The French call their traditional slipware terre vernissée – ‘glazed earth’. It’s a poetic phrase that really has no English equivalent, distilling the fundamentals of pottery to a lyrical minimalism of two words: la terre, the very ground from which the potter’s clay is unearthed; and le vernis, the silky veneer of slip that glazes the earthenware body beneath.

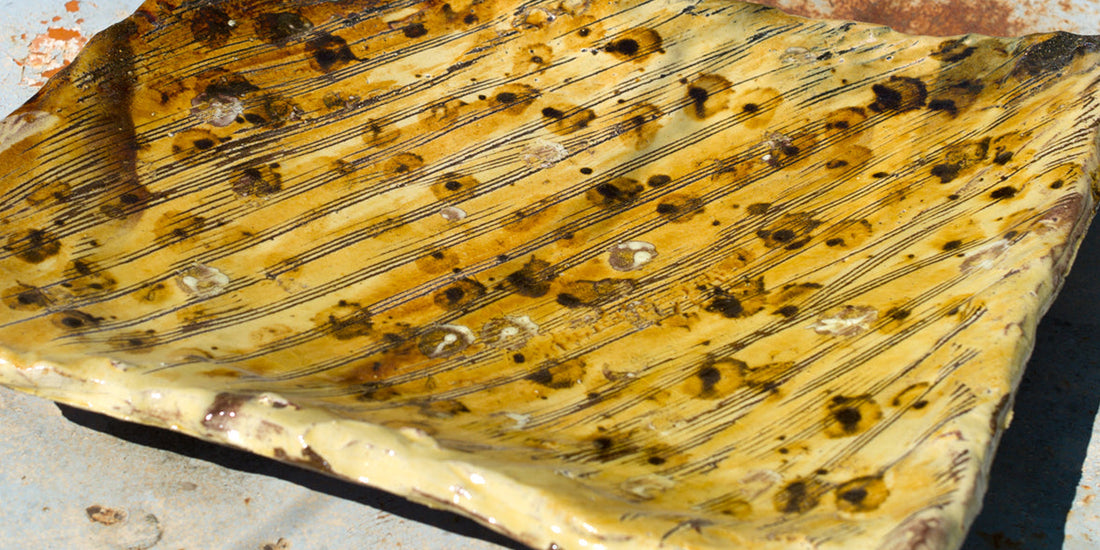

Both terms find their fullest expression in the pottery of Jean-Nicolas Gérard, and most especially in his giant square platters. Clay is essentially mutable stuff, permitting innumerable metamorphoses, but in Gérard’s pots his rich red clay is made to look as if freshly dug from the Valensole hills. These huge dishes, with rumpled, up-turned edges, become vineyards or lavender fields in miniature: sgraffito scars mimic row upon row of grape vines; blue-green finger spots suggest clumps of flowers awaiting their lilac blooms. Around their edges, glaze often breaks to reveal arid red clay beneath, a dusty imitation of the crumbling slopes that irrigate the local estates.

But it is Gérard’s glorious manipulation of slip, more than anything, that bears out on these square dishes. Some are cloaked in a thunderous black slip, the hot, smoky, black of a Provençal night. Others glow with bright yellow, a sheen that dips into Gérard’s undulating surfaces, blooming into patches of deep gold or glistening with bitter lemon.

detail of a large square platter, revealing both its mottled breadth of colour and the scarred landscape of sgraffito lines

detail of a large square platter, revealing both its mottled breadth of colour and the scarred landscape of sgraffito lines

There is an obvious temptation to compare these giant square dishes with the Abstract Expressionism of the likes of Jackson Pollock. Like Pollock, Gérard ‘attacks’ his platters on the floor, pouring slip over slabs with an old saucepan, jabbing into the clay with fingers and thumbs.

Jean-Nicolas Gérard dabbing spots of slip onto the surface of a square platter

Jean-Nicolas Gérard dabbing spots of slip onto the surface of a square platter

It is decoration with all the vigour and spectacle of the theatre, the square slab of clay his ceramic stage - and yet it is all done without pretence, with so little self-awareness or need to impress; each sgraffito line, drawn with the artful assuredness of a Matisse or a Picasso, is carved with the humblest tool of a rust-tipped teaspoon.

This is the double life that Gérard lives: ‘I think I am like an old artisan,’ he says modestly, and in his truth-to-materials approach to clay this is true; but his work has the sculptural and painterly heft of a major artist. These large platters embody that duality: with wires affixed to their backs, they can be hung on the wall, an abstract ceramic canvas that conveys a magnificent sense of landscape. Unhook them and place them on their four lumpen feet, they transform into a communal space, a platter for shared food and good company. In the face of Gérard’s pots, the eternal questions of form versus function, art versus craft, seem so very meaningless.