Of the old etchers, Rembrandt, as all acknowledge, is the sovereign prince. - P. G. Hamerton (1866), art scholar and author of Etchers and Etchings

Born in Leiden in 1606, Rembrandt was to become the most important artist of the Dutch Golden Age, celebrated by Gombrich in The Story of Art as one of the greatest painters who ever lived. But it is also Rembrandt’s unparalleled skills and achievements as an etcher that have made him a continuous source of inspiration to scholars and collectors alike, as well as a profound influence on many later artists including Goya, Whistler, and Picasso.

'The Casting Out of the Money Lenders'

'The Casting Out of the Money Lenders'

The son of a successful miller, in his youth Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn was a disappointment to his father. Wealthy enough, despite his lower class trade, to send his son to the local Grammar School, he had high hopes for the young Rembrandt's academic future when, at the tender age of 14, he enrolled at the Leiden University. An agricultural man, he wanted and expected better things of his son: a career in the courts, perhaps, or a professorship in Latin rhetoric at some flourishing school or university.

(above) 'The Tribute Money'; (below) 'The Circumcision in the Stable'

(above) 'The Tribute Money'; (below) 'The Circumcision in the Stable'

Instead, Rembrandt left the University after a few months and became an apprentice painter. Had there been the early telltale signs of genius, the indication that here was the Netherlands next great master, the blow to his father's dreams might well have been softened. But the life of a young, up-and-coming artist had been made more difficult in the aftermath of the Protestant Reformation.

The Catholic Church had frequently employed local artists for commissions and offered patronage to individual painters, but with the Protestant criticism of the lavish wealth spent on their iconography, painters and sculptors had to look to independent clients and private patrons for their financial support. Initially apprenticing with a local painter in Leiden and establishing a joint workshop there, in 1631 Rembrandt travelled to Amsterdam, swapping the uninspiring streets of his birthplace for the hustle and bustle of the Dutch port city.

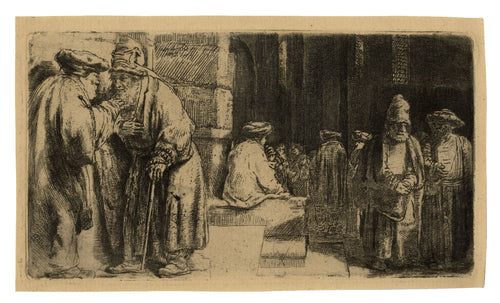

'Jews in the Synagogue'

'Jews in the Synagogue'

17th century Amsterdam was a hugely wealthy city, a hotbed of commercial trade which saw merchants across Europe converge on its busy docks. For an artist just beginning to make a reputation for himself it offered endless inspiration, and Rembrandt was enthralled. He drew everything he saw, from out-of-pocket traders arguing over stock to beggars and waifs in alleyways, absorbing the sights around him and revelling in spectrum of human life gathered in the city streets.

Lodging with a local art dealer, Rembrandt also met his first wife here - Saskia, the cousin of his well-to-do landlord. Wedded in 1934, their marriage - by all accounts a happy one - was plagued by the illness of their many young children, only one of whom (Titus) would survive infancy. Saskia became something of a muse to her husband, who etched her into his self-portraits and surreptitiously inserted her figure and face into his history paintings, as he frequently did himself.

'Self-Portrait, with Saskia'

'Self-Portrait, with Saskia'

By the late 1630s, Rembrandt had made a name for himself as a portraitist and painter of historical scenes, courting commissions from some of the wealthiest families in the city. As well as painting oils and sketching in the streets, he had begun to experiment with the process of etching, a method of printmaking that had until now mostly been used to reproduce famous canvases by Italian masters for distribution amongst artists, dealers and patrons.

He quickly became a master of the medium, making technical innovations within the etching, burin and drypoint processes that would shape the way modern etching is done even to this day. To the artist, this new method of depiction was as important as his many portraits, and he invested great time and energy into building up a portfolio of printed work that would see his name and genius known throughout Europe and further abroad.

(above) a self-portrait in a darkened room, demonstrating Rembrandt's supreme mastery of light and shade in the etching medium; (below) portrait of 'Lieven van Coppenol'

(above) a self-portrait in a darkened room, demonstrating Rembrandt's supreme mastery of light and shade in the etching medium; (below) portrait of 'Lieven van Coppenol'

