In 1968, with tensions sharply rising in the Vietnam War, the sculptor and printmaker Leonard Baskin was tasked with commemorating a much older conflict: the doomed charge of General Custer against Sioux and Cheyenne tribes at the Battle of Little Bighorn. The results were among his strongest drawings to date – and seeded a fascination that would last over 30 years.

As the clocks struck midnight on 4th July, 1876, fireworks shot overhead at Independence Hall in Philadelphia, where gathered the great and the good of American society to celebrate the country’s 100th birthday. While rocket bursts illuminated the crowds below, hundreds of miles away telegraph operators hastily relayed a message that would soon put an end to the festivities: General George Armstrong Custer, dreamboy commander of the 7th Cavalry and hero of the frontier, lay naked and dead with all 200 and more of the men under his command, slain by a coalition of Native Indian tribes on the elevated grasslands of Little Bighorn River.

Edgar S. Paxson, Custer’s Last Stand, oil on canvas (detail), 1899

To understand the curious hold the legend of Custer had on the American popular imagination, you have only to look at the immediate outpouring of reproductions of the event that followed it. By the late 1960s, Mitchell Wilder, director of the Amon Carter Museum in Fort Worth, Texas, described counting close to a thousand different versions of the battle in their picture archives, making ‘this sad occasion…the most memorialized single event in American history.’ From beer bottle caps, cigarette cards and bumper stickers to preposterously grand oil paintings, almost every one of them focused on the imagined ‘realities’ of the battle itself: an amassed fray of Indians and Blue Coats, smoking pistols and carbines, and heaps of dead bodies, the panoramic vista of the Montana horizon glimpsed beyond. Here is the familiar blueprint of the great Hollywood western epic: the theatre of man’s brutal territorial disputations, dwarfed by a vast landscape otherwise unspoilt by human contact. But the Custer episode has proved special – an event so tightly wrapped up with the great American foundation myth, and the guilt complex at its heart, that popular culture would always find it relevant and meaningful. It comes as no surprise to learn that when the US Army presence in Vietnam hit an all-time high – and public support for the war an all-time low – gritty exploitation films (Soldier Blue, 1970; Ulzana’s Raid, 1972) and picaresque revisionary histories (Little Big Man, 1970) looked to the frontier, and to Custer especially, for their allegory of choice: troopers sent to die in an unjustified war, in unfamiliar terrain, against a more experienced guerilla enemy.

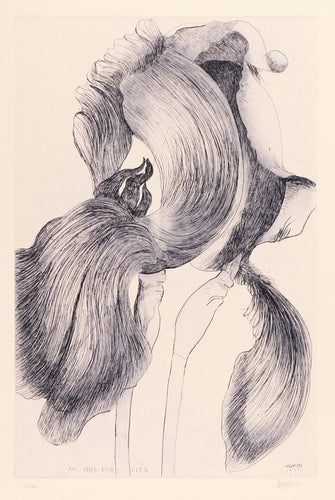

In all this noise, the Native American voice was often lost. It was not an Indian artist, but the New Jersey-born and Brooklyn-raised sculptor Leonard Baskin whom Vincent Gleason, publications director of the National Park Service, approached in 1968 to illustrate a new souvenir handbook detailing the events – and the fallout – of the battle at Little Bighorn. Though not native, Baskin’s insistence on the importance of figurative art in an era concerned with abstraction made him an ideal candidate, and his talents were prodigious. At 15 he had apprenticed to the sculptor Maurice Glickman before discovering William Blake at Yale. Blake’s influence struck him, he remembered, ‘like a run-away locomotive. The impact was staggering, irresistible and over-whelming.’ He took up etching and woodcuts and, while still a student, established the now-famous Gehenna Press. Named after the valley southwest of Jerusalem, synonymous with hellfire and purgation, it seemed an appropriate imprint for an artist whose work had inherited the dark and angular psychology long evident in Germanic art, from Grünewald and Altdorfer through to Paula Modersohn Becker and Kathe Kollwitz.

