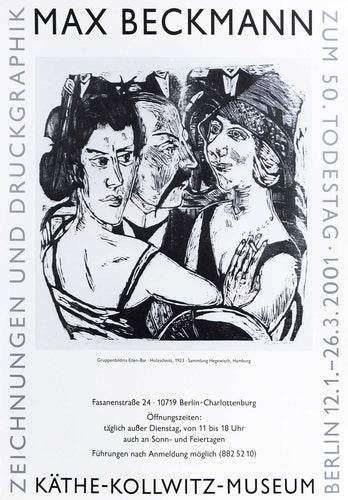

Inspired by a recent Max Beckmann poster to come through the gallery front door, we decided to return to this article on Beckmann's emphatic Gesichter suite of drypoint etchings originally published in November 2014.

Beckmann's prints revealed an enormous change in the artist's own style as he moved towards the violent energy typical of the German Expressionists. His depictions of the impact of WWI on both troops and civilians left behind at home make for intensely powerful images.

'so momentous an event as that Great War?' - a poignant mock battle commences in 'Playing Children'

'so momentous an event as that Great War?' - a poignant mock battle commences in 'Playing Children'

With the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, the collective German conscience was faced with seismic change. Never before had nations had to contemplate such routine and industrial slaughter as took place in those four years; never had societies been burdened so heavily, not just with the physical realities of such killing - and what visceral realities they were - but also with sustained emotional and mental realities. How should - how, even, could - society consider and react to so momentous an event as that Great War?

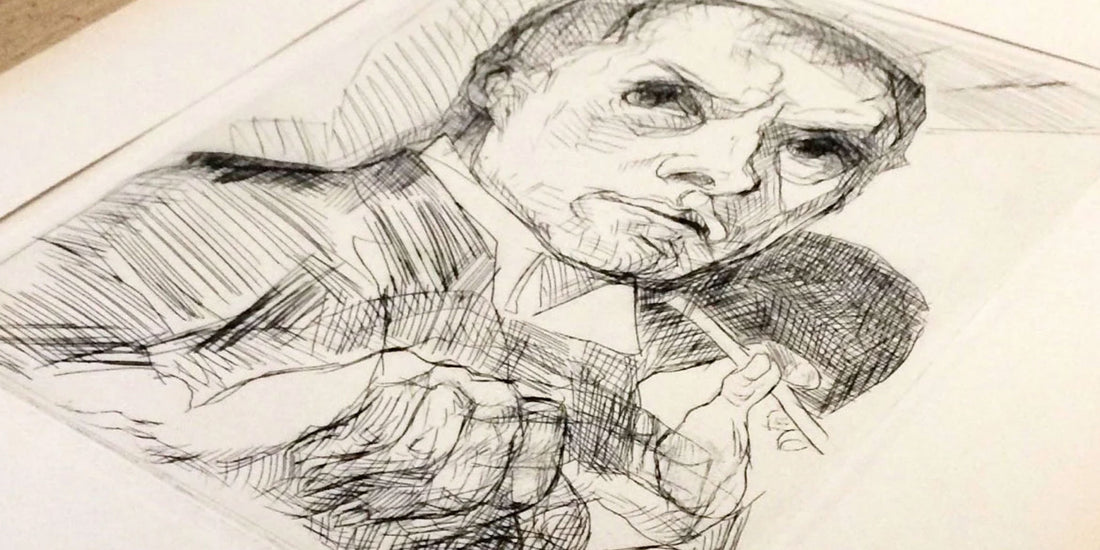

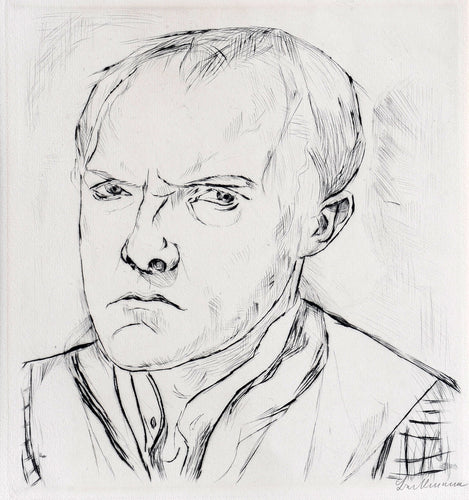

'There is nothing I hate more than sentimentality' - elf portrait in drypoint (1918)

'There is nothing I hate more than sentimentality' - elf portrait in drypoint (1918)

This was the question with which a young Max Beckmann concerned himself. Born in 1884, Beckmann had by the mid-1900s begun to nurture an artistic career at a time of great change in the world of art. Impressionism had met its peak, and emerging was a band of raw and revolutionary artists - expressionists, fauvists, artists of so-called ‘new painting’. Critics of his early work grouped him with the revolution: his paintings were ‘visionary’ and ‘modern’, and he has since been termed a German Expressionist, though this was a label from which Beckmann continually and vocally fought to distance himself.

