Chronicler of the downtrodden and dispossessed characters of his local Shropshire haunts, John Farrington has lived a life in keeping with his own paintings. Though stylistically eclectic, his work has long retained a strong, distinctive voice quite out of kilter with contemporary trends, but suffused always with a strange melancholy that has made his work so moving.

‘What I like about this part is its rather run down & everyone looks like real people for realy in the Souse East & Tinker Belle part of England people arent quite real to me. I suppose theres not so much money about and absolutely not a bit of Fart – not a mausoleum or sketching class for 50 miles around. There was a dinner here last night for 100 farmers & freemasons husbands & wives & by 11.30 it was Bedlam, they started off very smart in long dresses & Tux & ended like a demonstration with nerve gas & broken bottles at the University of Tuscaloosa.’

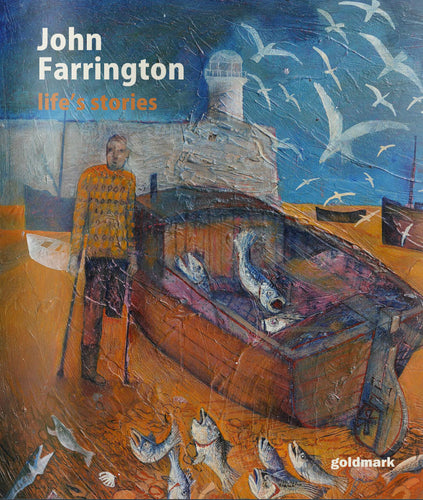

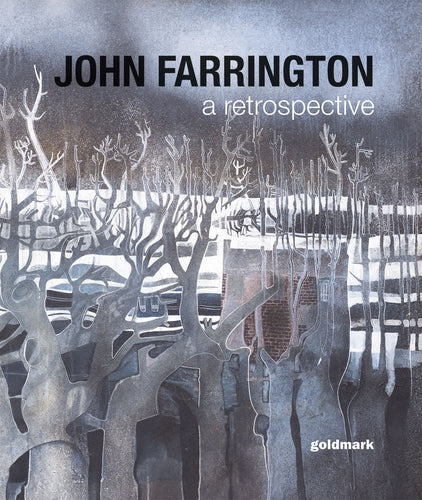

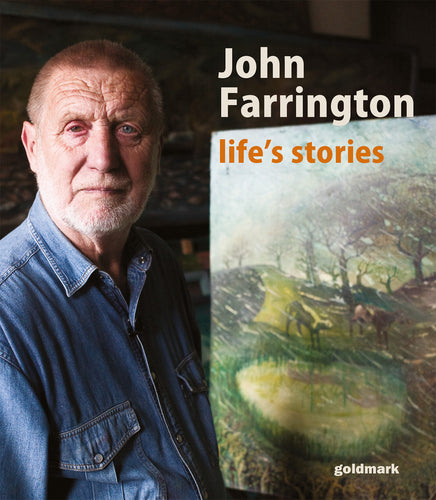

John Farrington

John Farrington

This is the artist Edward Burra, writing to his friend and fellow artist John Banting in 1970 while on holiday in the provinces. At the time, he was corresponding from a ‘gloom box’ hotel in Herefordshire, but he might as well have been describing the Shropshire haunts of John Farrington, and this farmers’ dinner, spiralling toward animal chaos, a Farrington painting.

I interviewed John Farrington some few years ago by telephone when Burra’s name cropped up. I had put to him what I thought then was a risky question – ‘if you could read this piece now, what is the one thing you would like to see written about you?’ – and his reply came back, calmly, in an instant: ‘That I’m working in a long tradition of British painters. Sutherland, John Piper, Edward Burra, the ‘Neo-Romantics’, Reynolds and the Kitchen Sink lot of course, and further back Ravilious and Edward Bawden.’

If I was taken aback by the speed, and the conviction, of his reply, it is only because Farrington’s work seems so inescapably his own – especially today, when he has had more than 70 years of working through influence into the soul of his own paintings.