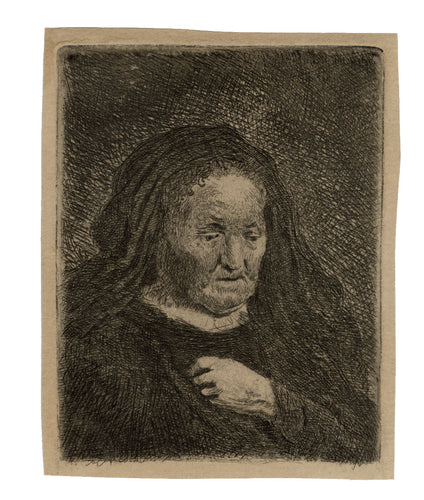

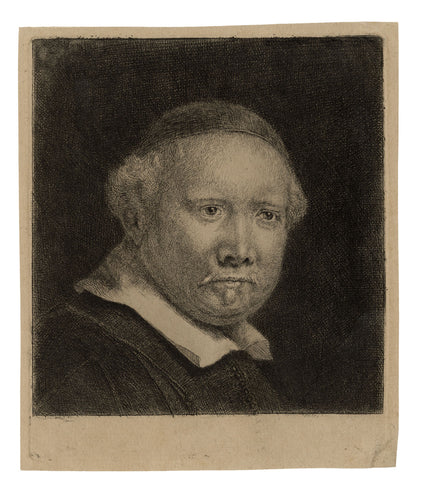

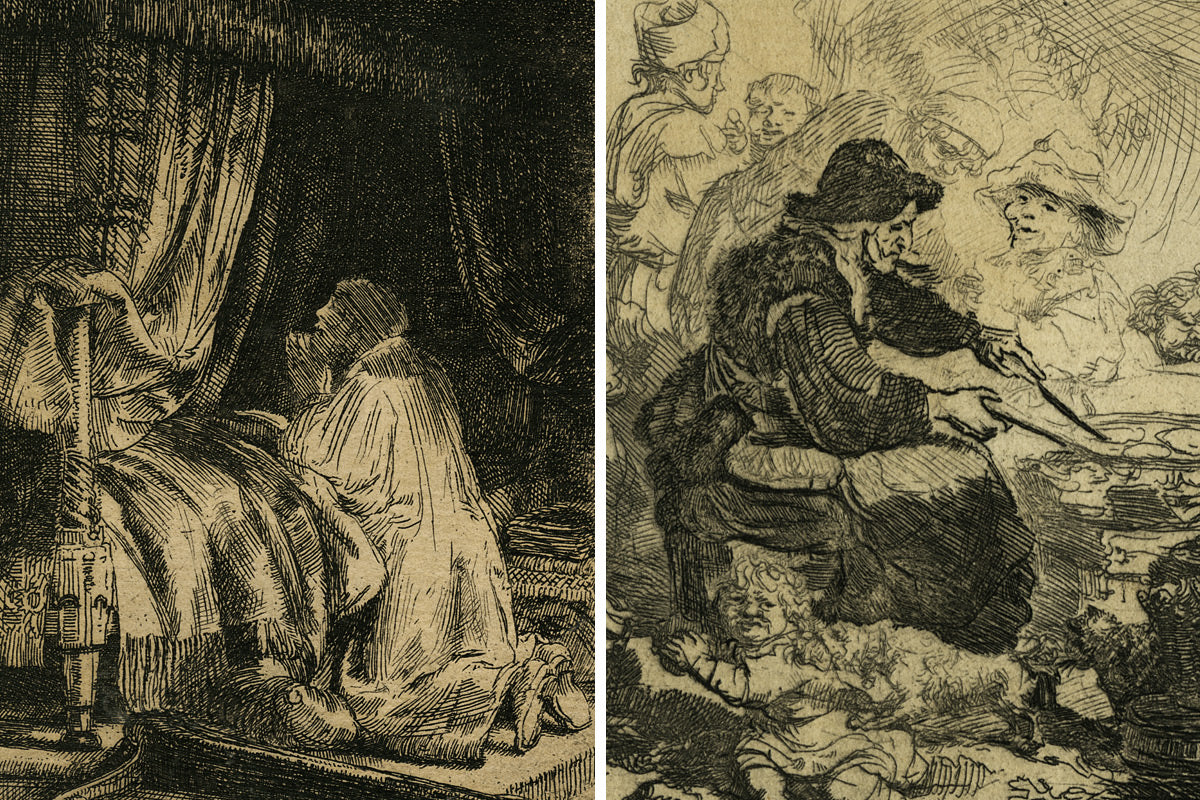

Great praise was given to the treatment of light and shade in these prints, the chiaroscuro effect that he had learned from reproductions of works by Caravaggio, who had first developed the technique. Often Rembrandt's plates would be worked and reworked many times over, the artist constantly fiddling with minute elements to get the breadth and depth of tone he desired.

Bible scenes, bucolic landscapes, urban scenes and exquisitely designed portraits constituted the bulk of his work, which soon made its way into the hands of jealous German and Italian masters unable to fathom how Rembrandt had achieved such effects.

(above) 'Peter and John at the Gate of the Temple'; (below) 'David in Prayer' (left) and detail from 'The Pancake Woman'

(above) 'Peter and John at the Gate of the Temple'; (below) 'David in Prayer' (left) and detail from 'The Pancake Woman'

All would be well, were it not for Rembrandt's extravagance. A keen purchaser of art, even when the auction price outweighed his purse, he was also known to spend vast amounts of money on props, trinkets, and paraphernalia, all for use in composing the next historical painting. Despite inheriting Saskia' sizeable fortune upon her death just a year after the birth of Titus, he was plunged into bankrupty after the Netherlands suffered a major economic depression in the 1650s.

