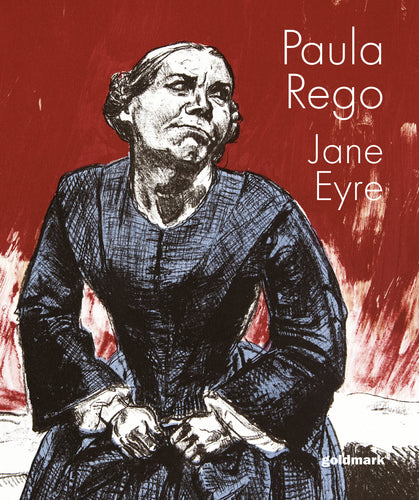

‘I always need a story. Without a story I can’t get going,’ Paula Rego told an interviewer on the eve of her 70-year retrospective at Tate Britain in 2021. ‘I’m always looking for new stories.’

Paula Rego photographed at Curwen Studio

As an artist who started drawing at the age of four, the first stories that fired Rego’s imagination were her native Portuguese folk tales, often involving cruelty which, like all children, she confessed to finding ’fascinating’. As is the way with folk tales, the cruelty was often directed at women.

Rego’s stories have always had female heroines: ‘I make women the protagonists because I am one,’ was her simple explanation. Brought up in a liberal household under the dictatorship of António de Oliveira Salazar, which preached that a woman’s place was in the home, she gravitated towards heroines who defied societal expectations. In the early 2000s she found a new story with just such a heroine: Jane Eyre.

Detail from Up the Tree, signed lithograph from Jane Eyre by Paula Rego

Invited by master printmaker Stanley Jones to try lithography – a medium relatively new to her – at his legendary Curwen Studio, Rego embarked in 2002 on what would become a series of 25 lithographic prints inspired by Brontë’s iconic novel. Sometimes working directly on the stones in Jones’s Cambridgeshire studio, sometimes drawing on transfer paper in her own studio in London, she experimented with a range of techniques as innovative as her approaches to the text.

She came at Brontë’s masterpiece from an oblique angle. Her first acquaintance with its characters was through Wide Sargasso Sea, the prequel to Brontë’s story written by Jean Rhys more than a century later from the perspective of Bertha, the fragile Creole beauty married by the young Rochester for her money, who ended up as the ‘madwoman in the attic’. Inevitably, Rhys’s book coloured her vision. In an interview following the publication of six of her images as stamps by the Royal Mail in 2005, the 150th anniversary of Brontë’s death, Rego described Bertha and Jane as ‘two sides to the same woman’, but with different fates. Unlike the reserved but quietly manipulative Jane, Bertha acts out her frustrations and suffers the consequences. Brontë and her narrator weren’t kind to Bertha. There’s a racist undertone to Jane’s description of the shadowy figure who invades her bedroom on the eve of her planned wedding to Rochester: Rego’s Jane is afraid of her own shadow.

When the stamps came out, Brontë fans were taken aback by Rego’s unorthodox vision. As an artist rather than an illustrator she made free with her sources, treating them as launchpads for pictorial flights of fancy. ‘It all comes out of my head,’ she said. ‘All little girls improvise, and it’s not just illustration: I make it my own’. One newspaper journalist complained that the Jane of the stamps was ‘middle-aged and almost mannish’. While the Jane of the novel is no beauty – readers are repeatedly told she is plain and small – she possesses an elfin charm that bewitches Rochester. Rego’s Jane, however, is a strong-looking woman with a lived-in face at odds with Brontë’s petite ingenue. If she looks familiar to connoisseurs of the artists’ work it’s because she was modelled on the faithful Lila, the Portuguese carer-turned-model who came to nurse Rego’s husband Victor Willing through the final stages of multiple sclerosis in the late 1980s and went on to pose for her women ever after. In this series, she plays both Jane and Bertha.