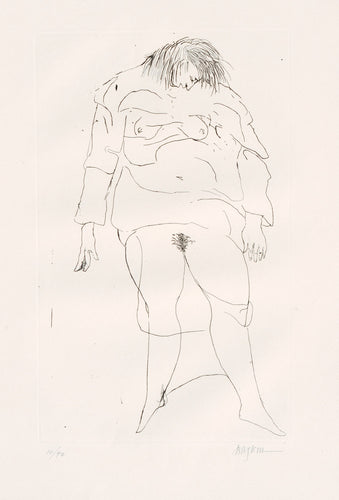

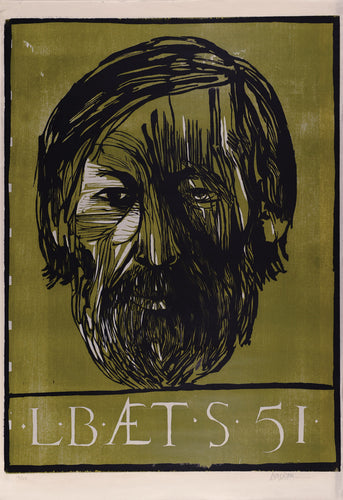

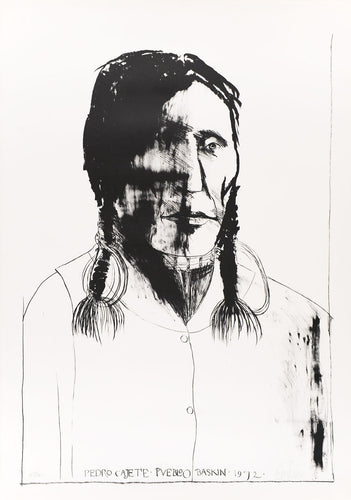

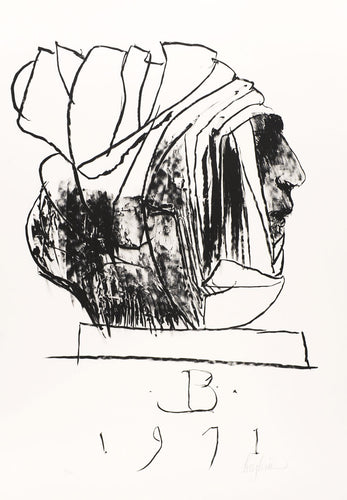

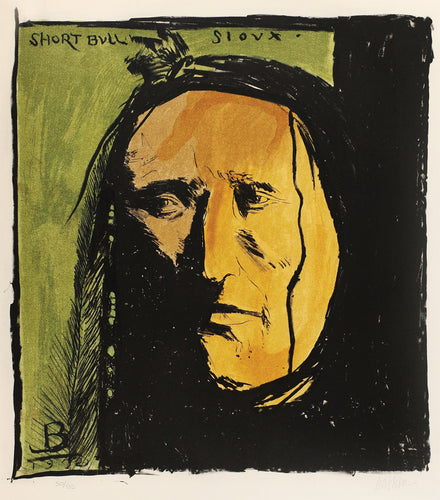

But what drew him to this unusual project was precisely that sense of historical continuity, a desire to make the past actors of the Bighorn as present as possible. To an audience of fellow printmakers at the American Institute of Graphic Arts a few years before, he had reaffirmed his dedication to the human condition as the ultimate subject, and the human figure as its eternal vehicle: ‘I have an exhilarating and oppressive vision of man as immutable, intact and practically unalterable. I could have walked with Socrates, hauled stones for Chartres, set type for Bodoni, and had my skull cracked by a cossack’s club in any of innumerable pogroms. I am joined to that colossal continuum of man thrusting through the centuries.’ Baskin knew little of the Plains Indians’ history when he accepted the commission. He found in Custer a simultaneously fascinating and repugnant protagonist, awed by ‘his sense of posturing, his sense of dressing up, his incredible mania about himself.’ But he soon realised that what he had been asked to address was not, as the battle was commonly known, Custer’s Last Stand, but that of the Natives who defeated him. With their success at Little Bighorn, the Sioux and Cheyenne coalition had won the battle but lost the war. Retribution from the white man was swift and terrible, ensuring the end of the old ways in the Black Hills and beyond. What began as a series of portraits of the main players in the Bighorn affair – Custer, Sitting Bull, leader of the defiant Sioux, and their colleagues – sparked an interest in other forgotten Native leaders. Baskin continued to produce drawings and lithographic portraits into the ‘70s and beyond: prints, watercolours, and hand-bound books, right into the last decade of his life.

National Parks Custer Battlefield Poster, 1968, with illustration by Leonard Baskin

The son of a rabbi and brother of two more, Baskin was not the first Jew to become interested in the plight of the American Indian. A full 50 years before the battle of Little Bighorn itself, the former diplomat Mordecai Manuel Noah – half Ashkenazi, half Portuguese Sephardic, and a prominent public figure in New York – sought to establish a utopian Zion on Grand Island in the Niagara River. Natives were invited to create a new society with his fellow Jewish citizens: Noah was one of many who subscribed to the eccentric theory that Native Americans were descendants of one of the ten Lost Tribes of Israel. A vague and otherwise superficial ‘otherness’ shared between Native and Jewish immigrant faces later established the Hollywood tradition of Jewish actors taking Native roles over actual Indians, as gloriously parodied by Mel Brooks’ Yiddish-speaking chief in the cult classic Blazing Saddles (1974). But Baskin made no mention of his own Jewish roots having informed his approach to Little Bighorn. A curious irony had brought their stories together: each a people without a spiritual home, one indigenous, the other permanently immigrant. Both had, within living memory, faced cultural extinction. The subtext was there for all to see. ‘It would be fitful and absurd for me to recount the slaughter, with disease, booze and guns,’ Baskin declared of his illustrations; ‘but allow me, (in raging haplessness), to indict our government and all of its peoples, not merely for the broken treaties and conventicles, but for allowing Indians to be shut up in reserves, live in penurious degradation, in blight and misery and left to the deadly mercy of the Bureau of Indian Affairs.’

This was a story going back hundreds of years, of course, to the arrival of the first European colonists in the Americas; but the beginning of the end of Native life on the Great Plains could be said to have lain at the Battle of the Little Bighorn.

Like so many stories from the frontier, its catalyst was gold, rumoured to be buried in the Black Hills that were sacred to the Sioux Nation (and other Indians), an alliance of Lakota and Dakota tribes. Settlers had been making deeper incursions into Sioux territory, their railroads penetrating westward with attachments of troops to protect surveyors. The Sioux had themselves been ‘invaders’ of these lands, pushed westward from Minnesota by their own enemies and then by cessions of land to the United States. Migrating to the Great Plains, they subdued the Cheyenne and displaced smaller tribes like the Crows. By the mid-19th century, accords between the tribes and the US government attempted to halt the steady flow of settlers, but most were made without any intention of enforcing them. But after suffering humiliating defeats at the hands of the Lakota leader Red Cloud, in 1868 US officials drew up the Fort Laramie treaty. On offer was an invitation to establish the Great Sioux reservation: the Black Hills and the surrounding lands would be their exclusive home, with rights to hunt without fear of repression, and federal aid through the winter, ending dependence on the buffalo which were already fast disappearing at the hands of European pelt traders. In exchange, the Sioux would give up vast swathes of their territory – lands formerly promised by older treaties – to accommodate the growing numbers of settlers. Many took up the offer, but several thousand, under the leadership of the charismatic Hunkpapa chief Sitting Bull, refused – among them the fierce Oglala warrior Crazy Horse, an expert raider responsible for many of the US army’s worst defeats at the hands of the Natives. They remained adamantly tied to the old ways of Plains life, refusing any negotiation with the white man.

