Music played a vital part in the life of Ceri Richards – painter, printmaker and himself a gifted pianist. While Debussy soothed the artist’s spirit and provided his own source of inspiration, it was the spectre of Beethoven that fascinated Richards, and to whom he paid homage with a powerful suite of screenprints late in his own career.

Portrait of Beethoven by Ceri Richards, screenprint, 1970

Ludwig van Beethoven was, in Ceri Richards’ eyes, the archetypal Promethean talent, struck down for his creative genius. In 1970, at the end of his own life, he paid homage to the composer’s legacy with a powerful series of prints.

An older lady recently approached me at my desk to inform me that ‘We’ve just seen you on the television.’ Months ago I foolishly agreed to front short films for the Goldmark Gallery and remarks like these from well-meaning customers are now an occupational hazard. ‘My husband couldn’t stop talking about your hands.’

Thin and wrinkled beyond their years, I’ve long been conscious of these hands; a ‘palm reader’s nightmare’, as friends would sometimes joke. They’re commented on frequently enough that I now have a stock response. ‘Yes, they’re pianist’s fingers’ I replied. This is only half-true, for I am a lapsed musician, my amateurism to shame by a sister who is a professional violinist and a brother who is a jazz pianist. But it is a life of playing music, more than anything, that has brought home to me the dynamic expressiveness of the human hand, in all its peculiar intricacy. Hands, I recently learned, are not just the nightmare of the palmist but of AI image generators too, the results often smeared and distorted. For all their ability to read and conceive facial expressions, the more mysterious articulation of the hand remains beyond machine learning powers (for now, at least).

Portrait of Ceri Richards by Ida Kar, 1960

It was the hands in this photograph of Ceri Richards, taken by Ida Kar in 1960, that first drew me to it, and its similarity to the portrait of Beethoven Richards drew ten years later, taking as his model a portrait by August von Klöber made in 1818: the way the fingers curled pensively around the paintbrush and stylus, Richards’ left hand cradling his right, Beethoven’s clutching his manuscript. The authorial hand as an imaginative symbol or motif was to become increasingly important in Richards’ work, particularly toward the end of his life. They had been a key element in his erotic work: long, roving fingers, caressing and probing like tendrils or unfurling like the petals of a flower. Ever preoccupied with the transformative power shared of art and the natural world, he was also aware of the hand as the primary human contact point in creation: of the translation of work and feeling through his fingers to his medium, and, unsettled in later years by illness, of the hands that were writing his legacy and the work they would leave behind.

Pastorale, 1970, screenprint by Ceri Richards

Music had been a constant in the life they were writing. His father directed the local chapel choir in Dyfnant, near Swansea, and Richards played the piano from a young age. In his art music weaves its way through flowerings of themes, blooming in periods of obsession with a particular musical work or image, as was the case with Debussy’s Cathédrale Engloutie, the ‘sunken cathedral’, based on the Breton legend of a mythic cathedral submerged off the coast of the island of Ys. In the vast series of canvases that followed, ‘music,’ as the critic Norbert Lynton put it, ‘so often a guest in Richards’ paintings, becomes the subject itself...’

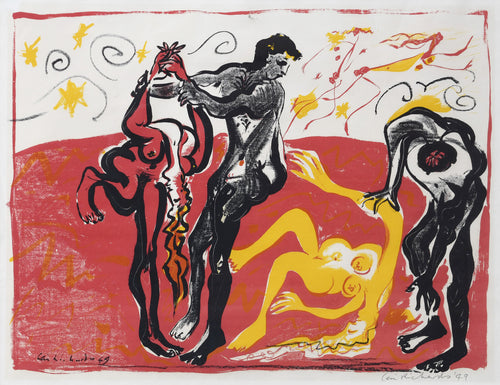

It was not until the early 1950s that the music and the spectre of Beethoven became ‘subject, not guest’ of his paintings, and that the previously anonymous female pianists he began painting in the 1940s, sometimes reminiscent of his wife and fellow artist, Frances, were first identified as St Cecilia, patron saint of music. In Pastorale, one of ten screenprints dedicated in homage to Beethoven and published some twenty years later, Richards reproduces one such painting: Beethoven and St Cecilia I (1953). Above it lies a panoramic view of Vienna from the Belvedere Palace by Bernardo Bellotto, and above that, music soars over the city, emanating from a pair of disembodied, baton-wielding hands and given abstract form in the spattered bars of blue and white that are themselves a quotation from one of Richards’ Cathédrale paintings.

