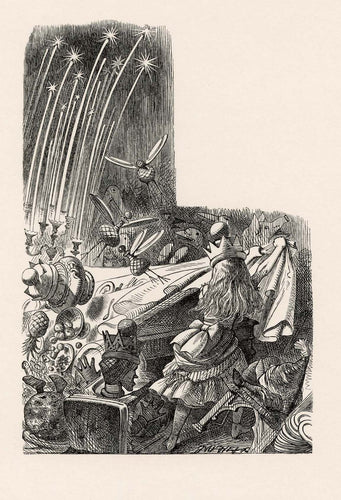

Iconic images of wit and wonder, Sir John Tenniel’s illustrations for Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass are as magical today as when first published a little over 150 years ago.

An amateur artist himself (and, by all accounts, something of an egoist), Lewis Carroll had originally intended for his own illustrations to accompany his extraordinary text of Alice’s tales, and it was not without delicate persuasion by the author’s friend of his artistic deficiency that Carroll sought out a professional draughtsman.

John Tenniel, lead cartoonist for the politically mischievous Punch magazine, had already established a reputation for classical precision in his sketches, in which humour, composition, and execution of the image were treated with equal respect. A keen reader of the publication, Carroll knew his work well, and before long the pair had agreed on a collaboration.

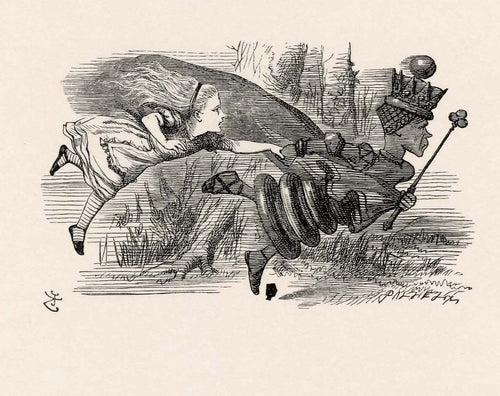

Initially, their working relationship was fractious. A stubborn Tenniel found Carroll’s constant interjections during the first drafts of the illustrations tiresome and, as Carroll later revealed in correspondence, was unafraid of saying so: Mr Tenniel is the only artist, who has drawn for me, who resolutely refused to use a model, and declared he has no more needed one than I should need a multiplication-table to work on a mathematical problem!

Eventually, and despite Carroll’s insinuations, Tenniel completed the 92 images to accompany both the author’s texts, drawn directly onto their boxwood printing blocks. So involved was the artist with the project that, upon its momentous completion, he seemed drained of further inspiration. Tenniel undertook almost no work in the subsequent years that led to his celebrated knighthood (the first for an illustrator) in 1893.

When asked by Carroll to aid in a second project, he declined with the revelation that …It is a curious fact that with ‘Looking-Glass’ the faculty of making drawings for book illustrations departed from me… I have done nothing in that direction since.

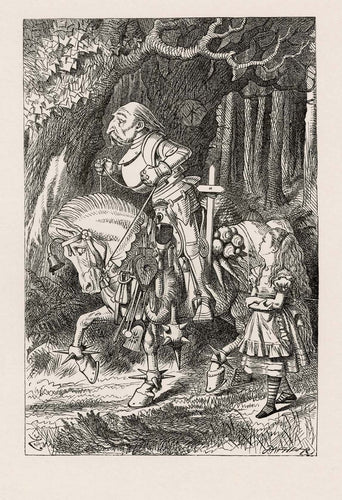

The cutting of the blocks was undertaken by the ubiquitous Dalziel brothers, master engravers of the Victorian age who had worked alongside some of the 19th century’s greatest artists, notably the Pre-Raphaelites Millais, Rossetti, and Burne-Jones. Supervising their workshop of skilled apprentices, the Dalziels oversaw the preparation of the blocks with Tenniel himself, whose exacting standards demanded subtleties of line and nuances of shading in every facsimile before giving his consent to print.

So fine were Tenniel’s lines, however, that the engravers feared the blocks would deteriorate before the large-scale printing of the books had been completed. They advised instead that these should act as the masters from which electrotype copies could be produced. These metal blocks would withstand greater numbers of printing runs, but at a subsequent loss of definition and tone.

Exactly what happened to the original blocks in the decades between their casting and eventual rediscovery remains a mystery. Fortuitously, they appear to have been closely guarded, even to the point of relocating the blocks from London to a Suffolk print atelier throughout the Second World War, avoiding their potential destruction in the bombing runs of the Blitz.

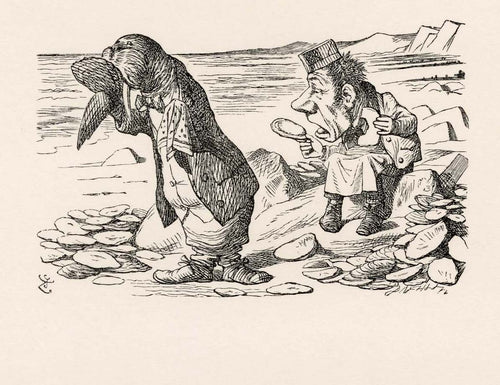

Of the original 92 woodblocks, only one has been lost: Alice and the Dodo, the sole illustration of this later set to have been produced from the surviving electrotype copy. How apt that it was the Dodo, of all the characters in Carroll’s menagerie, that was destined to disappear.

In 1985 the original wood engraved blocks were found in deed boxes belonging to Macmillan, Carroll’s publishers, secured there by the publishing house’s post-war Art Director (whose name, by yet more bizarre coincidence, was also Lewis Carroll). Jonathan Stephenson of the renowned Rocket Press was awarded the prestigious task of printing 250 sets from them, the very first time that they had ever been used besides their initial proofing. The edition would be distributed worldwide and no further sets commissioned.

Cut with pristinely clean, clear lines, the sheer quality of the wood engraving passed seamlessly from block to paper. As Dr Leo John de Freitas, leading authority on book illustration, has noted, the partnership between Tenniel and the Dalziel studio produced a definitive feat of printmaking: In the tremulously - as in the overtly - engraved passages of the Alice blocks there is a sculptural quality in which the refined craft skills that turned the beautiful sections of highly polished boxwood into fine printing surfaces can be experienced…These blocks are a delight to examine…

Tenniel’s greatest and most enduring achievement, the Rocket Press’ reproduction of these illustrations from the original woodblocks restores a richness and clarity unachievable in the electrotype prints. Having stood the ultimate test of time, ranking even to this day among the world’s best-known children’s images, they will no doubt continue to delight for generations to come.