He is now in his 90th year, and in those seven decades much has changed in his work. The fallow-brown, grey, and glum-green palette of those early days of Kitchen Sink influence, combined with an abstracting tendency of shapes sharp and bristling like thistles borrowed from Alan Reynolds, has given way to an extraordinary breadth of colour and surface. From the textures of those early works, the paint daubed and spread with Social Realist intent like cold margarine on toast, he has explored thick impasto and illustrative flatness. But their peculiar quality has remained the same; despite the eclecticism of his oils, watercolours, pastels and pencil drawings, you can pin them all to his name.

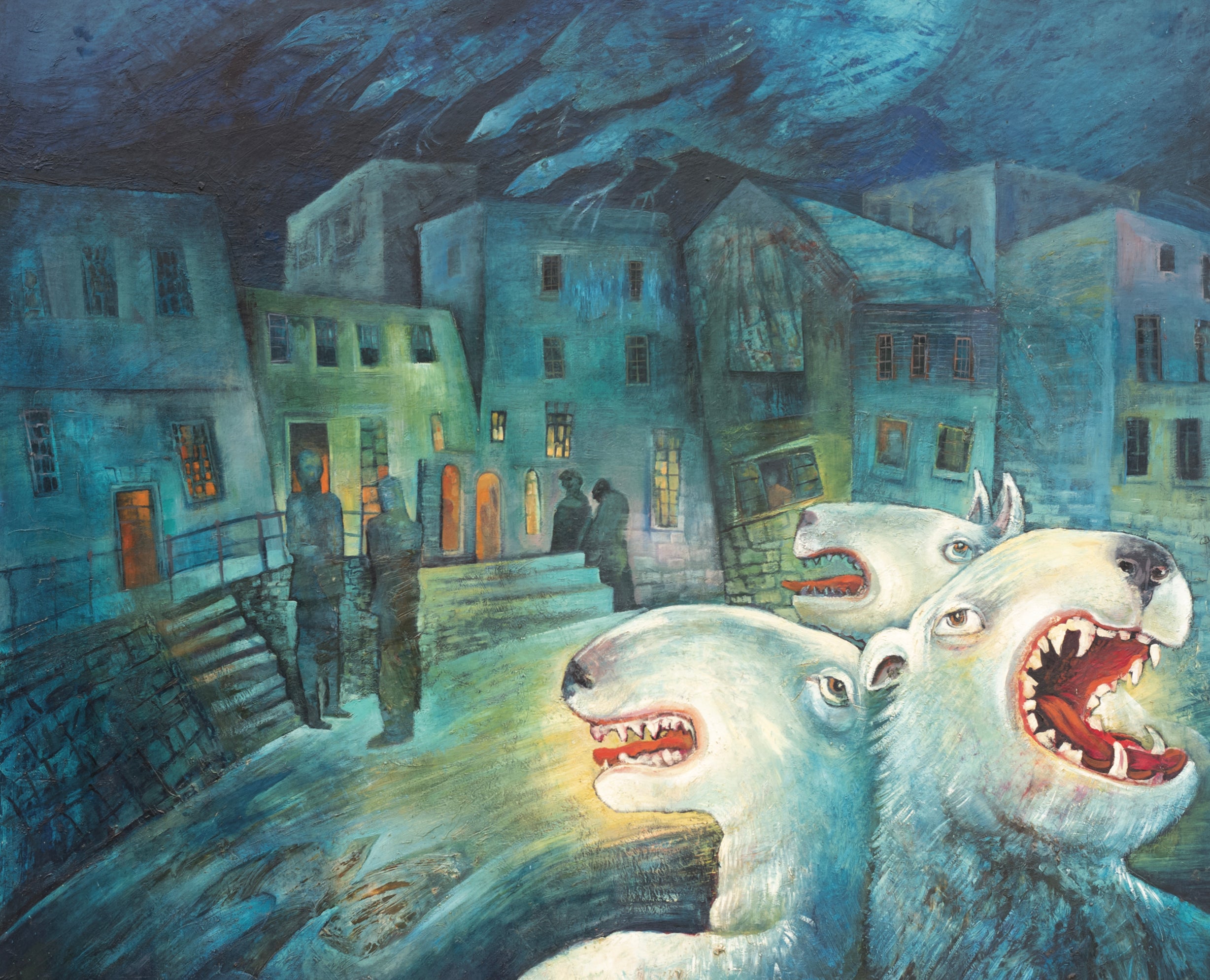

All his thought was of paint, and there were other artists who had been on his mind, among them Lucian Freud – ‘very slow, meticulous, and brilliantly so; but I’d rather overpaint a mistake and mix on the board, quick, spontaneous’ – and early Bratby, ‘when the colour was more limited, but specific.’ But Burra was the name that stuck out to me. In temperament and in background, they could not have differed more: Burra, the irascible, frail Sussex man born into great wealth, his privilege undercut by debilitating ill health; and Farrington, gentle, big and bear-like, whose hands seem made for the world of rough cultivation and untameable wilderness represented in his painting. Where they converge is as painters of suburban carnivalesque, portraitists of the down-and-outers of this world, and creators of a mythology of the ordinary and the forgotten. They are both underground painters; ‘in-the-ground’, perhaps, in Farrington’s case, so deeply has he inhabited the landscapes which he paints and the industries and working practices he depicts. Both painters proved a knack for merging metaphor with reality: for transforming, in paintings like City Dogs, streets at nightfall into underworld caverns, roads into Stygian rivers, a trio of rabid mongrels into a three-headed Cerberus, snarling at visitors of the dead.

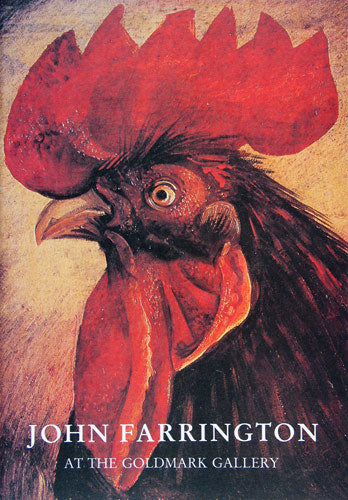

The Big Turkey II, oil on board, c1969

The Big Turkey II, oil on board, c1969

