Ceramic plate by John Piper

It’s a story of typical irreverence from Piper, who in fact held Picasso in deferentially high regard. Had he been alive to witness the Tate Liverpool’s recent attempts to equate the Fawley Bottom resident with the great Spaniard, Piper would no doubt have baulked at the premise – though the comparison reveals at least one interesting parallel to their lives: where Picasso has been embraced and celebrated for his diversity across media, Piper’s eclecticism has seen him overlooked.

Sketchbook page with Foliate head sketch; Piper's 'Green Man' foliate heads took inspiration from a variety of sources, from old English stone carvings to Picasso and even, as shown here, fashion photography in magazines

As Orde Levinson pointed out in the introduction to his catalogue of Piper’s graphic work, Piper’s own summation of Picasso’s frustrating virtuosity could as easily be applied to his own work: ‘[He] is a bad member of a school, either as pupil or master. His development cannot be seen as a progress, or as any kind of movement except a series of hops, skips and jumps all executed with great mastery. As a leader, therefore, he is unsatisfactory – exasperating.’

Piper's 'Four Seasons' foliate head etchings: (from top left to bottom right) Spring, Summer, Autumn, and Winter

That same ‘exasperating’ technical impulsion has seen critics baffled as to what to do with Piper. In an elegy to the neglected genius of Graham Sutherland, the writer William Boyd invoked an ancient proverb from Archilochus – ‘The fox knows many things; the hedgehog, one big thing’ – to compare the multi-talented Sutherland with the one-trick-portraitist Francis Bacon. Like Sutherland and most other ‘graphic’ British artists for whom printmaking constituted a worthwhile exercise, Piper was an inveterate fox, shifting stylistically from one medium to another; but the critics tend to favour a hedgehog: a Bacon, or a Freud.

In an attempt to make a hedgehog of Piper’s vulpine merits, most have reduced his art to two basic summarisations: that he was a topographer, with a particular interest in churches and stately homes; and that he was a Romantic.

'Nursery Frieze II': Piper's 'Nursery Friezes', both early works produced in 1936, reveal a confluence of stylistic sources including European avant-garde Cubism in Braque and Picasso and the provincialism of English artist-designers Edward Bawden and Eric Ravilious.

Both terms are used pejoratively. ‘Topography’ has all the dry associations of description and illustration without the expressive wilderness of landscape, while ‘Romantic’ is as much an insult by omission: romantic, they mean, as opposed to ‘avant-garde’, ‘modernist’, ‘contemporary’. Implied is a sense of backwardness: a parochial longing for the sentimentalism of Girtin, Cotman, Turner, and Constable.

Early Piper construction, from the mid-1930s

In fact, Piper’s engagement with early 20th century modernism was both profound and wide-ranging. In the early 1930s he produced Constructivist assemblages, dabbled in Surrealism, and made collaged abstractions in situ, bringing torn sections of paper with him to a scene and tearing and arranging in front of his subject (a method he would revive in the early 1960s, producing large-scale gouache collages of beaches along the North-West coast of France).

'Quiberon Bay', gouache with collage, 1962

Five further years dedicated solely to abstract painting taught him how to lay colours side by side, ‘when they have no goods to deliver except themselves’. This compulsive experimentalism was to become Piper’s defining characteristic as an artist, and would continue late into his career in collaborations with the renowned technicians Stanley Jones at the Curwen Press and Chris Prater at Kelpra Studios. ‘People think it dishonest to be chameleon-like in one’s artistic allegiances,’ he wrote in 1937. ‘On the other hand, I think it dishonest to be anything else.’ Some thirty years later, little – or rather, much – had changed: ‘I think this has been an age where particularly one has needed to change.’

'Abstract Composition', Piper's earliest lithograph, printed by Contemporary Lithographs Ltd.; the Cubist influence of Braque is clear to see

Though much of Piper’s superficial modernism was shed by the time he came to produce his great architectural suites of the 1960s and ‘70s, these later prints owe much to that formal training. ‘I think the discipline of Cubism and the styles which followed have been a great help to me’, he wrote in 1964, the same year A Retrospect of Churches was published: ‘They made me realise the absolute need, however romantic or sentimental one wanted to be, for extreme discipline in painting.’

'Oxburgh Hall, Norfolk', 1977

Scrutiny of the early Cubist experiments of Picasso and Braque, coupled with an almost encyclopaedic knowledge of Gothic and Victorian architecture, provided him with an acute sense of the impact of the vertical line pitted against the horizontal. In a great many of his church portraits the former is emphasised, exaggerated even, in both the main subject and the periphery: the church tower at Castlemartin looms up into the rainclouds like an obelisk, its skyward movement echoed by tendrilled trees that appear to stretch up toward the downward streaks of black rain.

