Ruth Smoking II

There are few places where Julian Opie’s art has not been: giant billboards; LED screens in airport waiting lounges; CD covers; road signs. He paints on steel sculptures. His line drawings become animations, become advertisements, become full-scale models and monumental office-block illustrations. Traditional art boundaries mean little in his world of minimal faces and spaces.

Born in London in 1958, Opie studied art at Goldsmiths College in the early 1980s. This was a time of fragmentation in the art world: truth and originality were deemed dead and gone, subsumed by a pervasive anti-establishment fervour. Though he began his career at Goldsmiths locked away in life-drawing classes, Opie recalls how the restless atmosphere soon propelled him into sculpture, film, model-making, and the blending of ‘high’ and ‘low’ culture: Our attitude towards art history, towards schools, styles, and "isms", was quite aggressive. We wanted to manipulate them, to use whatever style we wished.

Julian with Cardigan

Julian with Cardigan

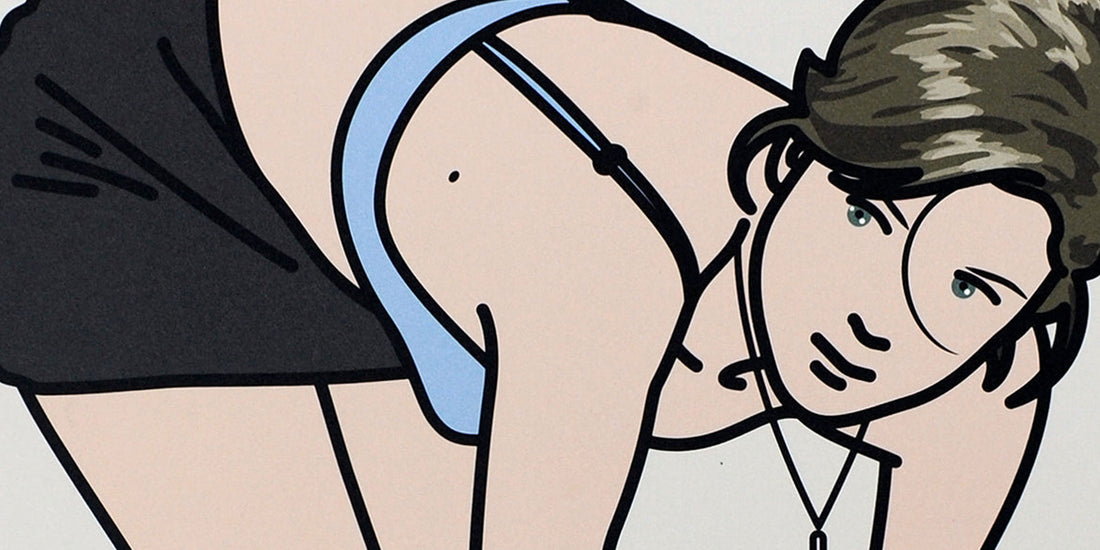

A key technique that informed much of Opie’s work, and which is embodied in these screen prints, was the reduction of recognisable features to their barest and most essential. Early experimentation with animated drawings manipulated art like a lens, taking the individual features of a profile and subjecting them to an art-historical style: It was just a portrait of someone’s head but I turned it into an inventory of styles; so it would first be sharp-edged and spiky, like a Futurist portrait, and then it went soft and classical, and then it would become broken up and Cubist.

(left) Hijiri with Umbrella; (right) Shahnoza with Beads

(left) Hijiri with Umbrella; (right) Shahnoza with Beads

In these later portraits, each face is reduced to only the most easily identified of aspects – a hairline, or a brow – until the impact of the image becomes immediate. The result is almost paradoxical: on the one hand, each portrait is distinct and distinguishable from the next, capturing the essence of its subject; yet on the other, elements are stripped back to the extent that these images are matter-of-fact, universal. They are pictures of a specific somebody; and yet they could almost be pictures of anybody.

Hijiri with Veil

Hijiri with Veil

What has characterised Opie’s work, from reactionary student days to these 21st Century prints, has been openness and access, both in the image and the context in which it is placed. His best-known work, the cover art for Blur’s seminal Greatest Hits album in 2000, was distributed and viewed on millions upon millions of CD cases; those same band member portraits now also reside in the National Portrait Gallery.

These screen-printed faces relay the same message, from generic outlines to the most particular of expressions: his is an art for all people and all places.