On the opposing side was George Custer. Blond, vivacious, bold – many said to a fault – Custer owed his short but stratospheric career to the Civil War (he lay dead a major general at 25). He quickly climbed the ranks through acts of reckless daring, courted admiration and criticism from his peers, and even made an enemy of President Grant. Like Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse, he had his own experiences of US raiding parties against the Cheyenne near Yellowstone while laying track for the North Pacific Railway.

In 1974 Custer and his infamous 7th Cavalry company were commissioned to explore the Black Hills – land that now lay deep inside the bounds of the Sioux reservation, with the Little Big Horn tributary just beyond. His governing generals wanted to establish a fort nearby, to keep watch on the reservation Indians; but more importantly, local prospectors suspected that untapped seams of gold would be found within the hazy blue peaks. When Custer’s expedition returned, they confirmed the rumours were true. A gold rush ensued; attempts to purchase the territory from the Natives were fruitless, thanks to the defiance of Sitting Bull and his own agitators. An air of inevitable catastrophe hung over the Black Hills.

There were striking similarities between the two opposed parties: internal conflicts, rivalries between chiefs and officers alike. The US Army had been quick to exploit the existing tensions between the Sioux and the tribes they had ousted from the Black Hills, recruiting scouts from the Crow, Blackfeet and Pawnee who were only too happy to see their old enemies forced from their lands. Baskin was fascinated especially by the conflicted psychology of these men caught in the middle, their allegiances branded in the Indian naming tradition: the life and striking, painted face of White Man Runs Him, he later wrote, became a personal obsession.

But in the days and weeks before the Little Bighorn battle, Indians from various agencies were spotted converging together, forming a far larger band than any of Custer’s superiors had expected, united in grievance at the ongoing desecration of the sacred lands in the hills. What began as a game of cat and mouse, with troopers stalking the travelling camp, soon escalated as the Indian coalition moved along the Yellowstone river. US generals feared the camp would disperse, and that they would miss their one opportunity to deal a killing blow to Sitting Bull’s resistance. On the evening of 24th June, Custer’s Crow scouts brought news that the camp trail was headed west toward the Little Bighorn. This, he surmised was their only chance, a gambit worth taking, though support was too far behind him to catch up. Custer was forced – or blindly elected, depending on your interpretation of events; the jury is still out – to charge on an enemy that far outnumbered him. The battle was over before it had even begun.

Leonard Baskin, Chief Wets It, 1972, lithograph, signed edition of 160

After Custer’s devastating defeat, the wrath of US government rained down upon the Sioux and the Cheyenne. Indians were disarmed at gunpoint as they returned to reservation agencies, including those who had taken no part in the conflict. The Black Hills were forcibly sold. Troops made attacks on tipi villages, driving any Natives who still refused to be penned in reservations into ever more precarious circumstances. Sitting Bull fled to Canada, but within a year Crazy Horse had no choice but to surrender his entourage at the Red Cloud Agency in Nebraska. A few months later and he was dead, murdered by a camp guard while purportedly resisting arrest.

