'Mucho Hay Que Chupar' ('There is plenty to suck') - 'Those who reach eighty suck little children; those under eighteen suck grown-ups. It seems that man is born and lives to have the substance sucked out of him.'

'Mucho Hay Que Chupar' ('There is plenty to suck') - 'Those who reach eighty suck little children; those under eighteen suck grown-ups. It seems that man is born and lives to have the substance sucked out of him.'

It was savage, unflinching stuff, and Goya evidently anticipated a backlash: ‘The public is not so ignorant of the Fine Arts’, the advertisement continues, ‘that it needs to be told that the author has intended no satire of the personal defects of any specific individual in any of his compositions.’ He had invented the first modern-day disclaimer.

'Unos á Otros' ('What one does to another') - 'It is the way of the world. People jest and fight with one another. He who yesterday played the part of the bull, today plays the 'caballero en plaza'. Fortune presides over the show and allots the parts according to the inconstancy of her caprices.'

'Unos á Otros' ('What one does to another') - 'It is the way of the world. People jest and fight with one another. He who yesterday played the part of the bull, today plays the 'caballero en plaza'. Fortune presides over the show and allots the parts according to the inconstancy of her caprices.'

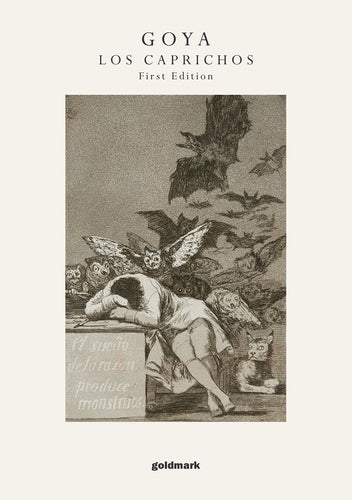

His anxiety at the Caprichos’ reception is betrayed in the shuffling of No. 43, originally the titular plate, to the very middle of the set. The artist, marked out by the stylus on his desk, sits slumped over his work, surrounded by the visitations of his own nightmares: scowling cats and whooping owls (associated not with wisdom in the Spanish tradition but brainless stupidity). Scrawled beneath the desk were the words ‘El sueño de la razon produce monstruos’ – ‘The sleep of reason produces monsters’.

'El Sueño de la Razon Produce Monstruos' ('The sleep of reason produces monsters') - 'Imagination abandoned by reason produces impossible monsters: united with her, she is the mother of the arts and the source of their wonders.'

'El Sueño de la Razon Produce Monstruos' ('The sleep of reason produces monsters') - 'Imagination abandoned by reason produces impossible monsters: united with her, she is the mother of the arts and the source of their wonders.'

The image and its caption were inspired by a title page to a 1793 edition of Rousseau’s Philosophie, whose texts were then anathema to both Crown and Church. Swapping it out for a comparatively sober self-portrait, Goya may have hoped that his reference would go unnoticed.

The frontispiece to the 1793 edition of Rousseau's 'Philosophie', a copy of which Goya may well have read during his prolonged convalescence.

The frontispiece to the 1793 edition of Rousseau's 'Philosophie', a copy of which Goya may well have read during his prolonged convalescence.

He had good reason to be wary: though the Inquisition of the late 18th century was not the same rabid outfit that had struck terror into the heart of Spanish society two-hundred years previous, when detention, torture, and summary execution were commonplace, it remained as corrupt, bullying, and rapaciously litigious as ever. If called to trial, there were few ways to indemnify against prosecution: at best, one could hope to escape with a hefty fine, confiscation of property, or brief internment; at worst, a gaol sentence, exile, or financial ruin.

'Corrección' ('Correction') - 'Without correction and censure one cannot get on in any faculty, and that of witchcraft needs uncommon talent, application, maturity, submission and docility to the advice of the great Witch who directs the seminary of Barahone.'

'Corrección' ('Correction') - 'Without correction and censure one cannot get on in any faculty, and that of witchcraft needs uncommon talent, application, maturity, submission and docility to the advice of the great Witch who directs the seminary of Barahone.'

Moreover, as court painter to King Charles IV, Goya was politically connected, and those connections may even have helped secure the suite’s production (the Caprichos were printed in studios in the attic of the French Embassy in Madrid). The last thing Goya wanted to be seen to be doing was prodding the Inquisitorial hornets’ nest.

'Nohubo Remedio' ('There's no help') - 'They are persecuting this saintly woman to death! After having signed her death sentence, they take her out in triumph. She had indeed deserved a triumph and if they do it to insult her they are wasting their time. No one can shame someone who has nothing to be ashamed of.'

'Nohubo Remedio' ('There's no help') - 'They are persecuting this saintly woman to death! After having signed her death sentence, they take her out in triumph. She had indeed deserved a triumph and if they do it to insult her they are wasting their time. No one can shame someone who has nothing to be ashamed of.'