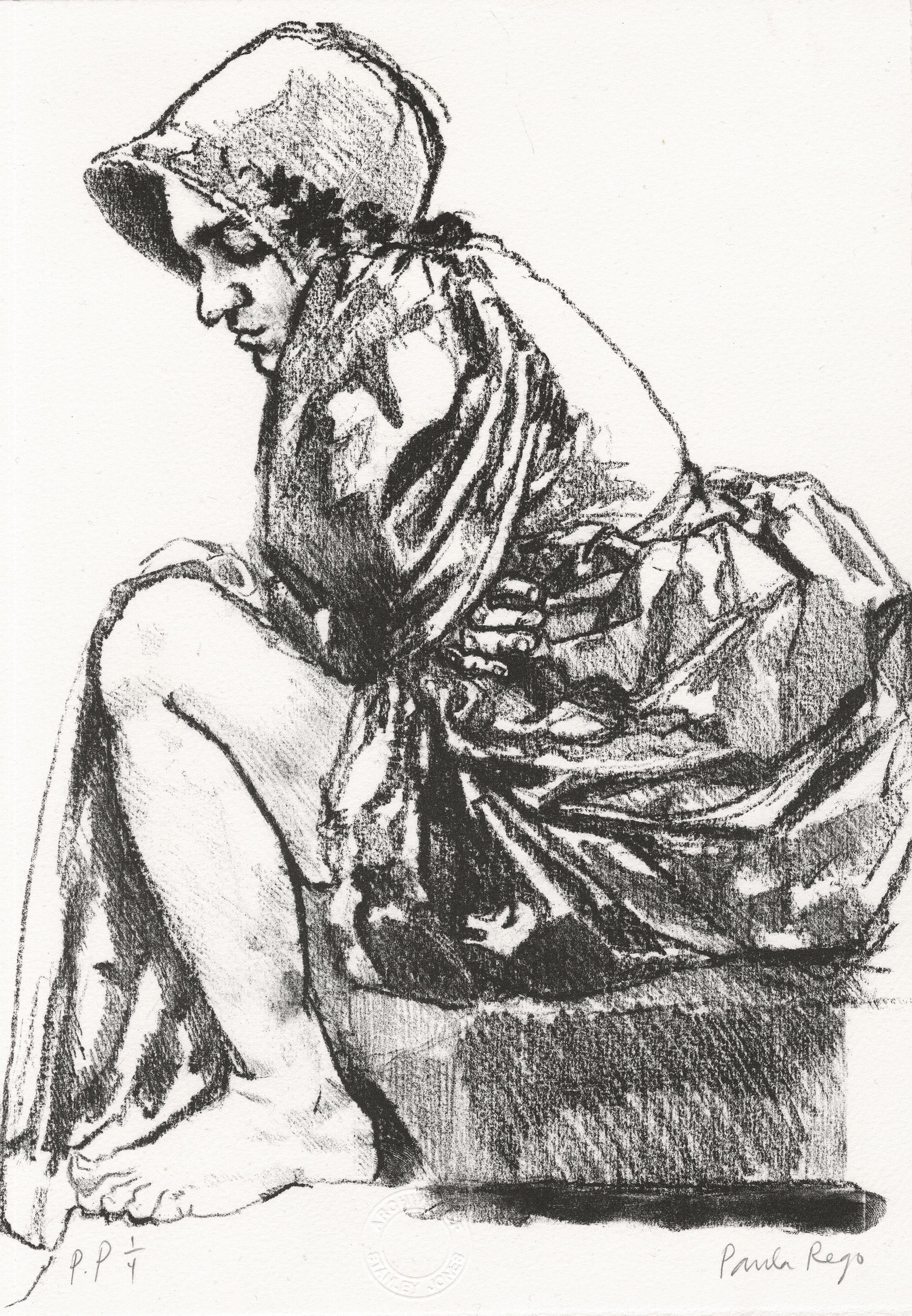

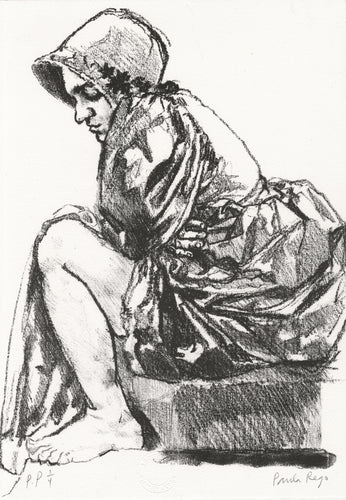

Jane, signed lithograph from Jane Eyre by Paula Rego

The scenes of Jane’s early life – with one notable exception, which I’ll come to later – stick closest to the text. From her childhood years as the unloved orphan at Gateshead we have Girl Reading at a Window, picturing Jane hiding behind a curtain from the bully John Reed, who is lifting the book with which he is about to strike her. The institutional horror of her school years at Lowood is covered in more detail. In The Refectory, tiny new girl Jane is dwarfed by enormous fellow pupils three times her size; in The Schoolroom, a crowded composition reminiscent of Max Klinger’s The Plague, Klinger’s hospital beds are replaced by desks and his crucifix-wielding nun by the cruel Miss Scratcherd taking a cane to the gentle Helen Burns’s neck. In The Inspection Jane is herself the victim, a doll-like midget on a stool ‘exposed to general view on a pedestal of infamy’ by a giant Mr Brocklehurst whose lugubrious face is half the length of her body. The only moment of tenderness shows Jane and Helen nestled in bed on the night of Helen’s death from consumption in a pose recalling Toulouse Lautrec’s brothel scenes of female companionship. Rego’s sources are as broad as her imagination.

Detail from Girl Reading at a Window, signed lithograph from Jane Eyre by Paula Rego

Rego’s stock characters are the resilient, resourceful woman and the seemingly dominant male she gets around: the big man in the jackboots unmanned by the little woman in the pinafore. Jane and Rochester were perfect for the parts. On arrival at Thornfield, we’re introduced to a mounted Mr Rochester in the moment before he falls from his horse. Wearing jackboots – a favourite symbol of male authority for Rego – he looks the epitome of the dominant male, as authoritative as an equestrian statue. Rego glosses over his tumble on the icy path and Jane’s coming to the rescue, a premonition of the blinded Rochester’s later dependency. We’re given no inkling of whose foot the boot will end up on, although the story carries curious echoes of the shifting power dynamic in Rego’s own marriage following her husband’s sickness. Rochester’s features bear a resemblance to Victor Willing’s and the house in the background is not a Gothic battlemented mansion but the Portuguese house in Estoril in which Rego grew up.

