The late Stanley Jones will be remembered as one of the key figures in the revival of British post-war printmaking. Here we look back at an extraordinary life.

The role of the ‘Print Master’, as a 2012 BBC Radio 4 programme styled the late Stanley Jones, is not an easy one. Rarely is an encyclopaedic knowledge of the craft, a mastery of colour, or an eye for precision enough. To guide the work of an artist from start to finish – often an artist who has no prior experience of the medium at hand – requires patience, compassion, dependability. More than inspiring trust, the master printer has also to balance technical prowess with artistic sensibility: to really see what an artist is doing and understand where they are headed – or, perhaps, point them in the right direction. You have to be like water: adaptable, fluid, and un-corrupting. To be welcoming, while knowing when to take charge and step in. In short, to be for many artists many different things: teacher, midwife, co-conspirator, port in a storm.

Stanley Jones and Peter Baer take an impression from a zinc plate at the Curwen Studio, Midford Place, c. 1960

Jones, who died earlier this year, was all these and more: a consummate mediator whose vast legacy is evidence of an enviable combination of vision and humility. A trained artist in his own right, which developed the open mind necessary for the position, as director of the Curwen Studio he brought British lithography to a level of quality and respect equalled only by the grand ateliers of Paris. It was here, funded by two scholarships from the Slade, that he had served his own apprenticeship. In 1956, the enigmatic etcher S.W. Hayter introduced him to the lithographer Gérard Patris, exposing Jones at the earliest stage of his career to some of the most experimental and innovative printmaking then happening in Europe. Young age, stamina and creativity, combined with his experience, made him the perfect choice to establish an equivalent atelier in England, and the Curwen Press – long home to artists since the oversight of Harold Curwen and Oliver Simon – the ideal parent company. The dealer and publisher Robert Erskine approached him late in 1957 with the offer of overseeing the new studio. To add to his sensitivity to the stylistic possibilities of the medium, Erskine saw in the young Jones the ‘obsessive cleanliness’ that would ensure professionalism at every step (one of Jones’ habits, his children later recalled, involved touching a bar of soap every time he left the house).