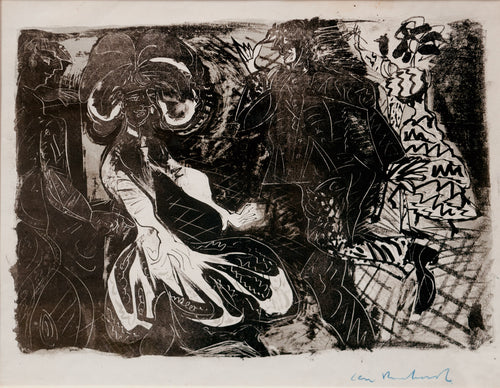

Bagatelle, 1970, screenprint by Ceri Richards

His title references Beethoven’s ‘Pastoral’ symphony, a great paean to the sustaining peace of the countryside. But the ambiguity of Richards’ St Cecilia, head furrowed in contemplation and shrouded in silent blackness, reveals that all is not as it seems. At the time of the 6th symphony’s premiere in December 1808, Napoleon’s forces were gathering to march on Vienna, intent on occupying the city for the second time in four years. Once an admirer of the French leader, the violent imperial ambitions of the Napoleonic wars would utterly disillusion Beethoven. He wrote later that he preferred the ‘empire of the mind’; but those ethereal hands, casting their spell over Vienna, would become important to Beethoven’s legacy too, when total deafness confined him to the thoughts in his head. His only means of communication then were his hand-written notes and the extraordinarily moving compositions of his final years.

Major - Minor Orange and Blue, 1970, screenprint by Ceri Richards

The idea for a series of prints celebrating the bicentenary of Beethoven’s birth came from Richards’ dealer. 1970, coincidentally, was to be the last full year of Richards’ life – a period plagued with doubts, medical complications, and a foreboding sense that his own end might be near. To undertake an homage to Beethoven entailed both a moment of self-reflection and the challenge of manifesting a lifelong fascination. He had bought and read countless books on the composer’s life and his music, including the volumes of letters and notebook correspondences Beethoven had left behind, unable to converse in speech. His fixation on the composer as the archetypal tragic Romantic artist who, to borrow Dylan Thomas’ exhortation, would ‘rage, rage against the dying light’ was almost eclipsing. ‘When I look into the mirror,’ Richards said, ‘Beethoven looks back at me.’

Violon d'Ingres, 1970, screenprint by Ceri Richards

Through the medium of screenprint he could collate this lifelong relationship, picking and choosing visual artifacts from Beethoven’s life and his own art to explore his strong identification with the composer: not one of ego or genius, but emotional intensity. The series presents – to use the musical cliché – variations on a theme. Music and composer are made combined subjects, inseparable from one another; photographic relics, almost like devotionals, join hand-drawn elements to unite historical reference and Richards’ own personal expression. In a Matisse-like interior, reminiscent of much earlier paintings, Music Room features the ghostly image of the composer’s death mask. Violon d’Ingres is titled after the French phrase, which refers to a second hobby or talent: the artist Ingres famously loved to play the violin (as did Matisse, and Richards the piano). Richards reproduces Ingres’ drawing of the virtuoso Paganini, with whom he performed, while the pale white silhouette of a violin recalls Man Ray’s very different work of the same name: a nude photograph of the model Alice Prin, better known as Kiki de Montparnasse, with two f-holes sensuously superimposed upon her back.

Music Room, 1970, screenprint by Ceri Richards

Unlike the Cathédrale theme, where the intangible impression of the music find concrete expression in architecture and the subterranean textures of sunken stone, Richards had no immediate visual equivalent for the vastness of Beethoven’s sound. In Major-Minor, Orange and Blue, he approximates two sound waves, their initial shapes borrowed from the enclosing bars of musical notation, warm orange and cool blue straightforwardly suggesting major and minor keys. Embossed lines in the print surface suggest the three-dimensionality of sound, while a raised, pitch-black ear at its centre (flanked by portrait and manuscript) becomes a tragic symbol of sound’s absence. Like the apple or the flower in his nature paintings, Richards makes full use of this new significant symbol. In Missa Solemnis, named after Beethoven’s magisterial mass, the ear returns again as an icon unknotting, twisting and transforming into a treble clef. But the most powerful image in the series is perhaps also its strangest. The Inaudible Tenth recalls Beethoven’s unfinished 10th symphony, which exists today only in fragmentary notes. The composer himself has been fragmented and disarticulated, reduced to a solitary ear and an aural canal in the shape of a mouth. Besides the fields of bright, flat colour elsewhere in the suite, this print is poignantly stark and empty. A bouquet of flowers and manuscript hangs in the air, while behind it a tube of paint spills a skyburst of blue across the page and a punitive thunderbolt, hurled from the hand of Zeus, crashes from above.