Mr Rochester, signed lithograph from Jane Eyre by Paula Rego

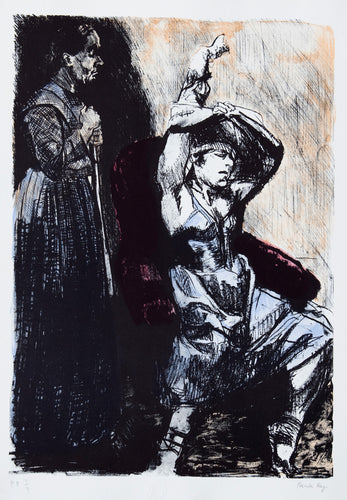

At Thornfield the master of the house lords it over his womenfolk. In Adèle Dancing, his little French ward pirouettes for him in the frock he has brought her from Paris, displaying all the coquetry of her opera dancer mother, his former mistress, whose shadowy ghost dances in the background. In Pleasing Mr Rochester, even the dogs compete for the master’s attention, while Adèle primps and prances and Jane pulls up a chair for her employer to sit in. But Rego’s Rochester is not as straight as he seems. In Dressing up as Bluebeard, she puts her own spin on the charades scene in which a turbaned Rochester disguises himself as ‘the very model of an eastern Emir’. Perhaps surprisingly, she omits the scene in which he cross-dresses as an old gypsy fortune teller, preferring to preserve his masculinity as a false idol to be knocked off its pedestal. In The Scarecrow, Jane and Bertha collaborate in dressing a lay figure in a field full of swooping pigeons: ‘Rochester is just a dummy,’ was Rego’s explanation of this curious scene.

Detail from The Scarecrow, signed lithograph from Jane Eyre by Paula Rego

From Bluebeard to The Wizard of Oz, echoes of fairy tales resonate through Rego’s imagery. Cinderella comes to mind in Getting Ready for the Ball, showing Thornfield’s female house guests dressing for the evening. As described in the book, the glamour of this occasion floods Jane’s formerly grey world with colour and the central image of this 2m triptych is the most colourful in the series. In Brontë’s telling, Jane is dazzled by ‘the impression of high-born elegance’ as the women emerge from their rooms and descend the stairs ‘as a bright mist rolls down a hill’, but Rego turns them into ugly sisters. She projects Cinderella through the lens of Velázquez, with a dwarf borrowed from Las Meninas joining the ugly sisters clustered around the dressing table and the background mirror and doorways evoking Velázquez’s complex composition. Jane appears twice on the left, as a grown-up Cinderella figure in the shadows and as a child leaning against the back of the dressing table drawing – a self-portrait of the artist as a young girl.

