Wood-fired jars by Svend Bayer line up, awaiting delivery to the Goldmark Gallery

Defoe’s simple lesson – you don’t know what you have, until you haven’t – I learned on return from college after my first term, having lived alone for three months. Pots, thousands of them, were everywhere in our home. We lived with them, ate from them, knocked them over as children and stashed stolen empty chocolate wrappers in them when we thought we’d been rumbled. They were a simple fact of life; so much so, that I never really noticed their presence. So when it came to leaving for the first time, the small and inexplicable emptiness I felt living in my dormitory room, bereft of any pictures or pots, I could not ascribe to any particular loss.

It was only on arriving home, by way of the Goldmark Gallery, that I came to realise what I had been missing all along. There, arranged on raised benches and shelves, was row after row of pots by Svend Bayer for an exhibition in 2012. A flood of recognition hit me, and I spent a whole day quietly walking from shelf to shelf, reacquainting myself with a world I had forgotten without knowing it. Bayer had struggled for the show, and the pots there were hard won; several prior firings had major failures, some with up to three quarters of the yield lost. But what he had achieved, agreed Gil Darby, late curator of ceramics at the Victoria & Albert Museum, matched the finest Sung Dynasty pottery held in international collections. I remember being struck by two successive thoughts: these are perfect pots; where on earth do you go from here?

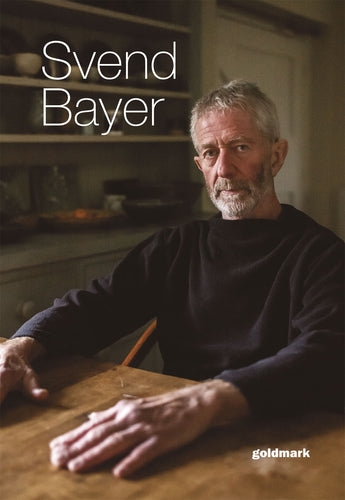

I didn’t know the answer to that question; nor I think then did Bayer. Most makers are content to chase perfection, but few are confronted with following or repeating it. Eight years is a long time, however, and they have not passed without change. Gone are Duckpool Cottage and the kiln sheds near Sheepwash, Devon, built by Bayer’s own hand and where he had been based for many years. He is now to be found heading the kiln team at Kigbeare Manor Farm, 10 miles south. Three years ago, Bayer led the team in building a huge new wood-firing kiln, based, he notes a little wearily, on ‘the easiest kiln I’ve ever had to fire’, and which has continued to defy all expectations of simplicity and cooperation.

Svend Bayer celadon jar

Bayer, like Crusoe, is a loner (self-professed); and that is about where the comparison ends. Of Crusoe’s megalomania, his delusions of grandeur, his mercantile coldness, or his ability to lay ownership to all that he meets, there is none in Bayer, save only a certain amount of canny pragmatism and a quiet single-mindedness that anyone castaway, whether by choice or accident, would be glad of in their maroonment.

But there have been many times when hearing about Bayer’s work that I have been reminded of that little canoe boat, dragged off into dangerous waters. Most recently, he described his difficulties firing through early winter for his upcoming Goldmark show, which our lucky film crew of two were party to. The torrential rains of October and November had cooled and dampened the chimney stack, preventing air from drawing properly through the body of the kiln and killing any temperature rise. Reminded of a similar predicament in the past, he kindled a small fire in the chimney to help dry it out and increase the draught. The temperature rise resumed, unabated, until the very last, and most critical, push of the firing. He knew, at the back of his mind, that there had to be an explanation: exhausting all possibilities, and now visibly worried, the team thankfully discovered that a damper at the back of chimney had not been pulled out – ‘like driving with the brakes on,’ Bayer remarks – and the problem was solved.

All that work, all that time invested, resting on a moment; and in that moment, on a single decision. How attractive must those prior weeks of mixing cold, caustic glazes, or stacking shelves, or splitting wood, seemed when, at first, an answer eluded them.

Svend Bayer firing the kiln

Bayer’s firings are uncommonly long, and all-consuming: a week packing, a week before that glazing, and a kiln firing that is now on average 110-120 hours – five days, split between a team of three working four hours on, eight hours off. By the end of the firing, Bayer says, you are totally disoriented; particularly if, like him, you are happy to take the unpopular early morning shift of 2 to 6am. Once begun, there is no stopping the kiln: no breaking, no interruption, no taking it slow or speeding up for convenience. Time is the ultimate arbiter. If you want the kind of extreme atmosphere of reduction and oxidation Bayer prizes, extracting the very most from the wood ash and a simple palette of glazes – celadons, kaki, and raw clay – you must plot your course and stick to it: a steady, but inescapable, temperature rise charted on a graph.

