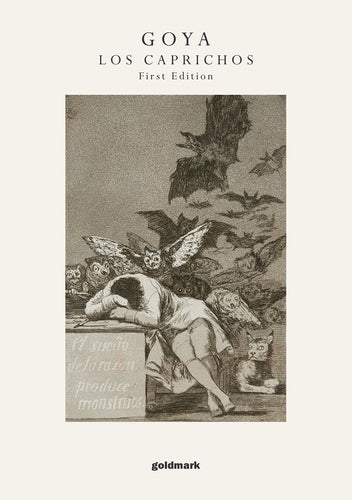

The rarest of Francisco de Goya Los Caprichos etchings; first edition, 1799, handled by the great man himself. Gallery artist, Jenny Grevatte, on painting trees. Stoneware pots by Jim Malone, widely acknowledged to be one of the finest potters working in Britain today.

Francisco de Goya - Los Caprichos

The publication of Los Caprichos marked a defining point in Goya’s career. In 1792 he developed a debilitating illness – exactly what he suffered from, no one knows – which would ultimately leave him deaf. His recuperation took over five years, during which the isolation imposed by his withdrawal and his deteriorating hearing had a profound impact on his life. He quickly became depressed – cut off from the world, quite literally, by his deafness – and feared for his sanity.The Caprichos were not just a tour-de-force of satire: they were a suite of technical mastery too. Before their publication, the last apotheosis in the etching medium had been achieved by Rembrandt. In Rembrandt’s time, the process was still relatively straightforward: a metal plate – usually copper – is covered in a thin ‘ground’ of waxy resin which is then smoked over a flame, the soot turning the surface of the wax black. This makes it easier for the etcher to see his design, which he makes by drawing into the resin with an etcher’s needle. Where he draws, the copper under his line is laid bare.The plate is then submerged in a bath of acid, where the mordant ‘bites’ the exposed lines in the copper plate. These bitten grooves will hold ink when the plate is cleaned of the ground and prepared, and the impression can be taken on a rolling press. Large areas of darkness could only be achieved through very close, dense cross-hatched lines that gave an impression of uniform blackness, but by the time Goya came to print the Caprichos a recent technological advance was available to him which allowed gradations of tone comparable to a watercolour wash.This technique was called aquatint: it involved dusting fine particles of resin onto the plate, which was then heated, causing the resin to melt into a minutely pock-marked ground. Goya and his technicians were among the first in Spain to make use of it, and the results were astonishing. Figures emerge from near total blackness, lurk in the shadows, leer out in contrasts of linear sharpness and aquatint haze; at least two prints were composed wholly through aquatint, blocking out and rebiting the plates over and over again until the composition was complete – an extraordinary feat of technical printmaking.The process would become essential to the Caprichos’ theme: Goya’s host of goblins and ghouls are creatures of the night, belonging properly to the world of dreams; aquatint plunged the series into a twilight wash of sepia. These images from a first edition set, known to have been one of the first thirty or so copies that Goya had bound, reveal the sumptuous levels of depth and perspective this new skill afforded him.The term ‘caprice’ is normally redolent of fantasy and whimsical fancy, but Goya’s are as nightmarish as they come. The final, apocalyptic plate of the series – Ya Es Hora(‘It is time’) – calls the heady nocturne to its end, as witches, phantoms and howling devil-priests retreat into the night with the arrival of dawn and the ‘waking’ of Goya’s dream vision. In its savage jabbings at the moral depravity of Spanish society, its journalistic exposé of cultures of corruption and stupidity, it anticipated the modernist vigour of Dada and the wartime anger of the Expressionists, of Ernst, Grosz and Dix. To know that it was a failure on its release only reaffirms its extraordinary modern-day status as a masterpiece of near unrivalled technical and satirical expression.Jenny Grevatte

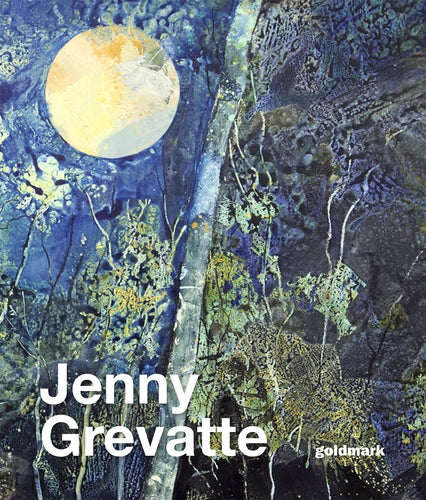

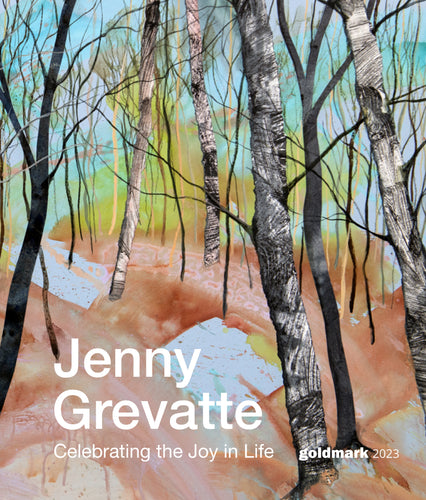

Grevatte’s painting processes range from the methodical to the playful. Most of her paintings are dubbed ‘mixed media’, and for good reason. Many have laboriously layered surfaces built up from collaged elements or broad painted strokes, the overlapping patches of dark and bright colour echoing intersecting branches and the dance of light between leaves. Splatter painting adds to her trees a convincing polychromy: look closely at the surface of an old oak or thorny hedgerow and you’ll find any number of reds and greens, rusts and lilacs in the spotted surfaces of the wood. Dribbling wet paint onto paper from a brush or pipette, random pools and droplets can be manoeuvred through the use of a straw, creating coloured streaks that catch the light.Her dedication to exploring new avenues of paint application, of collage, grattage, sgraffito and splatter, demonstrate her awareness of the particular qualities of each new painted experience. Each new tree painting is not merely generic; it speaks to a specific experience, and to specific subjects. A series of paintings of oak trees are not termed ‘studies’ but ‘portraits’; each example is as multifaceted as a human figure. To treat them as Grevatte does, with as much expressive and sympathetic depth, reaffirms our peculiar relationship with trees, onto which we seem to project so many reflections of our own inner psyche.Jim Malone

Jim Malone was born in Sheffield in 1946. After the death of his father, his mother moved the family back to her native Wales. Malone went to train as a teacher in Bangor in 1966 and then accepted a teaching post at a school in Essex in 1969. He continued with his childhood love of drawing and after 3 years of teaching had a portfolio substantial enough to gain him a place at Camberwell School of Art.He is a sociable and friendly man but chooses to work in isolation; pottery is not just his job it is his way of life. Malone’s pots, be they his flaring bowls, decorated with hakame and iron brushwork, Korean style bottles or his jugs (regarded by many as the best in Britain), all show why he is one of the foremost potters working in the UK today.His two chambered oriental climbing kiln finishes what he starts with his throwing and glazing. Striking combinations of Tenmoku jars and slab bottles with brilliant blue/green copper pours, elegant bottles with perfectly proportioned necks finished with a rich olive Nuka and yunomi and teabowls – ashed and incised or ridged and stamped, all display the natural unforced beauty distinctive not only of Malone’s pots, but also the landscape in which he makes them.Malone has had articles published in Pottery Quarterly and Ceramic Review and has exhibited widely throughout the UK and USA. His pots can be found in the collections of the V&A; Ulster Museum, Ireland; Manchester Metropolitan University; Liverpool Museum and Art Gallery to name but a few.