Contemporary satire of the sort he had seen in England from Gillray and Hogarth was, by now, an established genre; thanks to the efforts of the latter, copyright of their engravings was even enshrined in law, and its authors were protected from claims of defamation. By comparison, visual satire in Spain prior to Goya was not just impracticable: it was virtually non-existent. Los Caprichos provided a watershed moment, a cultural litmus test – and one that it promptly failed.

'Aguarda que te Unten' ('Wait til you've been anointed') - 'He has been sent out on an important errand and wants to go off half-anointed. Even among the witches, some are hare-brained, impetuous, madcap, without a scrap of judgment. It's the same the world over.'

'Aguarda que te Unten' ('Wait til you've been anointed') - 'He has been sent out on an important errand and wants to go off half-anointed. Even among the witches, some are hare-brained, impetuous, madcap, without a scrap of judgment. It's the same the world over.'

The sales were pitiful: in four years just 27 copies were sold of the 300 produced. The project was a financial catastrophe of epic proportions: over 24,000 prints, plus rejected proofs, prepared and pulled over the course of a year and a half, virtually all for nothing. The King, who had taken a liking to Goya, eventually snuffed out the venture, requesting the surrender of all unsold sets and acquiring the original copper etching plates in exchange for a pension for Goya's last son, Javier.

'Si Sabrà mas el Discipulo?' ('Might not the pupil know more?') - 'One cannot say whether he knows more or less; what is certain si that the master is the most serious-looking person who could possibly be found.'

'Si Sabrà mas el Discipulo?' ('Might not the pupil know more?') - 'One cannot say whether he knows more or less; what is certain si that the master is the most serious-looking person who could possibly be found.'

Quite what had deterred putative purchasers remains unclear. There is little evidence the Inquisition had Goya in their sights; nor were copies prohibitively expensive, though it was perhaps those with the greatest means to afford a set that were most brutally lampooned in its pictures. Asses appear as a recurring metaphor for the uneducated, pretentious upper-classes, while doctors, lawyers and ministers are portrayed as quacks and charlatans. Like Trump, Goya’s vision of society is grounded in the ‘art of the deal’: brides are sold off (all marriage, to Goya, is a transaction), sex is bought, witchcraft cults practise initiation and conscription, and men and women alike are swindled and enslaved.

'Todos Caeràn' ('All will fall') - 'And those who are about to fall will not take warning from the example of those who have fallen! But nothing can be done about it: all will fall.'

'Todos Caeràn' ('All will fall') - 'And those who are about to fall will not take warning from the example of those who have fallen! But nothing can be done about it: all will fall.'

In Todos Caerán (‘All Will Fall’) human-headed birds of various ages and stations – a sword-bearing soldier, a hooded priest – circle a female decoy. Her plump breasts and delicate ringlets identify her as a prostitute, perhaps a recent new recruit: she uncomfortably avoids their gaze, resolutely facing away from her oncoming clientele. Below, two more prostitutes treat a recently captured punter to a colonic regurgitation. Already plucked of all his feathers (a common idiom throughout for paid-for-sex), he is left with nothing, spewing his empty guts onto the floor. By their side, the madame, bedecked in Goya’s familiar clerical robes, appears almost like the Mother Superior of a convent, knelt in faux-penitent prayer. It is a scene of eye-wateringly acerbic cynicism, in which no one escapes with any dignity.

'Porque Esconderlos?' ('Why hide them?') - 'The answer is easy. The reason he doesn't want to spend them and does not spend is because although he is over eighty and can't live another month, he still fears that he will live long enough to lack money. SO mistaken are the calculations of avarice.'

'Porque Esconderlos?' ('Why hide them?') - 'The answer is easy. The reason he doesn't want to spend them and does not spend is because although he is over eighty and can't live another month, he still fears that he will live long enough to lack money. SO mistaken are the calculations of avarice.'

Throughout the Caprichos, Goya is careful not to overplay his disgust. Innuendo provides the series with levity: the priest who clutches his money-bags like swollen testicles, or ‘The Shamefaced One’ (‘El Vergonzoso’), whose nose is a circumcised penis (‘it would be a good thing’, writes Goya in his explanatory notes, ‘if those who have such unfortunate and ridiculous faces were to put them in their breeches’).

'El Vergonzoso' ('The shamefaced one') - 'There are men whose faces are the most indecent parts of their whole bodies and it would be a good thing if those who have such unfortunate and ridiculous faces were to put them in their breeches.'

'El Vergonzoso' ('The shamefaced one') - 'There are men whose faces are the most indecent parts of their whole bodies and it would be a good thing if those who have such unfortunate and ridiculous faces were to put them in their breeches.'

But of all the socio-political themes at play in the Caprichos, anti-clerical imagery is the prevailing force of the suite. In Nadie nos ha visto (‘No One Has Seen Us’) the late critic Robert Hughes finds a perfect example in the priests that ‘gorge themselves, mouths opening into those voracious chasms of darkness that were for Goya, as they are for us, the most menacing emblems of an unleashed, cannibal orality, those terrifying expressions that stir the same primordial fears as the mouth of Goya’s later Saturn, tearing his child into gobbets…’ The cross-hatched apparition behind, whose hand reaches out as if to bless the cup, provides a wicked spin on Catholic transubstantiation, the communion wine that becomes the blood of Christ.

