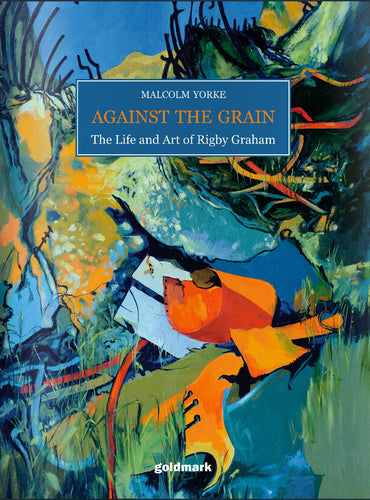

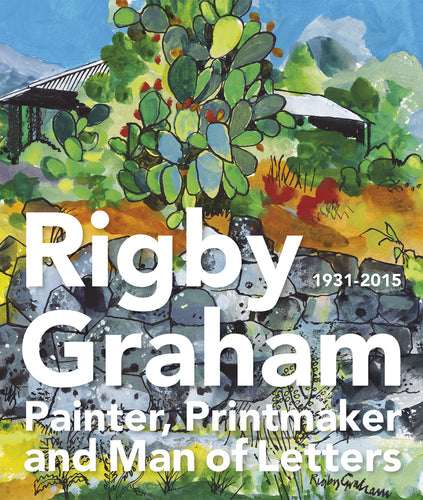

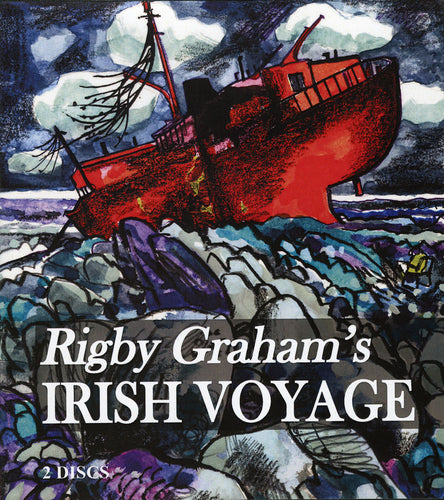

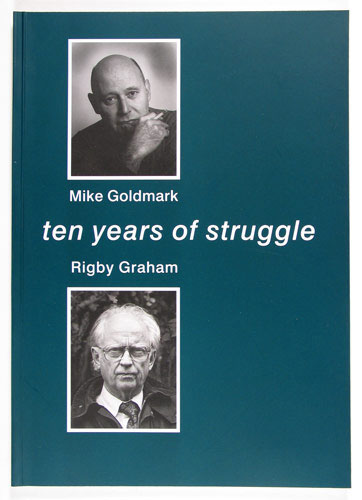

For over 25 years Rigby Graham and Mike Goldmark forged a close working relationship that resulted in several exhibitions, a huge volume of extraordinary work, a feature film of Graham's travels in Ireland, and a great deal of laughter and frustration.

Well known for his scathing wit, unforgiving eye, and his relentless industry, Graham continued to produce work despite his ailing health until his death in May 2015, just months after the launch of our book on his life and art written by critic and biographer Malcolm Yorke.

In this Profile post we look back to Mike Goldmark's words in the preface to Victor French's Rigby Graham: Watercolours of Malta publication, written back in 2008.

In his essay Mike details the start of their friendship, Graham's characteristically prickly temperament, and his outstanding productive legacy.

A Master of his Art

Best of all, I like working with extraordinary people. Over the years, I seem to have developed antennae for spotting them, for the best of them don't come wrapped and labelled and rarely conform to one's stereotypical view of their particular trade or calling.

So it was that when I first encountered Rigby Graham some twenty years ago, he was clad more like an English provincial bank manager than one's idea of a painter. He was browsing in my second hand bookshop in Middle England's Uppingham. Graham is an avid bookman. He reads most of them twice including all the odd bits that most of us skip; copyright notes, indices, appendices, publishing paraphernalia, all devoured and recallable decades later.