Both Burra and Farrington have given us a record of the places they grew up and have lived in, though neither painter worked en plein air, preferring instead to paint from memory or the occasional preparatory study. But unlike Burra, who frequently left his hometown of Rye in order to return to it afresh, and brought back with him experiences from abroad, be it Marseilles, Harlem, or Mexico, Farrington has never had the money to leave. If his paintings, even the most fabulous and allegorical, boast a gritty realism, it is because it is a realism he has lived himself. Look at Farrington’s mermaids, a far cry from the glistening temptresses of John William Waterhouse: salty wenches with seaweed in their hair, chomping down on strange, bipedal fish or beached in the harbour, their slick hoggish bodies wriggling among a fisherman’s catch. A Farrington sailor, beside a Waterhouse one, should certainly feel short-changed.

Farrington is a storyteller. That may not sound radical, but in the context of 20th century painting’s distaste for narrative and genre it makes his spiritual touchstone less those Neo-Romantics, exploring existential angst in the hills and valleys of England, and more the likes of Bosch and Bruegel. Farrington’s paintings – his stories – are folkloric. And like folk tales, they can be at once amusing and desperately cruel. Rarely are they easy: they detail nastiness, violence, malice and death as much as they embrace life, birth, tenderness and natural splendour. At their heart, like Bruegel’s, they are paintings of ritual, calendar, and season.

The Black Bull III, oil on board, 2001

The Black Bull III, oil on board, 2001

Throughout his life Farrington has kept, and watched the keeping and rearing of animals, and if anything could be said to be the ‘theme’ of Farrington’s life work, what his pictures are ultimately ‘about’, then it is this: the relationship between man and beast. Much of that relationship is cyclical, and his paintings depict those cycles in action through weather and season: the driving of sheep to shelter in winter and slaughter in spring. Many are concerned specifically with those cycles of life and death in the world of livestock: a great black bull herded by two armed men takes on the drama of Mithraic sacrifice; silver-blue fish, flopping breathless around boats on the blood-red pebbles, are mirrored by wheeling gulls overhead; a goatwoman steers her flock in fields littered with their ancestors’ skulls. And many see man trying, often with little success, to exert his control over the animal kingdom. Farrington as a young man bred cage birds and he still keeps rabbits (and, rather poetically, recently lost his cat on a caravanning expedition). He has worked as a cow- and pig-man, watched menacing boars held fast and castrated and tried, hopelessly, to stop a gluttonous sow from devouring her own litter – an altogether harrowing experience.