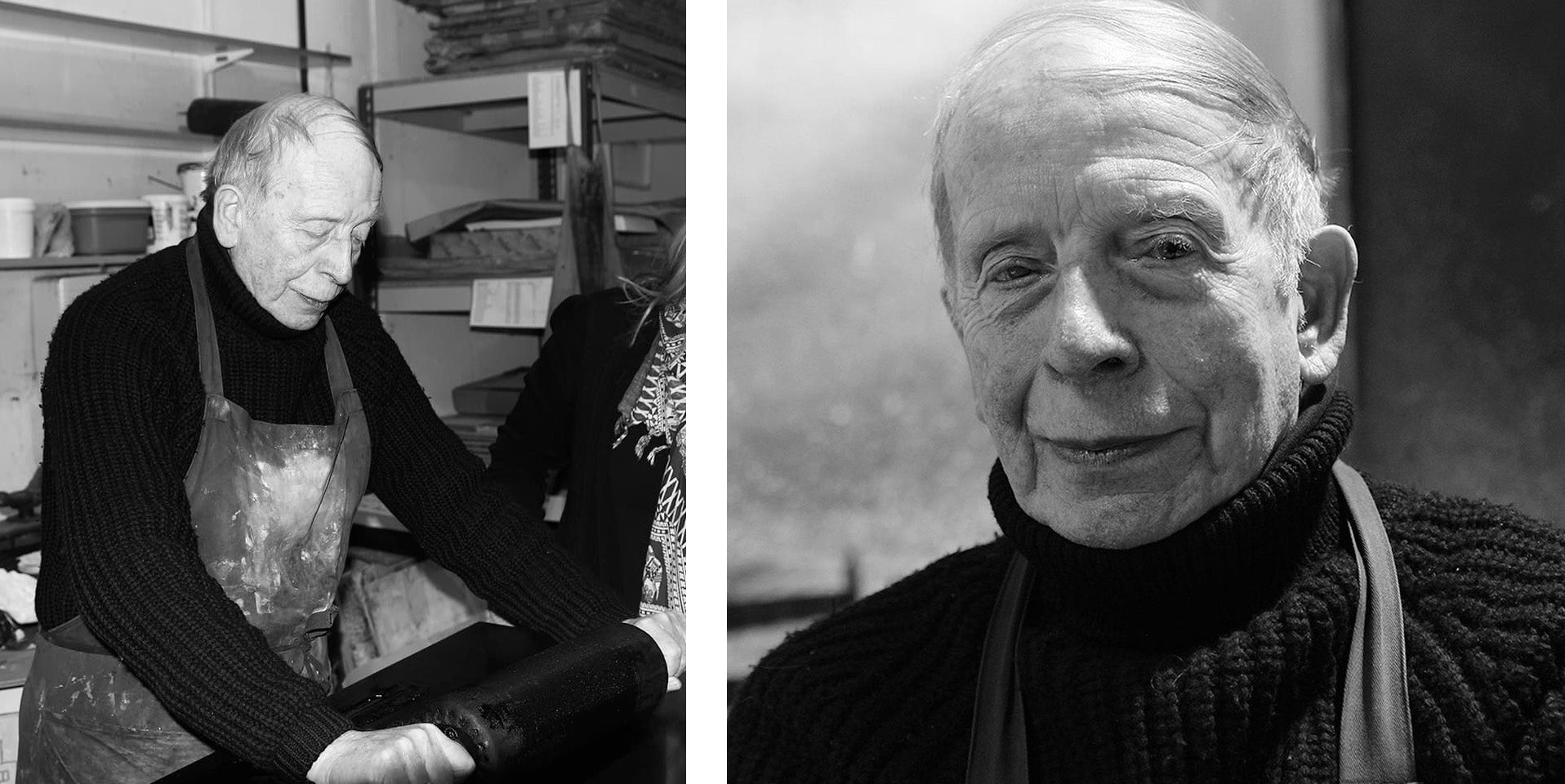

Stanley Jones at the Curwen Studio, photographed by Petra Stenvall

There was at that time no obvious market for original artists’ prints in Britain, no industry of independent publishers and few enterprising gallerists waiting to move into this new territory. Curwen Studio was an enormous gamble, for all involved. Thankfully Jones accepted, and their pioneering paid off. The London premises, however, would take some time to outfit, so Jones was sent as a kind of print missionary to St Ives, tasked with establishing a temporary studio there and seeking out partnerships among the Cornish town’s hive of artists. Here he had the unenviable task of navigating the choppy waters of competing artists’ cliques (Barbara Hepworth and Peter Lanyon, he was told, were not to be allowed in the same room). But drawn to abstraction himself, he was able to meet each on common ground and bruisable egos were quickly soothed. These earliest collaborations with the likes of Patrick Heron and Bryan Wynter proved there was sufficient appetite – among artists themselves, at least – for serious explorations in print.

Stanley Jones at Curwen Studio, photographed by Petra Stenvall

Established first on St Mary’s Road then, from 1965, in a large subterranean space off Tottenham Court Road, the Curwen Studio was to do for home-grown lithography what Chris and Rose Prater’s Kelpra Studio was achieving simultaneously with screenprinting, opening its doors to enthusiastic (and irreverent) young British artists and recognised masters keen to explore new avenues (an expired lease in 1989 saw the atelier relocate to Cambridge). Like contemporaries Paolozzi and Peter Blake, he was an incurable collector of ephemera, with a curiosity for almost any aesthetic, whether ‘high-brow’ or cheap and cheerful. His personal collection – where marmite jars and a Cadbury Crème Egg novelty mug rubbed shoulders with watercolours by John Piper and Mary Fedden – is matched only by the list of names who worked alongside him. Piper, Sutherland and Bawden provided continuity Curwen from their work before the war, while the newer generation of David Hockney, Alan Davie, Prunella Clough and Paula Rego soon took to the medium. He established a particular rapport with sculptors, among them Hepworth, Moore, Butler, Armitage, Chadwick and Frink, each drawn in different ways to the tactile quality of stone and metal plates. Tact and management were necessary when dealing with less attentive artists: Colquhoun and MacBryde, gripped in the spiral of alcoholism that ruined them both, had to be hunted down and dragged, thoroughly soused, from nearby pubs to finish their work. And, with rather touching circularity, in 1971 he found himself printing the very last works of Ceri Richards, bringing the plates to Richards’ bed and placing them in his hands of the teacher who had inspired his experiments with lithography at the Slade and been the first client of the nascent Curwen Studio.

Stanley Jones proofing lithographs with Henry Moore, at Curwen Press in the early 1960s

That Jones had such incisive vision from a young age, paired with the instinctual understanding of colour so vital to lithography, perhaps came as a surprise to his parents: he was blinded at birth in one eye by the doctor’s forceps (a condition that cannot have helped with registration on the press). But the enduring image of Jones from the accounts of others – his champions included Hepworth, Piper and William Scott – is of enthusiasm tempered with extraordinary patience: painstakingly gluing feathers of Japanese straw paper back together for Ceri Richards, mopping up John Piper’s ‘blizzard and scree’ textures and trials in marbling on transfer paper, and ironing more ‘experimental’ transfers to the stone blocks on which his reputation was made.