One of the very first fine art prints I ever owned was a little lithograph by Joan Miró. It hung on my bedroom wall from an early age – perhaps six or seven years old – and quickly became my favourite picture in the house. As I sit writing now, some two decades on, it hangs in front of me again, caught in a sliver of yellow light from an adjacent window.

At its centre is what looks like a kneeling figure, two short, truncated legs folded below a swirling, circular body shaped like a Catherine wheel, spikes of black ink jutting out like spines across its back. In the background fireworks of colour pop in the distance – orange, deep green and purple. For years, I took the two, squinting ovals conjoined above the circle to be its eyes. He became my Miró monster, greeting me as I woke in the morning and again as I returned from school.

Then one day, as I walked back into my room, I glanced over at this ludicrous little creature of brushstrokes and colour and saw something entirely new. The eyes were not above now but within its body, two staring black dots that I had seemingly never noticed before. There were in fact now two creatures: the round, squat, kneeling character and a strange spider-like insect perched atop his head who took up the eyes above for himself. Try as I might, like an optical illusion that suddenly reveals itself I could not ‘unsee’ this change in my monster, and from that day on he gained a new companion.

It seems an entirely ordinary experience to look back on with such vivid memory, but that moment in which an image I had seen countless times changed before me taught me two important lessons. The first, that in great art you can never stop seeing new things – and this is especially the case with an artist like Miró, who blended figurative, symbolic and abstract worlds with such ease. His work delights in constant reappraisal, revealing in his kaleidoscopic prints and paintings forms that seem to metamorphose and merge between one another.

It also taught me something of our fundamental need when presented with abstract images to find something familiar, discernible, and of the world we recognise. It can be almost guaranteed that the first thing any pair of people presented with a work of abstract art will do is compare what they see in its forms: a house, perhaps, with a little roof; no, a sea, surely? It is an instinctive reaction that is so deeply ingrained in our minds that it can be difficult to ignore.

The near-universal popularity of Miró compared, for example, to the controversy that still surrounds the splatter paintings of Jackson Pollock or Rothko’s coloured squares, is no doubt due to the fact that there are precisely such observable things in his work: stars, red suns and moons, women and birds, planetary constellations and bug-eyed creatures of the night. ‘Everything comes from the visible’, he once told the art historian Walter Erben: ‘There is nothing abstract in my pictures.’

What then of the artist himself? Born in Barcelona in 1893, he was a friend and contemporary of Picasso, a one-time Surrealist, Magic Realist, dreamer, and, above all, a Catalan. Though he spent much of his early career in Paris, the landscape of Cataluña, in particular the sun-baked mountain ranges of Tarragona and the family summer home in Montroig, permeates his work from early, part-Fauvist part-Cubist paintings of Catalonian farmhouses to the electric abstract compositions of the 1950s and ‘60s.

His flirtation with Surrealism never fully consumed him, despite André Breton’s remark that he was ‘perhaps the most ‘Surrealist’ of us all’, and though it provided a strong poetic grounding that reveals itself most clearly in suites like his illustrations for Alfred Jarry’s bizzare comic play Ubu Roi, Miró sought a more personal artistic path.

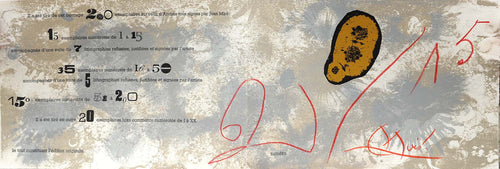

'La Revue', illustration for Jarry's Surreal play 'Ubu Roi'; unusually, this is one of a series printed without the black key plate, and so lacks the usual black outline

'La Revue', illustration for Jarry's Surreal play 'Ubu Roi'; unusually, this is one of a series printed without the black key plate, and so lacks the usual black outline