This capacity to blend the real and the imagined, the grounded and the magical, provides the special capacity in Farrington’s art to move. Like the ransacked boards on which his work is often painted, you need only begin to scratch the surface to find layers to the stories he is compelled to present. A series of whale paintings, for example, is woven with several autobiographical threads. Moby Dick was a favourite book of Farrington’s youth, and at 16, on leaving grammar school, he applied unsuccessfully for a position on a whaling craft in Liverpool. Years later, his brother was drowned in a scuba diving accident at Scapa Flow, swept deep into a current where he was forced to cut the rope connecting him to his diving partner. His body, Farrington tells me, was never seen again, though he spent 10 days on a fishing boat searching for him out at sea. The experience has informed so much of his painting, from the seascapes of desperate fish stock hoovered up by legions of fishing boats to the endless trail of a Melvillian white whale, harried by greedy sailors.

The Whale V, oil on canvas, 2001

The Whale V, oil on canvas, 2001

In Black Country middle-England where Farrington grew up, where, to borrow Burra’s phrase, you would find ‘not so much money about and absolutely not a bit of Fart’, the art schools of Dudley and Birmingham were a figurative beacon amid the smog-soot of collieries and industrial furnaces. At the School of Arts in Dudley, as a student in the late 1940s and early ‘50s, Farrington enjoyed the tutorship of two significant figures, the principal Joe Jago and Ivo Shaw. Between them they hoped to continue the legacy of William Morris in promoting and providing a broader crafts-based curriculum that could include book binding, typesetting, paper making and puppetry – virtually any attendant craft that might conceivably be turned to an employable trade.

The application of art – whether in design or illustration – they deemed critical, and critical to that was proper draughtsmanship. Farrington recalls he was made to keep a sketchbook, which his tutors routinely checked. ‘It taught us great discipline, because suddenly you were answerable for what you produced – or failed to produce.’

You hear few artists opine about the importance of self- discipline, but for Farrington, who for all his inclination to fantasy is steadfastly down-to-earth, it has been of great use. ‘Not knowing how to draw must be like writing with no full stops, with no punctuation,’ he tells me. Now in frailer health, Farrington has largely stopped painting in oils, but the drawings, often embellished with watercolour wash and waxy pastel resists, show precisely that eloquence that derives from rigour: a strength of composition, the balance of component elements, that underpins his more illustrative work. In the paintings, much of this facility is painted out, deliberately: you are left only with the colour, the wild setting, the intense movement of the piece. Like a piece of immersive prose or poetry, you don’t notice the punctuation: you forget that you are ‘reading’ at all.

Quarry Man III, oil on board, 2014

Quarry Man III, oil on board, 2014

If comparing pen drawings and pencil sketches to the paintings proves an illuminating experience, you can learn as much about Farrington’s work by turning the paintings to the wall. Early in his career, for want of cash and materials, Farrington took to painting on whatever scrap board and broken furniture he could find, and the habit never left him: bed boards, drywall panels – some still caked in patches of plaster – and shopfront fittings have all lent themselves to his work. Like icon painters working to the dimensions of a cabinet or an altarpiece, painting to these arbitrary dimensions has had a direct effect on Farrington’s pictorial organisation. Much of his work shares a pre-renaissance ‘busyness’, with concentrations of activity spread across the picture plane (as often cardboard as canvas). And as he so often paints without prior studies, save for those works produced in series, he has taught himself to respond automatically and adjust the architecture of the painting to a given board. Farrington’s work has a very clear sense of its frame: the movement of figures and brushstrokes often swirls to a central focal point, the sides of the composition warping round it like a fish-eye lens. You are drawn to the focus first, then rewarded with richness in the periphery.

‘He is painting, where many people

would be talking. He’s concerned

with visual communication, but it’s

literary communication really.’