'Nadie nos ha Visto' ('No one has seen us') - 'And what does it matter if the goblins go down to the cellar and have four swigs, if they have been working all night and have left the scullery gleaming like gold?'

'Nadie nos ha Visto' ('No one has seen us') - 'And what does it matter if the goblins go down to the cellar and have four swigs, if they have been working all night and have left the scullery gleaming like gold?'

The Caprichos were not just a tour-de-force of satire: they were a suite of technical mastery too. Before their publication, the last apotheosis in the etching medium had been achieved by Rembrandt. In Rembrandt’s time, the process was still relatively straightforward: a metal plate – usually copper – is covered in a thin ‘ground’ of waxy resin which is then smoked over a flame, the soot turning the surface of the wax black. This makes it easier for the etcher to see his design, which he makes by drawing into the resin with an etcher’s needle. Where he draws, the copper under his line is laid bare.

'Obsequio á el Maestro' ('A gift for the master') - 'That is quite right; they would be ungrateful pupils not to visit their professor to whom they owe everything they know in their diabolical science.'

'Obsequio á el Maestro' ('A gift for the master') - 'That is quite right; they would be ungrateful pupils not to visit their professor to whom they owe everything they know in their diabolical science.'

The plate is then submerged in a bath of acid, where the mordant ‘bites’ the exposed lines in the copper plate. These bitten grooves will hold ink when the plate is cleaned of the ground and prepared, and the impression can be taken on a rolling press. Large areas of darkness could only be achieved through very close, dense cross-hatched lines that gave an impression of uniform blackness, but by the time Goya came to print the Caprichos a recent technological advance was available to him which allowed gradations of tone comparable to a watercolour wash.

'Se Repulen' ('They spruce themselves up') - 'This business of having long nails is so pernicious that it is forbidden even in Witchcraft.'

'Se Repulen' ('They spruce themselves up') - 'This business of having long nails is so pernicious that it is forbidden even in Witchcraft.'

This technique was called aquatint: it involved dusting fine particles of resin onto the plate, which was then heated, causing the resin to melt into a minutely pock-marked ground. Goya and his technicians were among the first in Spain to make use of it, and the results were astonishing. Figures emerge from near total blackness, lurk in the shadows, leer out in contrasts of linear sharpness and aquatint haze; at least two prints were composed wholly through aquatint, blocking out and rebiting the plates over and over again until the composition was complete – an extraordinary feat of technical printmaking.

'Buen Viage' ('Bon Voyage') - 'Where is this infernal company going, filling the air with noice in the darkness of night? If it were daytime it would be quite a different matter and gun shots would bring the whole group of them to the ground; but as it is night, no one can see them.'

'Buen Viage' ('Bon Voyage') - 'Where is this infernal company going, filling the air with noice in the darkness of night? If it were daytime it would be quite a different matter and gun shots would bring the whole group of them to the ground; but as it is night, no one can see them.'

The process would become essential to the Caprichos’ theme: Goya’s host of goblins and ghouls are creatures of the night, belonging properly to the world of dreams; aquatint plunged the series into a twilight wash of sepia. These images from a first edition set, known to have been one of the first thirty or so copies that Goya had bound, reveal the sumptuous levels of depth and perspective this new skill afforded him.

'Ya es Hora' ('It is time') - 'Then, when dawn threatens, each one goes on his way, Witches, Hobgoblins, apparitions, and phantoms. It is a good thing that these creatures do not allow themselves to be seen except by night and when it is dark! Nobody has been able to find out where they shut themselves up and hide during the day. If anyone could catch a denful of Hobgoblins and were to show it in a cage at 10 o'clock in the morning in the Puerto del Sol, he would need no other inheritance.'

'Ya es Hora' ('It is time') - 'Then, when dawn threatens, each one goes on his way, Witches, Hobgoblins, apparitions, and phantoms. It is a good thing that these creatures do not allow themselves to be seen except by night and when it is dark! Nobody has been able to find out where they shut themselves up and hide during the day. If anyone could catch a denful of Hobgoblins and were to show it in a cage at 10 o'clock in the morning in the Puerto del Sol, he would need no other inheritance.'

The term ‘caprice’ is normally redolent of fantasy and whimsical fancy, but Goya’s are as nightmarish as they come. The final, apocalyptic plate of the series – Ya Es Hora (‘It is time’) – calls the heady nocturne to its end, as witches, phantoms and howling devil-priests retreat into the night with the arrival of dawn and the ‘waking’ of Goya’s dream vision. In its savage jabbings at the moral depravity of Spanish society, its journalistic exposé of cultures of corruption and stupidity, it anticipated the modernist vigour of Dada and the wartime anger of the Expressionists, of Ernst, Grosz and Dix. To know that it was a failure on its release only reaffirms its extraordinary modern-day status as a masterpiece of near unrivalled technical and satirical expression.