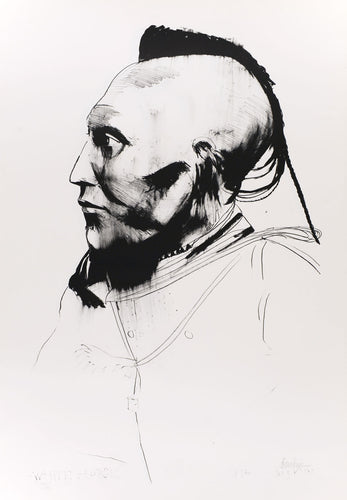

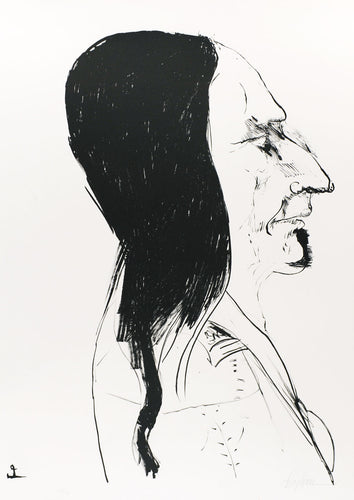

It would be another four years until Sitting Bull threw down his own weapons at Fort Buford in July 1881, the last man of his tribe to surrender. He too was killed in custody while Indian agency police attempted to arrest him, fearing a potential Lakota rebellion. In almost every photographic portrait of him, Sitting Bull faces us head on, his face proud but weathered; Baskin’s side profile falls somewhere between Piero della Francesca’s Duke and Duchess of Urbino and a police mugshot. Days later, a detachment of the 7th Cavalry (now under new management) were tasked with disarming the remaining Lakota at the agency when a gunfight turned into a massacre. As many as 300 Lakota men, women and children lay dead at the temporary camp at Wounded Knee Creek, their bodies left to freeze in the December snows.

The subjugation of Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse, representing the freedom of pre-colonial Plains life, served only to reinforce the idea of ‘Manifest Destiny’ prevalent among the settlers: the puritanical belief that God’s designs for America had fated their expansion in the West, ever since the first Europeans had arrived. Native tribes were an obstacle to civilised progress; their destiny, by contrast, belonged to a doomed and ‘primitive’ past. The message now was clearer than ever: assimilate, or face extinction. Frank A. Rinehart and Edward S. Curtis were among the more prominent photographers who attempted to document the passing of this way of life, and Baskin drew heavily, often literally, from their work. Rinehart’s otherwise sympathetic portrait series of representatives from the 1898 Indian Congress in Omaha, Nebraska, contrasted the regalia of warrior headdresses against painted backgrounds and vignettes of modern living, as if to accentuate that the Indians belonged to a race confined to a bygone era. Edward Curtis, on the other hand, took a more direct approach. With a generous sponsorship from the financier J.P. Morgan, he took equipment with him as he travelled the country, living alongside the tribes he met and photographed, declaring that with his series of portraits ‘I want to make them live forever.’ (Among his given names were ‘Shadow Catcher’, in reference to his camera, and ‘The Man Who Sleeps on His Breath’, after the inflatable mattress on which he slept).

As beautifully captured as they are, Curtis’ portraits are not perfect: he was guilty of ‘dressing up’ Natives in clothing they had long since abandoned, and of staging ritual performances. But they intended to preserve a dignity and reflect a stoicism that seemed fundamental to Indian survival into the early 20th century.

In 1969, as Baskin’s illustrations were being put through the press, Vine Deloria Jr., a member of the Standing Rock Sioux, published the short manifesto Custer Died for Your Sins (the title soon caught on as a rallying cry for the American Indian movement). More than simply a call for more federal aid or political representation, in his book Deloria made the point that for too long Native Americans had existed in a monolithic state of black and white: cast as villains and heroes, noble savages tied up with a Romanticised vision of the untouched American frontier. What he yearned for was a richer understanding of the Indian identity: one that placed front and centre their sense of civic belonging, their often wryly surreal sense of humour, born of a diverse spirituality.

Leonard Baskin could find little humour in the events he was asked to portray, the people he depicted. But there are no heroic horse-back portraits, no contemporising backdrops, no egregious centring of stock Native American paraphernalia – feathered headdresses, tomahawks and peace pipes – in his portraits. Instead, Mitchell Wilder writes, Baskin brings these historical figures to us – with all their cautions, their mistrust, their beauty and their melancholy – as he could, ‘[cutting] through a century of mediocre, apocryphal pictures to reveal the actors of this tragic drama as they were, not in the event, but in life and in death.’