Rigby Graham, 2012

Even in the earliest Social Realist paintings of his youth, Farrington’s ‘Black Country’ has never quite lived up to its name. The blast furnaces, factories, brickworks and steel mills of Dickens’ 19th century West Midlands, which famously ‘poured out their plague of smoke, obscured the light, and made foul the melancholy air,’ are rarely to be seen in their hellish entirety. Much of that industrial world he has locked behind garden walls, or left lurking forbiddingly on the horizons of rolling wastegrounds. Even his quarrymen, heaving steel carts of coal along tracks, find their red fires and oxide oranges doused by heavy rain and snow and dampened by Farrington’s favourite blues and greens.

You would have to turn not to Dickens but his contemporary and erstwhile colleague, Samuel Solomon, a writer from Birmingham whose ‘expertise’ ranged from railroads to husbandry, for an early description of the ‘Black Country’ to match Farrington’s own: ‘The majority of the natives of this Tartarian region are in full keeping with the scenery – savages, without the grace of savages, coarsely clad in filthy garments, with no change on weekends or Sundays, they converse in a language belarded with fearful and disgusting oaths, which can scarcely be recognised as the same as that of civilized England.’

Hunters, pen, ink and watercolour wash, 2017

Hunters, pen, ink and watercolour wash, 2017

Solomon was of course writing with tongue planted firmly in cheek – but that stereotyped ‘otherness’ that clings to the Black Country is by no means absent in Farrington’s paintings. Like these ‘Tartarian’ natives, like Burra’s hooligan farmers, Farrington’s locals often threaten descent to a wilder, bestial side. The longer they seem to spend with their dogs, their flocks, their herds, their caged fowl, the more they seem to mirror them: sprouting snouts and beaks, or dressed in animal costume, or with faces planted firmly in the trough gorging on pigswill.

While the industrial landscape has receded in Farrington’s work, it is the rural hills of South Shropshire that have taken their place as his primary setting: ‘A luvely, lownely position. It’s a lost world,’ he says of the valleys around Brown Clee Hill. The sour, round vowels in the local dialect that give it its distinctive melancholic lilt are in some way echoed in the paintings. His palette is vibrant, a natural palette ‘pumped up’, as the artist Rigby Graham described it, with an edge: greens curdling to white, oranges into twinging pinks. They remind me of Chagall – a comparison reinforced by both artist’s preference for filling back- and foreground space with animal forms: birds saturating the sky like Giottesque angels, waters choking with fish, sheep and pigs looming large as proud as the hills and mountains in the landscape around them.

Village Gardens, acrylic, 2021

Village Gardens, acrylic, 2021

For the greater part of my child- and young adulthood, a John Farrington painting hung outside my bedroom where I would pass it on a daily basis. Perhaps four or five feet in size along either edge, it was a portrait of a recurring character in Farrington’s work. Rumour had it she was the sister of the Anglo- Italian pianist Alberto Semprini. A birth defect had left her with severe rickets, her left leg clasped in a metal brace, and according to Farrington she would wander aimlessly about town in her pink dress, pushing an empty pram or pushchair for support. Occasionally Farrington has transposed her to a garden of Boschian delights, separated from a fire-lit cityscape behind her by a mystic sea full of leaping fish, but in our picture at home she was painted in situ, large and uncompromising: a great, lumpen, rose-coloured hulk, her painfully rounded frame dominating a suburban backyard, thick hands holding her pram with surprising delicateness, unfazed by the irate white bull terrier whose snout pokes through a hole in the broken blue fence behind her. Farrington, like Bruegel and Burra before him, has always been a chronicler of the unfortunate, the disaffected, the outcast. And in this portrait, he had given this strange, unknowable woman the serenity of a medieval saint.

I still don’t know what to think when I look at this painting. It is at once beautiful, unflinching, triumphant, and desperately sad. I take solace in the fact that Rigby Graham, Farrington’s friend and a far better reader of pictures than I am, found he had the same reaction: ‘It’s all a bit of a mystery and a mix-up at the same time,’ he said of Farrington’s work. ‘It’s that I find interesting. I just find it all funny. And I find Farrington both tragic in the one sense and funny in another. They’re the people that Farrington really painted for: the real children and the adults who are still children – of which I count myself one.’

City Dogs, oil on board, 1994

City Dogs, oil on board, 1994