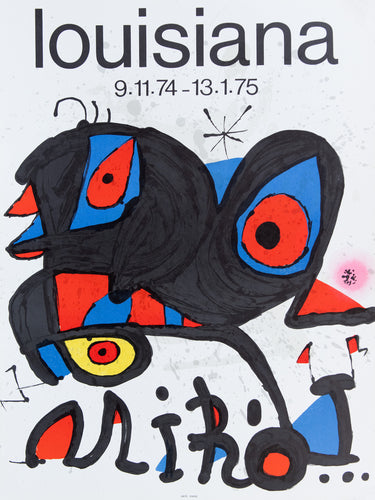

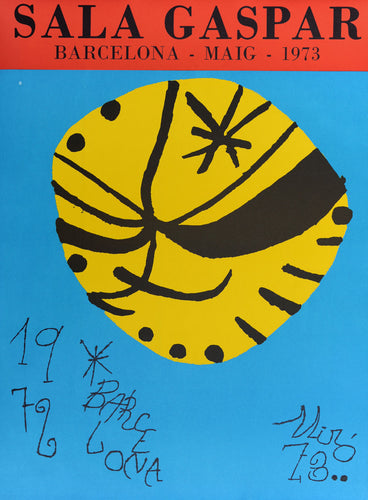

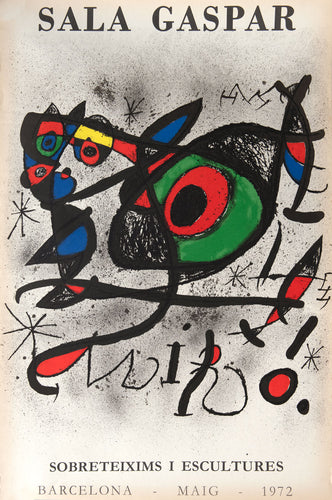

Over a long career he developed a rich, complex symbolism that was quite his own, a visual language made up of recurring shapes and figures and a calligraphic touch that really has no equal. He liked primary colours best – black, cadmium red and yellow, and cobalt blue – yet, despite his limited palette, produced a phenomenally prolific output of work that never feels tired or repetitive, but which sings with boundless energy.

As I continue to look and to write, Miles Davis’ Sketches of Spain, the jazz trumpeter’s inspired rearrangement of Rodrigo’s Concierto de Aranjuez, begins to play in the background. I find myself drawn to the parallels between Miró and Davis, whose exquisite tonal range, from muted, silver whispers to full-blown, brassy blasts of colour, seems to resonate with Miró’s work.

Davis’ strength, like Miró’s, lies in an ability to do so very much with so little. Short, repeated refrains are spun one after the other, often trilling around just a single note. Miró’s repertoire of forms was likewise comparatively small – star maps, small, spirit-like, primitive people, wandering lines and pure blocks of colour – and yet the essence of each composition is much its own, the harmonies and dissonances between individual elements delicately balanced with a different rhythm in each new arrangement.

an extremely rare set of prints, including a unique trial pull on newspaper (middle), accompanied by the original blocks from which its two small editions were produced

an extremely rare set of prints, including a unique trial pull on newspaper (middle), accompanied by the original blocks from which its two small editions were produced

Like Miró too, Davis was unafraid of empty space, of the palpable silence that gave power to the re-emergence of each new string of notes. Miró’s dancing figures and symbols are frequently given free rein to float and vibrate on their own, suspended on paper and canvas like the sonorous blots of paint that fell when he cleaned his brushes in his studio and which endlessly fascinated him.

The more I listen, the more I look, the more tempting it is to push the connection – to see in the Odyssean, dreamscape tracks of Davis’ Bitches Brew echoes of the vibrant, voodoo colour of Miró’s last paintings, or to apply the clever wordplay of Kind of Blue to the artist’s famously despondent disposition. But in truth, Miró is one of few artists for whom the act of comparison and contextualisation often feels pointless.

There was no real equivalent, contemporary vision to match his peculiar straddling of the worlds of Surrealism and Abstraction. Placing the works of others beside his proves a fruitless task as they pale – quite literally – in comparison with his dynamism, the childlike vitality of his use of form and line. One would do best with Miró’s work simply to look and keep looking: there is food enough in this feast of colour.

staff pick courtesy of Max, gallery writer and editor