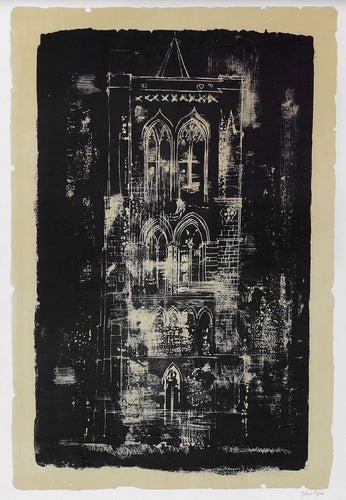

'Castlemartin', 1976

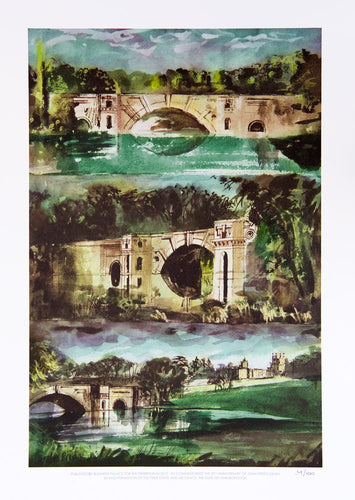

In other prints, buttresses, turrets, transepts and tracery windows all contribute to this vertiginous leaning, as do the wild, chalky grasses and mass of gravestones, like fingers pushing up heavenward through the dirt. Elsewhere, in the sprawling estates of Ettington Park, or the broad forecourts of Blenheim Palace and Waddesdon Manor, Piper stresses the horizontal in vigorous bands of colour.

'Blenheim Palace', 1988

Piper often employed this Classical mechanism, encouraging the eye symbolically up towards the firmament or out across more remote vistas; but this formalism was always borrowed to serve, rather than supress, the subjective experience: ‘Romantic painting is about the particular,’ he wrote, ‘not the general. The subjective artist who does not particularise and define makes no progress but loses himself in a miasma.’

'Wymondham, Norfolk', 1981

Underlying the topographical prints is a profound Romantic spirit: a sense of the particular, melancholy and nostalgia, the genius loci – spirit of place – that suffuses Piper’s work. Myfanwy described it as the ‘mysterious magic presence that collects the dreams of the past which, like wasp stings, accumulating in the blood, accumulate in the mind and imagination.’

A trio of etchings from Piper's 'Scotney Castle, Kent' suite, 1982

Here that accumulation muddies on the page: weather, place, time, and environment seem all to bleed and coax into one, from the jewelled patches of colour that spill from brickwork to earth to the ubiquitous, Stygian washes of dark blue, green and black that so often mist Piper’s views.

'Two Suffolk Towers', 1973

Piper did not do colour by halves. There is little by way of delicate, pastel hues in his palette: the blues are ultramarine, Prussian, royal; the reds sanguine and scarlet, bottle, emerald, and feverish greens, amber, turquoise, liquorice and cruor amid cigarette-ash grey.

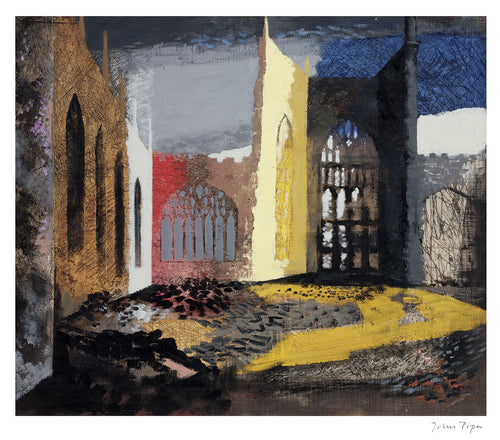

'Wigmore Abbey Gateway', 1981

But of all colours, it was black that ultimately dominated Piper’s work, that defined almost every print in his oeuvre. In his earliest wood engravings – pastoral vignettes in the Neo-Romantic manner of Sutherland and Nash – he realised the monotone vigour in the reverse colouration of white line on black block. In the later works, black is near omnipresent: black ink, black charcoal, thick black washes.