The Inaudible Tenth, 1970, screenprint by Ceri Richards

Art was, for Richards, the translation of complex associations, its input the fullness of human experience: not just light, colour and texture, but scents, sounds, memory too. ‘[It] must create a sensation inseparable from the feeling I have for the subject from which it stems,’ he once wrote. ‘A subject is a necessity, for it presents a renewal of problems and discipline…Discovering a subject for a start – which for me means one that haunts me...’ And as this last symbol of The Inaudible Tenth portends – a lightning crack blasting the deafened ear unable to hear it, no eyes illuminated by it – the plight of Prometheus was the subject Richards discovered within the Beethoven series, and which he would continue to explore after its completion. Prometheus completes the suite’s wide-ranging symbols and associations: as Richards recognised himself in Beethoven, he recognised both artist and composer in this allegorical figure of myth, who for centuries stood for the arts, for science, and the spirit of all human creative innovation. The fate of Prometheus answered Richards’ lasting preoccupation with life, death and cyclical regeneration, which he shared with his compatriots Dylan Thomas and Vernon Watkins. The myth encompasses not just the better known episode illustrated in the two prints Prometheus I and II, but a whole series of circular conflicts. Ultimately, it is a tale of theft and betrayal. Prometheus aids Zeus in the downfall of his own people, the titans, only to defy his new ruler and steal the gift of fire for mankind; and Zeus’ punishment ravages the very titan who had helped secure his victory, condemning him to an eternal cycle of torture, chained to a mountain column with an eagle sent daily to pluck out his regenerating liver.

Prometheus II, 1970, screenprint by Ceri Richards

The Prometheus myth is exceptional in Richards’ work in that the regeneration it describes is purgatorial, a hellish and miserable existence punctuated only by intense suffering and made possible only by Prometheus’ blessed immortality. In some later versions of the myth, Prometheus yearns for the eagle’s arrival, grateful for his excruciating company that punctuates the numbing eternity of countless years of isolation. In another retelling, the pain of the eagle’s raking beak is so great that Prometheus grinds his back into the rock he was bound to in order to escape its reach, becoming one with the mountain. What symbolism does Ceri Richards intend in his identification between Beethoven and Prometheus? That to create, represented by the gift of Prometheus’ flame, is to condemn oneself to an endless series of painful deaths and regenerations, each one exposing the seat of the soul.

Prometheus I, 1970, screenprint by Ceri Richards

Tellingly, the figure of Prometheus who appears in the Beethoven suite – and whom Richards has made to resemble the composer, as he did Beethoven himself – meets salvation in the form of Heracles, who slays the eagle with an arrow loosed from his bow. In Prometheus I (pg. 2) the action is condensed, the myth stripped to its basic elements, but in Prometheus II (right) the episode footnotes a series of panels with Beethoven in front of the piano, resembling a speechless cartoon strip. Here the imagery of the myth and of the frustrations of the creative process – a series of deaths before the keyboard, and the salvation of completion – are merged into one: the ropes binding Beethoven-Prometheus are like the staves of a musical manuscript.

When I asked my siblings if they could condense Beethoven’s legacy to a single sentence, my sister came back with a phrase from her musician partner: ‘The personal, or the human, is offered a gateway to the ecstatic.’ As Richards saw it, his life was the apotheosis of ‘not going gentle into that good night’, the last years of his life bringing greater richness and complexity to his music: looking back to the church music of the Baroque while hurling Classicism into the Romantic era. And in this late suite, Beethoven’s gift of enlightenment and the theft of his hearing come to represent the ultimate theme of Richards’ own life: the supernatural, the natural, and the human in simultaneous coexistence.