'raw and revolutionary' - Beckmann's vigorous line at work in 'The Yawners' (1918)

'raw and revolutionary' - Beckmann's vigorous line at work in 'The Yawners' (1918)

These pre-war years, as he noted in his Creative Credo of 1918, were a time of ‘business interests’, a ‘mania for success and influence’. Allocated work as a medical orderly when war broke out, however, Beckmann was suddenly faced with the hideousness of blood-soaked operating theatres and truncated victims, whose dispersed limbs had been left on the mud-lands of the front. Looking ‘straight into the stupid face of horror’, he could not help but reassess his place in this new world: it is unsurprising that the wartime period saw as immense a transformation in Beckmann’s style and approach as is evidenced in the Gesichter suite, arguably the most emphatic of Beckmann’s life and career.

'hideous operating theatres and truncated victims' - 'The Large Operation' (c.1914)

'hideous operating theatres and truncated victims' - 'The Large Operation' (c.1914)

Produced between his first experiences of war in late 1914 and the ceasefire of 1918, each image in Gesichter cannot be divorced from the influence of the ongoing conflict; nevertheless, Beckmann’s perspective in this period is varied and subtle, often approaching wartime themes from the quiet unease of urban and domestic life behind the battle lines. In images like ‘The Yawners’ or ‘Café Music’, Beckmann depicts scenes that are ostensibly mundane, everyday, seemingly unencumbered with the kinds of visceral and emotional brutality we see so prominently in prints like ‘Madhouse’ or ‘The Large Operation’; but his claustrophobic reduction of space, the energy of his drypoint incisions and the alternately expressionist and cubist, jagged and rasped, thickly bitten lines contribute to an underlying unrest that perfectly encapsulates how the terrors of war trickled through to the consciousness of civil society.

'claustrophobic reduction of space and thickly bitten lines' - 'Theatre' (1916)

'claustrophobic reduction of space and thickly bitten lines' - 'Theatre' (1916)

In the aftermath of the conflict, Beckmann’s printing work began to attract the attention of critics, one such - the art historian, collector and publisher Julius Meier-Graefe - offering to produce a portfolio for Beckmann in 1919. The years that followed Germany’s defeat saw intensely concentrated graphic production amongst artists: reparations were harsh, and the economic turmoil the war had left in its wake meant that the print, which could be produced cheaply and in great numbers, was far more viable than a reliance on canvases alone.

In Beckmann, however, the change of focus to the graphic medium had coincided with fundamental changes in stylistic approach. Printing served not just an economic purpose, but (more importantly) an artistic developmental purpose too. It was a clarity of vision and depiction that Beckmann sought; drypoint, in which the line is everything (lines in which Hofmaier, the authority on Beckmann’s prints, suggests he achieved ‘an incredible purity…which often astounds’), became the artist’s graphic tour de force.

'an incredible purity...which often astounds' - 'Evening' (1916)

'an incredible purity...which often astounds' - 'Evening' (1916)

Meier-Graefe selected nineteen of the best images from Beckmann’s wartime output to be produced in a standard edition of 60 and a deluxe of 40. The title Gesichter - translated literally as ‘faces’, but also ‘visions’ or ‘appearances’ - was suggested to Beckmann, incorporating the various characters bored, brutalised, deranged and disillusioned that he had portrayed and which constituted his image of a now post-war German society.

'Gesichter': literally 'faces', but also 'visions' or 'appearances' - 'Family Scene' (1918)

'Gesichter': literally 'faces', but also 'visions' or 'appearances' - 'Family Scene' (1918)

In his Creative Credo, written not long before Gesichter’s publication, Beckmann writes passionately of his artistic principles:

There is nothing I hate more than sentimentality. The stronger my determination grows to grasp the unutterable things of this world, the deeper and more powerful the emotion burning inside me about our existence, the tighter I keep my mouth shut and the harder I try to capture the terrible, thrilling monster of life’s vitality and to confine it, to beat it down and to strangle it with crystal-clear, razor-sharp lines and planes.

Today, some one-hundred years beyond the start of the Great War, and at a time when so much of our remembrance is recounted through the narrative of British poets, artists and writers, Beckmann’s Gesichter offers us an alternative perspective, in parts equally profound and poignant, and of undeniable artistic significance and value.