'Reclining Nude (Myfanwy)', charcoal and watercolour, 1972

Piper recognised black as the colour of arrest: the pen ink that captures a pose in a sketchbook, the dark charcoal of a life study, the black wash that grounds colour, gives it limits, cages it and confines it to the page, the black that captures the experienced moment.

'Castleblythe', 1983

'Castleblythe', 1983

Piper discussed colour at length with his technicians, especially in silkscreen preparations with Chris Prater, and he well knew the chromatic power of black to lend punch to neighbouring shades; how it killed the light penetrating the paper, forcing it to illuminate areas of lighter colour, like the lead frames of stained glass.

'Buckden Palace, Cambridgeshire', 1982

Piper’s black squalls were to become something of a joke among his detractors: presented with the portentous wartime skies of Piper’s Windsor Castle watercolours, King George VI famously remarked, ‘You seem to have had very bad luck with your weather, Mr Piper.’ But in a number of topographical prints, the preponderance of black seems less a comment on England’s inclement weather and more a signal towards the other obsession of Piper’s life: the camera.

'Christchurch Spitalfields', 1964

A trio of clerical portraits in Piper’s Retrospect – Fotheringhay, Christ Church in Spitalfields, and Gedney’s tower in the fens – have the white-on-black quality of photographic overexposure; Harlaxton blue, ethereal and ghost-like, appears like a processed negative.

'Harlaxton (Blue)', 1977

The camera was to play a central role in Piper’s post-war career, both literally in the incorporation of photographic materials, but also in Piper’s changing perspective. Works like the theatrical panels produced for Benjamin Britten’s Death in Venice opera feel almost directed, as if composed through a viewfinder.

Three of Piper's 'Death in Venice' panels, 1973

This new perspective was made explicit in the title of the Eye and Camera prints. Every image is potentially filmographic: from the murder mystery body shapes that seem to reference the title sequences of Saul Bass, to the voyeuristic shots of Myfanwy in knee-length boots, with all their intimations of deviant kink.

'Eye and Camera: Blue to Yellow', 1967

Stones and Bones, perhaps Piper’s strangest graphic offering, took the photographic theme further: photographs blend into chalk lines and acid washes, as if peeling, melting and bubbling from chemical heat.

Its videographic end papers, one in negative, the other positive, bookend a bizarre narrative combination of images, from annotated landscapes and rock formations to photographs of primitive stone carvings and brutally chopped up pornographic snaps.

'Stones and Bones XXIII', 1978

Collectively they have the psychological thrill of late Hitchcock, a montage of disparate images that deal with conflicting, contemporary themes: sex and death; the direct, drawn image and the detached, mechanical photograph; the intimate and the panoramic; the human figure and the landscape of form.

'Eye and Camera', from the eightieth anniversary portfolio, 1983

If the Eye and Camera and Stones and Bones series revealed Piper as an unsung modernist, in his topographical prints he was happy to admit a certain provincialism. The titles of his places, especially the churches, are often peculiarly English: there is a satisfaction in the particularity of local parish or hamlet.

Significantly, Piper was a practising Christian, and so he brought to these places a concern that was not just aesthetic, but spiritual. The flannel-grey brick of the parish in Ottery St Mary and the ruins of the Benedictine abbey at Binham are lit up with the burning orange of Pentecostal fire; their wild, unexpected bursts of colour suggest moments that transcend mere appreciation.

'Ottery St Mary', 1987

Piper’s unearthing of the roots of forlorn and forgotten churches echoes something of the spiritual quest of T.S. Eliot in Little Gidding, where ‘the communication / Of the dead is tongued with fire’ and the ‘intersection of the timeless moment / Is England and nowhere.’ Piper’s churches seem to provoke an existential question of the kind that so dogged Eliot in middle-age: is Christ really to be found here, too, in country parish and priory, so very far from the holy land?

'Ruined Church, Bawsey', 1982

Levinson described Piper’s sense of place as ‘a sort of spiritus mundi, the soul of the world, with memory passed on from generation to generation – that line of foam at the shallow edge of a vast, luminous sea made ‘ready’ for us to recreate, to explore, enjoy and appreciate.’

'Ruined Chapel, Isle of Mull', 1975

That idea of ‘generation to generation’, the historical tradition which so fascinated Eliot, lies at the crux of Piper’s work, be it topographical, figurative, technical or experimental. In the swaggering views of stately homes, or the resurrectional portraits of crumbling, moss-covered ruins, the presence of prior souls, spiritual simultaneity through the ages, presses against the page in those great swathes of black and brilliant colour that could only be Piper’s own. His was a very individual talent.