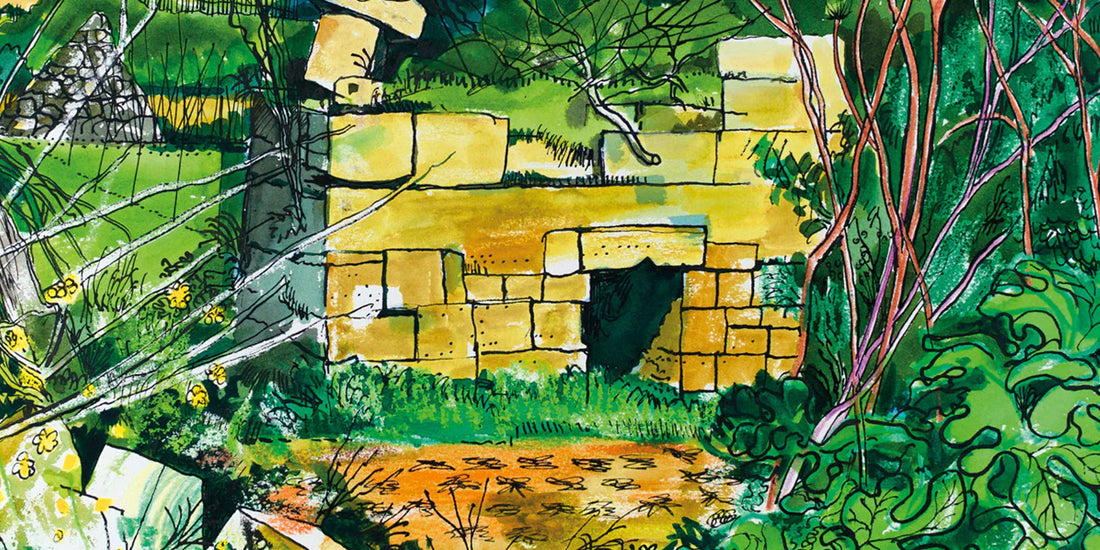

Isle of Wight - watercolour

Isle of Wight - watercolour

He has illustrated hundreds of volumes from broadsheets and pamphlets to full sized books. He has also designed them, written them, set and printed them, even made the paper. His Graham's Leicestershire, heroically published by the late Bill Gadsby in 1980, is a tour de force. For it, Graham made over one hundred and fifty paintings, drawings and prints. His response to Gadsby's request for a little text to go with the pictures was a lively and authoritative 80,000 word essay. As an English county book it ranks with the best of those of the nineteenth century.

Corfe Castle - lithograph

Corfe Castle - lithograph

My first meeting with him proved timely. The building site next to my bookshop in Uppingham was the beginning of my art gallery and that chance meeting was the start of a relationship which has lasted through thick, thin and sometimes thinner, to this day. The letter from him that followed a couple of days later is typical of the numerous others which I have received from Graham over the years, letters which I am sure will one day fill a book of their own:

No doubt you will be inundated with the usual run of local talent, budding artists, people with potential and promise. When all these have run their course you might care to show someone who has no promise and is not worn down by potential and skill, but who produces stuff in anger and bitterness, with hopelessness and vindictive spite. Stuff which is rather too much for most people, is an acquired taste which appeals to the lopsided and the idiosyncratic.

Mycenae, Greece - oil painting(above); Barracuda, Balluta Bay - watercolour (below)

Mycenae, Greece - oil painting(above); Barracuda, Balluta Bay - watercolour (below)

Despite his protestations that I should start with something safer, I opened my gallery with a Rigby Graham exhibition. He was already the veteran of over forty previous shows including one in Malta in 1976. Much to his surprise his watercolours sold well to the five hundred people who attended this inaugural show. Most men would have busied themselves making more of the same to satisfy the market; but not Graham. For the next two years he worked on the series of large woodcuts that we had premiered at the show where one only had sold, albeit to a director of the Tate. If they are not selling, he said, then they must be alright.

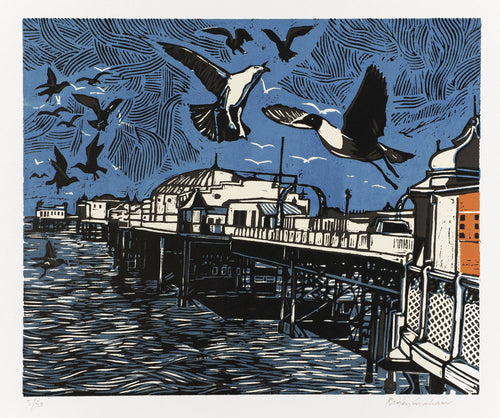

Balloon Race - woodcut (left); Minotaur - linocut (right)

Balloon Race - woodcut (left); Minotaur - linocut (right)

This is not to suggest that Graham is independently wealthy. But he is fiercely independent. I suspect that there have been times in his life when things were not easy but I have never known him compromise his work in any way for financial gain. More than any man I have ever met, he manages to separate the art that he devotes his life to, from the business of making a living. The two things live in different boxes; the first an obsessive drive, rarely if ever satisfied, the latter a necessity often viewed with seemingly Zen-like indifference or vague annoyance.