Hounded by creditors, he declared a 'cessio bonorum', surrendering his goods (including a huge number of paintings and prints) to avoid imprisonment. As is expected when an artist's work floods the market, it sold for next to nothing, leaving Rembrandt with little to his name. He died in 1669, six years after the death of his second wife, Hendrickje, and mere months after the sudden passing of his son, next to whom he was buried. No official announcement of his death was made, and the man who had once been the most famous artist in Amsterdam was quickly forgotten.

(above) 'Abraham Francen, Art Dealer'; (below) <'Jan Uytenbogaert, Armenian Preacher'

(above) 'Abraham Francen, Art Dealer'; (below) <'Jan Uytenbogaert, Armenian Preacher'

Fortunately, Rembrandt’s copper etching plates were not amongst the items auctioned off after his bankruptcy, and for a while their whereabouts were unknown. The technical mastery and inventiveness with which he made his 300 or so etchings was already recognised in his lifetime and his prints had been widely sought after.

The very fact that his graphic work could be reproduced meant that it was his etchings, rather than his drawings or paintings, which led to his international reputation at the time. Baldinucci, a famous contemporary Florentine biographer, praised Rembrandt’s highly bizarre technique, which he invented for etching and which was his alone, being neither used by others or seen elsewhere.

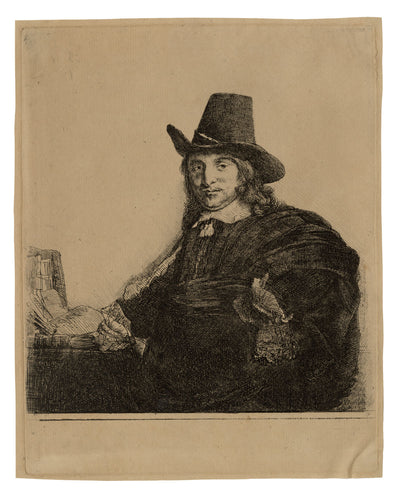

'Clement de Jonghe'

'Clement de Jonghe'

After the artist's death, the first record of the plates appeared in an inventory of his estate created by a friend, the print dealer Clement de Jonghe. The plates then passed through several hands, but it wasn’t until the latter half of the 18th century that the first significant posthumous impressions of the existing copper plates were made under the ownership of Parisian dealer Claude Henri Watelet, himself a highly skilled etcher and apparently the first to rework some of the plates.

In 1786 the Parisian printer and publisher Pierre-Francois Basan acquired around 80 etching plates by Rembrandt from the Watelet estate. The so-called Basan Receuil was first published three years later and constituted a landmark, not only in the history of Rembrandt scholarship, but also in the development of the academic study of art. For the first time a volume containing an overview of Rembrandt’s work, printed from his own etching plates, was available to the collecting public. It was, in many respects, the first illustrated catalogue of an artist’s work.

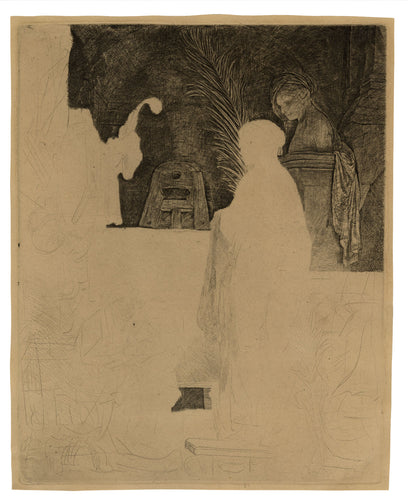

(above) 'The Flight into Egypt: Crossing a Brook'; (below) <'The Flight into Egypt: A Night Piece'

(above) 'The Flight into Egypt: Crossing a Brook'; (below) <'The Flight into Egypt: A Night Piece'

After Basan died in 1797, his son, Henri Louis, inherited the plates and published further collections of Rembrandt etchings between 1807 and '08. The H. L. Basan edition of 78 prints, from which the images in this article are taken, seldom appears for sale, making for one of the most exciting acquisitions the Goldmark Gallery has ever made.

'Self-Portrait in Scarf and Cap'

'Self-Portrait in Scarf and Cap'

It is said that during his lifetime and after his death, fellow artists could not believe Rembrandt had been able to make etchings of the quality he had without the help of some special power, a divinely inspired secret, perhaps, that died with him and would never be rediscovered.

To even the greatest artists of the last 300 years he remains an unrivalled master, as exemplified in Van Gough's famous eulogy: [he] is so deeply mysterious that he says things for which there are no words in any language. Rembrandt is truly called a magician…