Firing, like navigation, though at its basis a mathematical art, is not an exact science; its apparatus only rudely calculable. Like any mariner, Bayer is at the mercy of weather and other variables beyond his control. But though in the past Bayer has said he does not enjoy the firing process, he does take to command of it naturally – not command of an authoritarian kind, but something closer to that of a veteran skipper: feeling the currents, adjudging present course, through an unconscious combination of gut, experience, and well-trained prognostication. There is clear-cut physics, chemistry and fluid mechanics to the behaviour of his kiln, like any other: a huge, long, round-vaulted chamber, like the big upturned underbelly of a ship (I find that Tim Gent, in 2012, described him building kilns by sight, rather than measurement, ‘in the manner of a good traditional boat builder’; and that Sebastian Blackie thought his Duckpool kiln swollen ‘like a whale’); but underneath the bones of it all, as the trio begin stoking, Bayer ever alert to developments in atmosphere and pressure, you do feel as if you are watching them fighting a greater force, like the fateful currents under Crusoe, always threatening at any minute to draw them off course.

Wood fired Svend Bayer jug

A firing, however important to the potter, is only the culmination of weeks, and usually months, of preparation and labour. ‘Traditional’ pottery of this kind demands a relentless working pattern: throw, glaze, fire, with all the day-to-day activity of studio and resource management in between. The upshot of that unremittingness is that writing on what is, in ceramics’ broader scheme, a relatively narrow corridor of pottery becomes ever more difficult. We fall into our own working patterns: how difficult the life of a potter is; what dedication, what commitment they show to their craft; what differentiates their chosen vein of pottery; what individuates a maker from that chosen ‘tradition’.

On this last point at least, Svend Bayer makes it easy, because there really isn’t anyone making wood fired pots like his – certainly none that are alive. His peers, if there are any, are those anonymous makers of imperial China and Korea; thousand-year legacies whose spirit Bayer has channelled into his five decades of work, without it ever feeling like anybody’s but his own.

Where he has established a particular reputation is in the making of big pots. For a long time now it has remained central to his working practice; a kind of meditation in action, limited only by whether he can move his labours by himself, since he has more often than not been working alone. This obsession – if he would let me call it that – began under the vigilant eye of Michael Cardew, with whom Bayer spent three emphatic years at the very start of his career, and who quickly realised the indefatigable talents of his ward. Cardew, too, liked to make big pots; and he was generous enough to let Bayer not only make, but also occasionally fire his own large work after showing him how to properly coil from a thrown base.

At 73 (you would not think it), the weathering to his body by years of what has been, effectively, hard labour now finds him at the end of this journey. Making the pots, as he points out, is easy enough; but moving them is another matter entirely, and though naturally fit he is a slight man: ‘I can’t use brute force; I’ve got to kind of think my way around moving things.’ Bayer’s potting at scale came to its peak in 2004 with a series of extremely large vessels made for an exhibition. The show was an unmitigated disaster: a second, simultaneous, display in a separate venue drew all attention away from his exhibits. There were no staff to watch over the pots, and vandals broke in twice to push them off their plinths. Bayer’s insurance pay-outs were the only recorded sales of the show.

Huge, monumental jars by Svend Bayer, among the largest he has ever made. All were thrown, coiled, and paddled by hand and wood-fired in Bayer's anagama kiln.

The series returned instead to Bayer’s garden at Duckpool, where they became a permanent feature; they now stand as a monumental record of a time in his career, the last really big pots he ever made. All will be on display at Goldmark for the opening of Bayer’s March 2020 exhibition.

Huge jars by Svend Bayer

Joining them is a very special selection of work. These will be the first pots by Bayer we have received in eight years, the very best pots put aside from three years of firing at Kigbeare – an ‘embarrassment’, Bayer calls them, with typical humility; a word I’ve only ever heard used collectively of riches. I will leave the task of discussing their finer details to David Whiting, who is set to author what will be our 47th pottery monograph. But my impression from the work I have seen so far, and what I thought unthinkable as I walked around that exceptional 2012 exhibition, is that Bayer has surpassed himself.

Much wood-fired work is all surface; an encrustation of glass lobes and delirious rivers of ash. But in Bayer’s pots, you never feel overwhelmed by the extraordinary effects of his kiln, the intense violence inflicted on large vases and vessels in the firebox. ‘No amount of wood firing will help a bad shape’, he has said in the past; it was his sense of form, his prowess on the wheel, that prompted Cardew to describe him as a ‘force of nature’, and form is forever at the forefront of his mind.

I can think only that these new pots are like planets. That in their swirls of wood ash, seas of celadon blue and green, scallop shell skeletons raised like white cliffs from the foam, they are like living globes of constellatory importance. My fingers are drawn over them by their tips like ships looking for safe passage to new and distant lands. As I did eight years ago, I feel I have arrived again.