Standing Stone against a Stormy Sky - watercolour

Standing Stone against a Stormy Sky - watercolour

He still expresses surprise when I phone him to tell him of a sale. He may ask what possessed the purchaser to buy that particular piece but never ever how much they paid. Commissions are rarely accepted and then only on the understanding that no money is charged up front and that there is no obligation to purchase. Graham thereby leaves himself free from the need to please and although he is happy if the resultant work is liked, this method of working ensures that his artistic integrity remains perfectly intact.

Big Foot, Malta - linocut (above); two woodcuts (below)

Big Foot, Malta - linocut (above); two woodcuts (below)

And in all that Graham does, it is integrity that is key. A job will take and be given as long as it needs. Nothing is skimped, everything finished to the very best of his ability. Any principle of cost effectiveness is a complete anathema to him. Yet, despite what sometimes appears to be a somewhat laborious way of going on, his output has been extraordinary and even now, at the age of seventy five, his work rate would put many men of half his age to shame.

The White House, Moscow - linocut

The White House, Moscow - linocut

This way of working has made Graham a master at whatever part of his art he focuses on. Whether it is in book illustration or the making of woodcuts or linocuts, lithographs or etchings or even designing stained-glass windows, he has a real understanding of process and this combined with his special way of seeing produces art of real quality.

Castle Hill, Hallaton - watercolour

Castle Hill, Hallaton - watercolour

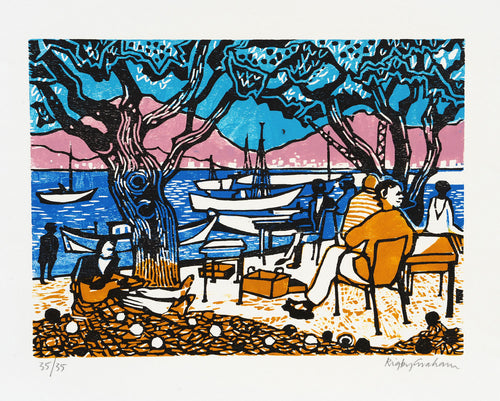

But first and foremost, Rigby Graham is a landscape painter. He has both a love of landscape and a real understanding, returning to it constantly. He treats it with both passion and compassion. It still thrills him to look and sit and paint, which he will do in all weathers only stopping if the rain is washing his paint off faster than he can apply it. He has looked hard and recorded for us what we have done to the landscape, how we have often damaged it, and how it, in its turn, slowly but inexorably removes and destroys our strivings allowing all things to revert to what they were. He has returned again and again to those places that inspire him. Ireland is one such, Malta another.

Manoel Island, Malta - watercolour

Manoel Island, Malta - watercolour

Unlike so many artists who use watercolour, Graham paints with the colour and not the water, producing powerful glowing pictures rather than the washed out efforts of so many lesser practitioners. And unlike so many of his fellows, he shows us the world as it really is although the view might surprise or even sometimes disturb us. While he will often confront his subject matter full on, a tower, a castle, a ruined church, he is just as likely to have wandered round the back and will show an angle that few would have contemplated. We will also be shown what was really there; the detritus with which we have littered the landscape, the road signs, telegraph poles, barbed wire and bedsteads.

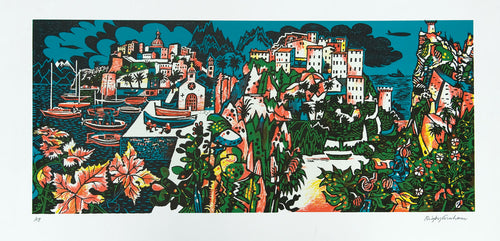

Mountain Village, Corsica - oil painting

Mountain Village, Corsica - oil painting

I bought my first Rigby Graham painting twenty years ago and it still continues to move me and give me pleasure. But even more than that, owning and looking at his work has helped me to see the world with a greater clarity and through that an increasing understanding. I can think of few more important gifts that a man could bestow on his fellows.