Getting Ready for the Ball, signed lithograph from Jane Eyre by Paula Rego

For much of Brontë’s story Jane appears a peripheral figure, an observer and narrator rather than an active participant, and Rego depicts her as a passive victim in Crumpled – following her fit at Gateshead after being locked in the red-room – and in Crying, after her assault by John Reid. But the determined set of her head in the back view Jane Eyre suggests a fortitude already visible in Inspection. There is nothing in Brontë’s novel to connect with the mysterious image, Up the Tree, which Rego explained as ‘Jane trying to escape’, though the crossbar-shaped branches are more suggestive of a crucifixion. There is a religious overtone, too, to Night, showing Jane making her getaway from Thornfield under cover of darkness, her cloaked figure silhouetted against a starry sky like the Virgin Mary’s in Velázquez’s Immaculate Conception – escaping unsullied, virginity intact.

Detail from Night, signed lithograph from Jane Eyre by Paula Rego

In Come to Me, she takes control of her destiny. ’It was my time to assume ascendancy,’ Jane says in the novel and in Rego’s print she grabs it in both clenched fists. This marks the pivotal moment in the story when its heroine is saved from emotional death as a dutiful, unloved wife of the missionary St John Rivers by the telepathic voice of Rochester crying out ‘in pain and woe, wildly, eerily, urgently’. In the novel it’s not Rochester who says: ‘Come to me’; it is Jane who passionately responds to his voice: ‘I am coming! Wait for me! Oh, I will come!’ This is the moment when Jane abandons her sexual inhibitions. For all she knows she is giving herself to a married man, though the fiery red of the sky behind her in Rego’s print tells us otherwise.

Come to Me, signed lithograph from Jane Eyre by Paula Rego

In a novel whose dramatic tension builds towards the climax of the discovery of the mad woman in the attic, it could be argued that Bertha, not Jane, is the central character. Rego gives her equal billing in her prints. Like Jean Rhys, she refuses to show her as the grotesque figure described by Jane on her nocturnal visit to her bedroom but as a slim-waisted, graceful woman, a sort of Creole Scarlett O’Hara. In the most violent image in the series, Biting, Bertha is not the wild beast imagined in the book but the apparent victim of abuse by her brother, who far from the tame, vacant-looking Mr Mason described in the novel is a smiling torturer with a face like Frankenstein’s monster and a hand on one of her breasts. With her petticoat slipping, it could be a rape scene from a graphic novel.

Biting, signed lithograph from Jane Eyre by Paula Rego

If Jane personifies the sterile prospect of spinsterhood, Bertha embodies the worst that can happen in a marriage. In The Keeper, her phlegmatic minder Grace Poole supports her tragic figure as in a living Pietà before which a kneeling Jane appears to be worshipping. Rego imagined an element of jealousy on Jane’s part prompted by the suspicion that Rochester was still visiting his wife by night: an open doorway in the background of Getting Ready for the Ball gives us a peep show glimpse of one such visit. Her Rochester remains under the sexual spell of his exotic first wife, a more pungent enchantment than Jane’s elfin influence. Bertha is the wicked fairy to Jane’s good one.

Detail from Loving Bewick, signed lithograph from Jane Eyre by Paula Rego

Reading stories, said Rego, ‘liberates other bits of your mind and what gets out often has nothing to do with the story’. One of the most commonly reproduced prints in her Jane Eyre series seems to have the least to do with Brontë’s story. In Loving Bewick, Jane‘s description of rare moments of happiness at Gateshead immersed in Bewick’s History of British Birds are reimagined by Rego as Jane being fed like a nestling by a giant pelican. What would Charlotte Brontë have thought? As a talented amateur watercolourist, her heroine was herself capable of wild imaginings: on the wall behind Pleasing Mr Rochester Rego pictures one of Jane’s paintings of a shipwrecked man drowning while a cormorant flies off with his bracelet. Just as Brontë’s story liberated bits of Rego’s mind, so Rego’s imagery might have inspired Brontë to new flights of fancy. One suspects they would have got on like a house on fire.

Laura Gascoigne, April 2023

Laura Gascoigne is a freelance critic and regular reviewer for The Spectator